Crop Production

Learn the biology, signs, and symptoms of these insect pests along with the current best practices for monitoring and managing infestations.

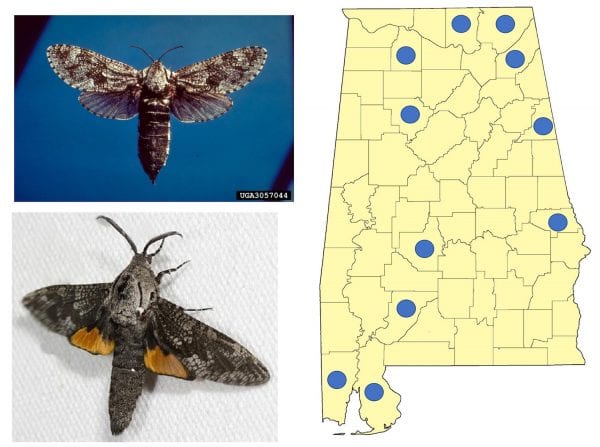

Carpenterworms are moth larvae that tunnel into hardwood tree species in landscapes and nurseries. Two species of carpenterworms (Prionoxystus spp.) are native to the United States. In Alabama, Prionoxystus robiniae (carpenterworm moth) is the most common. These moths are not widely captured in Alabama but are thought to occur in almost every county (figure 1).

The larvae are the damaging life stage and can cause significant losses in hardwood timber stands and production nurseries. The larvae live within the xylem tissue, and symptoms of infestation vary among tree species. Because of this, growers may not recognize that they have a carpenterworm infestation and instead attribute the damage to other problems (disease, other insects, or environmental factors).

The Carpenterworm Life Cycle

Figure 1. Carpenterworm female moth (left upper) and male moth (left lower). (Photo credits: female moth, James Solomon, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org; male moth, Nolie Schneider, North American Moth Photographers Group)

Carpenterworm moths are large (1 1⁄2 to 2 inches in length) with a gray and white mottled appearance and about a 3-inch wing span. The males and females are similar in size and body coloration. The difference is that males have a small orange patch on the hindwing (posterior set of wings) and larger, plumose antennae (figure 1).

The female moth produces a pheromone that attracts males for mating. Mating is necessary for a female to produce viable eggs. The eggs are deposited on the bark of common hardwood tree species such as oak, maple, ash, poplar, birch, stone fruit trees, and willow. In Alabama nurseries, oaks are the most common trees attacked by carpenterworms.

Females deposit most of their eggs in the afternoon to evening within 1 to 2 days of emerging from trees. Female moths in the same insect family select trees for egg laying based on bark characteristics, but these characteristics are not known for carpenterworm moths.

Eggs are deposited singly on trees and hatch in 2 to 3 weeks. Newly hatched caterpillars (larvae) bore into the tree, making a tunnel (gallery) as they feed on the wood. Nursery trees, perhaps due to their smaller caliper, typically can support one or two larvae per tree. Larger trees may have dozens of larvae per tree.

The insects move through the outer sapwood layer then turn and move into the inner heartwood, running almost parallel with the trunk. It is unlikely that carpenterworm larvae will be observed once inside the tree.

Since oak trees host a range of insect borers, it is important to differentiate between carpenterworm larvae and roundheaded and flatheaded borers. Flat- and roundheaded borers are legless, but carpenterworms have three pairs of legs on the segments behind the head. For more information on borer pests, see “Borer Pests of Woody Ornamental Plants,” (Extension publication ANR-2472).

Figure 2. Swollen area of tree indicates where a carpenterworm moth emerged

For unknown reasons, caterpillars take 1 year to complete development in certain trees or locations. In some places, they may take 2 years to complete their life cycle. Larvae pupate in the spring near the gallery entrance and remain there for 3 to 4 weeks before emerging. When the adult moths emerge, they leave behind the pupal case protruding from the gallery (figure 2). Adult moths can emerge from late March to early April in Alabama, with the flight period and mating period ending in June.

Because pupation and adult emergence are temperature dependent, plant phenology may be more useful than calendar dates in predicting moth activity. In the forest, the first capture of moths typically coincides with full bloom of the flowering dogwood (Cornus florida). However, emergence from trees in the nursery occurs later in the season once the first moths have been captured in traps. The appearance of pupal skins on nursery trees is coincident with full bloom of the southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora).

Signs and Symptoms of Infestation

Damage to nursery trees, particularly nuttall (Quercus texana) and willow (Q. phellos) oaks, occurs as the larvae feed inside the tree. The tree responds to this feeding by forming a swollen or knot-like area near the areas where the gallery opens to the outside. Often the tree does not show any visible signs of attack in the canopy or foliage.

The oak tree in figure 2 has a healthy-looking canopy. Upon closer inspection, however, a swollen area on the stem is visible. Each swollen area has an associated hole (the entrance to the gallery) that is usually in a sunken area of the bark. The gallery entrance may be oozing and discolored from brownish frass (carpenterworm excrement) being expelled from the entrance of the gallery. These swellings may compromise the strength of the tree trunk or be a defect that causes a producer or buyer to reject a tree.

The appearance of the pupal case protruding from these swollen areas occurs in spring. Unfortunately, this indicates that the carpenterworm damage is already complete. Trees with this type of damage generally will not recover, and any insecticide applications would not be recommended.

Monitoring for Infestation

Figure 3. A typical trap used to monitor for different types of moths. The top is solid and the bottom is sticky to trap moths. The small red capsule-like piece contains specific sex pheromones to trap male carpenterworm moths.

Because most infested trees are asymptomatic, other methods to monitor carpenterworms are recommended. One is to exploit their attraction to pheromones. A synthetic version of the sex pheromone is commercially available and can be added as a lure to sticky traps to monitor the activity of male moths (figure 3).

In field trial studies, one trap baited with pheromones is used per tree block (about 300 trees). The disadvantage of using pheromones is that they only indicate male moth activity and not the activity of females. Traps with pheromone should be place in the field in spring before flowering (Florida) dogwood begins to bloom.

Another method of detection is to examine trees for the swollen areas in the spring and fall. If a tree has an active borer, a pupal skin will be obvious about the time southern magnolias are in bloom (spring). Trunk damage in the fall is also apparent in October or November. This damage likely results from new larvae that entered the tree that same year (spring).

Management Options

Chemical Control

Surveys of Alabama nurseries indicate that 5 to 15 percent of nontreated oak trees in a block could be infested with carpenterworms. Management of carpenterworms and other insect borers is focused on controlling the insect before it enters the tree by using insecticide applications to the trunk.

Several trunk spray programs have been evaluated in which insecticides were applied every 2 weeks from March to May. These studies showed that applications every 2 weeks resulted in less damage than applications of the same insecticide applied every 4 weeks. However, these spray programs are not always successful at eliminating all attacks. Treated trees have fewer attacks (0 to 4 percent of trees attacked) with trunk sprays made biweekly from March through May.

The limited success of insecticide sprays may be due to the multiyear development of carpenterworms. For example, because of their 1- or 2-year life cycles, treatments in spring may prevent new attacks but may not kill nearly full-grown larvae already in the trees.

Elimination of Culled Trees

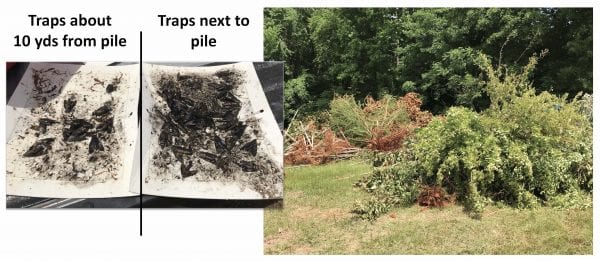

Figure 4. Dead or unmarketable trees piled in the nursery can be a source of new carpenterworm moths.

Management of infested trees left in the field can be an important action to reduce carpenterworm abundance. Some nurseries will push the unsellable trees into a pile, which can then become a source of developing carpenterworm larvae and moths (figure 4).

Since these borers consume wood, infested trees in or out of the ground can support insect development. Moths that emerge from these culled trees can fly back into the nursery block and lay eggs on the next crop restarting their life cycle. Culled trees should therefore be burned, chipped, or buried that same year to prevent continued development and emergence of new carpenterworms.

Cover Crops

Early U.S. Forest Service publications suggest that tall vegetation growing around the trunk of forest trees will reduce or prevent attacks from carpenterworms. Research in Tennessee has applied this cover crop approach to the management of other wood borers. When used, cover crops can reduce attacks from flatheaded borers (beetles) in maple trees equivalent to the use of an insecticide.

The downside to cover crops is that they compete with the trees for water and nutrients and can significantly reduce trunk diameter and canopy size relative to trees in clean rows. This effect is not replicated with the use of tree guards.

Cover crops may help to reduce or eliminate attacks from carpenterworms, but nurseries need to consider the extra production time and costs due to delayed growth. The reduced growth in the Tennessee research study was worst in the first year and less in the second year.

Mating Disruption

Research with related moths indicates that mating disruption may reduce infestations from this insect. Mating disruption is a different application of the same sex pheromones used in monitoring. This approach overexposes males to the pheromone, thereby reducing the chance that they will find females. If the females cannot mate, they cannot produce viable eggs or larvae.

Lures without traps are typically hung in about 10 to 25 percent of the trees in the block. From the same research mentioned previously where mating disruption was used, less than one active gallery per tree was found in the first year and less than half that in the second year. There were about two galleries per tree on average in trees left unprotected.

If used for carpenterworms in nursery trees, mating disruption would begin when the first moth is captured in a pheromone trap, and the pheromone lures would be replaced monthly through the end of June (about 3 to 4 months). This tool is used to reduce the number of fertile female moths in the nursery but should not be considered a complete replacement for monitoring or chemical controls.

David Held, Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology, Auburn University, and Jeremy Pickens, Extension Specialist, Nursery, Greenhouse, and Horticulture, Auburn University

David Held, Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology, Auburn University, and Jeremy Pickens, Extension Specialist, Nursery, Greenhouse, and Horticulture, Auburn University

Reviewed August 2023, Carpenterworms in Nursery Trees, ANR-2786