Forestry

Figure 1. Landowners often overlook the option of uneven-aged management of longleaf pine because they think it is too complicated.

Longleaf pine’s life history is unique among southern pines. It was once the dominant species on the southeastern coastal plain from North Carolina south through central Florida and west to eastern Texas. The location of historic longleaf forests was tied closely to the occurrence of frequent fires that were once common across the Southeast. Because of these fires, longleaf pine forests were generally open with very few woody stems in the midstory, and they had understories that consisted of grasses and legumes. This led to longleaf forests often being called “longleaf savannas.”

The area covered by natural longleaf forests has been declining for 150 years. This is due, in part, to conversion to agricultural use, urban development, lack of fire (natural or human caused), and plantation forestry. Widespread harvesting of forests in the late 1800s reduced longleaf acres substantially. Natural regeneration of longleaf at the time was also generally unsuccessful. To germinate, longleaf seeds benefit from contact with bare soil, but fire suppression allows hardwood and other pine species, such as loblolly, to invade the remaining stands of longleaf, thus inhibiting regeneration.

The original longleaf pine forest was self-perpetuating where seedlings always had to be present in the understory. Longleaf pine seed is heavy and falls only about 75 feet from the parent tree. So stands of young seedlings needed to develop under larger trees, where they would wait for an opening in the canopy to occur so height growth could begin in earnest. These openings would have varied in size and may have ranged from less than an acre, due to the loss of a single tree from a lightning strike or windfall, to a few acres due to insects or a large-scale wind event. In some cases, there were also large openings of several hundred acres due to tornadoes or hurricanes. Regardless of the opening size, seedlings always had to be present on the ground for the forest to continue.

Today, when landowners consider restoring longleaf pine on the landscape, most think they need to clear-cut and replant to start the next forest. While artificial regeneration methods such as planting are common forestry management practices, it is not the only way to regenerate your forests. Planting can be expensive and getting seedlings to survive can sometimes be difficult. Of course, if you do not have any longleaf pines in your forest but want to manage for them, then you will have to consider some form of artificial regeneration like planting. But if you are lucky enough to have longleaf pines already on your property, you have the potential to naturally regenerate your forest even if it is a plantation.

One often overlooked way to regenerate longleaf is through the use of an uneven-aged method, which is one way longleaf forests regenerate. Landowners often hesitate to consider uneven-aged management as an option for their forest, because they think it is too complicated or they just do not know how to get started. This publication explains uneven-aged silviculture and how it can be applied in the management of longleaf pine. It will also help you decide if it is right for you and your property.

How does an uneven-aged stand compare to an even-aged one?

Before European settlement, longleaf naturally occurred in either even-aged or uneven-aged stands. The major difference is based on the size of the disturbances that created them. Uneven-aged stands, or forests with trees of many ages, are formed when individual or small groups of trees naturally die from intense fire, wind, insects, and lightning strikes. As individual trees die, they create gaps in the canopy. These gaps allow seedlings on the forest floor to receive the light that they need to begin growing.

Natural even-aged stands are made up of trees that all started growing within a few years of each other, a bit like a pine plantation. These forests were formed by the removal of overstory trees through large-scale disturbances such as hurricanes or tornadoes. These disturbances formed larger areas where forest canopy was removed and, as a result, provided open space for longleaf regeneration that was already established to grow. This led to large areas of trees that were similar in age.

Why not plantation style management for longleaf?

As mentioned earlier, one reason you may want to consider uneven-aged management and natural regeneration is the cost. Costs of planting longleaf are typically higher than the costs associated with planting other tree species such as loblolly. For example, in 2012 it cost around $90 per acre to plant containerized longleaf seedlings compared to $55 per acre to plant bare-root loblolly pine seedlings. Because of the difference in cost of planting and longer rotation length for longleaf, it may be difficult to justify continuing a longleaf plantation for more than one rotation. Longleaf’s ability to naturally regenerate in forest gaps provides you with the chance to reestablish your stand without removing all the trees in a forest. This eliminates the cost of planting by using the seeds that your trees naturally produce as the source for your future forest.

Figure 2. When a single tree dies in the forest, like the one pictured here, it opens the forest canopy and allows light to reach the forest floor. When it does, understory seedlings have the opportunity to grow in its place.

Another benefit of using uneven-aged management is that you also have the opportunity for regular income from your forest. When your trees become large enough to profitably harvest, you can establish a cutting schedule that will allow you to make periodic harvests in perpetuity. This sustainable process can allow for income every 7 to 12 years depending on what cutting cycle your forester selects. Alternately, in pine plantation management, the stand is usually clear-cut after one to three thinnings. The next forest must then be allowed to grow to a merchantable size from seedlings before it can be thinned again for a profit, a process that can take as long as 15 years.

What should I consider when converting my forest to an uneven-aged system?

Because of its unique characteristics, longleaf pine can sometimes be considered difficult to manage. Keeping the following in mind can help you make uneven-aged management fairly straightforward in the long run.

First, it is important to remember that before you can successfully regenerate longleaf pine naturally, you must prepare the site to control the understory and optimize seed catch and germination of seedlings. Depending on the condition of your forest, site preparation may need to take place several months to several years before thinning the overstory. Forests that have been fire excluded for some time can have a heavy litter layer and dense brush in the understory. These conditions are not conducive to natural regeneration of longleaf and will take more time to prepare than those that have been actively managed with fire and have more open, grassy understories. However, you have several tools at your disposal to get your forest ready. These include a forest inventory, prescribed fire, herbicides, and understory mulching.

Forest Inventory

A forest inventory is the assessment of the amount, age, and distribution of timber and other forest resources on your property. Through a forest inventory, you can get an idea of how large your timber is, where it is located on the landscape, and its value. This assessment can also provide information on the understory condition of your forest. Combined, this information can help you make educated management decisions. A forest inventory is best completed by a professional forester. Alabama Extension’s publication, ANR-1365, “Landowners and Forest Inventories: Frequently Asked Questions,” provides more information on forest inventories and how they are used.

Prescribed Fire

Fire is the least expensive and preferred method for managing the understory to prepare the forest floor for optimum longleaf pine seed catch. Without fire, hardwoods and other pines outcompete and limit regeneration of longleaf. To use fire effectively, it is important to consider (1) the vegetative composition of your forest understory and (2) your forest’s physiographic location. These two factors help determine the season (month) in which you should burn and how often you might need to burn. Sites that have not been maintained with frequent fire may need additional treatments such as herbicides or understory mulching before you attempt natural regeneration. Always consult a prescribed fire expert and your local forestry commission before implementing a prescribed fire.

Figure 3. Regenerating longleaf pine naturally requires preparing the site to control understory.

Herbicides

When the understory becomes overgrown, a herbicide treatment may be the quickest method of initial control. Chemical control of understory plants is sometimes needed when they compete with young seedlings for resources, such as light, water, and nutrients. This method can be used alone or to enhance the effects of prescribed fire or mechanical understory mulching. Several herbicides are licensed for forestry use, but determining which one is right for your forest will depend on the species you are targeting, soil type, climate, and region. Herbicides require careful selection and application by a professional, so consult a natural resource technical service provider or certified chemical applicator to help you with any forest herbicide treatment.

Understory Mulching

Understory mulching is a land management technique often used with herbicides and prescribed fire in forests that have been fire excluded for extended periods of time. Mulching can quickly reduce dense understory vegetation and small midstory trees that cannot easily be killed or controlled using prescribed fire alone. As with any site preparation method, understory mulching should be done at least 6 months to a year before you want to begin the regeneration process. This is needed because mulching can leave a deep mat of wood chips on the forest floor that can take time to decay. A follow-up herbicide treatment during the growing season before seed fall is also recommended to treat stump sprouts. Understory mulching can be expensive, but it is a useful tool in areas of dense understory growth or on smaller stands where prescribed fire is not an option.

How can I create an uneven-aged forest on my property?

When you have some idea of the species, size, and distribution of overstory trees based on a forest inventory and your understory is well managed so that seedlings can become established, you can start the process of managing overstory trees for an uneven-aged forest. To do this, land managers and landowners mimic natural forest gap–dynamics processes with active forest management practices of single tree or group selection harvests.

Single Tree Selection

Single tree selection is practiced when individual trees are removed from across the stand without making large gaps in the canopy. This process is similar to the loss of individual trees due to natural processes such as insects or lightning.

To implement in a longleaf pine forest, the stand is often thinned to approximately 40 to 50 square feet of basal area. (For more information on basal area and how to calculate it, see Alabama Extension publication ANR-1371, “Basal Area: A Measure for Management.”) This stocking level is recommended because it opens up the forest just enough to allow light and other resources for new seedlings to become established under parent trees. It also provides enough canopy cover to produce needle fall that helps carry prescribed fire across the forest. This process keeps your forest from having large gaps in the canopy, therefore, also limiting the space for regeneration of undesired species, such as sweetgum, that need a lot of light to survive.

When selecting trees to thin, low-value cull trees should be selected first. Then, any other smaller or lower quality trees should be chosen, leaving the larger cone-bearing trees standing. This will keep the stand from being “high-graded” or stripped of all high-value trees and provide a seed source for regeneration. Single tree selection can also be used to enlarge pre-existing gaps by removing trees around the edges to enlarge areas of older regeneration.

When seedlings are well established in these openings, additional mature trees can be removed to allow seedlings to continue to grow. Fire should be limited on the site the following spring when new seedlings are becoming established. If the site has been well maintained with fire and seedling survival is satisfactory, a follow-up fire frequency of 1 to 3 years may be appropriate. Follow-up treatments with fire help prevent brown-spot needle blight on young seedlings and also keep woody competition in check.

Group SelectionIn contrast to single tree selection, group selection harvests remove small groups of mature trees across the forest. This creates larger gaps in the forest canopy and allows space for desired and undesired species. Gaps should not be so large that there is the possibility that the center is more than 75 feet from parent trees. In this system, it is especially important to monitor your forest to be sure that your understory is well prepared to receive the seed and that trees are producing seed prior to conducting the initial harvest.

Just as with a single tree selection, fire is an important component of the system. Monitor gaps to be sure that fire is carrying through them and controlling competition. If not, hardwoods can become established that are then difficult to manage with prescribed fire, and natural regeneration of longleaf can suffer.

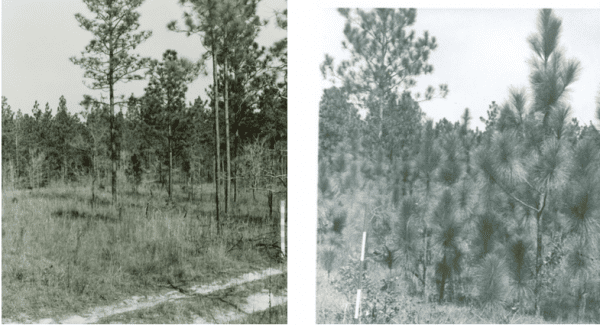

Figure 4. Farm 40 on the Escambia Experimental Forest near Brewton, Alabama, in 1952 (left) and in 1962 (right). These pictures were taken from the same spot; note range poles. The picture on the left shows how longleaf will seed into gaps in the canopy and how seedlings in the grass stage can respond when the overstory is removed. (Photo credit: USDA Forest Service, Escambia Experimental Forest Archives)

Figure 5. And this is the same forest today! Uneven-aged management of longleaf pine allows landowners to generate timber revenue from their forest approximately every 7 to 12 years because mature timber is always present. (Photo credit: John Kush)

How does an uneven-aged longleaf pine stand benefit wildlife?

Different wildlife species require different habitat structures. Uneven-aged management provides many different types of habitat in one forest at the same time. With variations across a stand, these patches of regeneration provide a variety of forest structures suited to a diversity of wildlife species, both game and nongame. Over the life of the forest, uneven-aged stands have potential for higher wildlife diversity than single age stands. This is achieved by having trees of various sizes across the landscape.

Bobwhite quail, which requires an open, grassy understory for nesting, foraging, and raising young, benefit from uneven-aged forests. Because of the need to burn frequently, uneven-aged longleaf stands should provide good nesting habitat. Many of the species of grasses, forbs, and legumes that quail need for food and cover thrive when fire is applied every few years. If the understory is not burned or disturbed for several years, the land begins to lose its ability to support quail.

Other species benefit from this forest type too. Gopher tortoises are an important keystone species because other species, such as indigo snakes and many small mammals, use their burrows. Gopher tortoises require sandy soils that are easy to dig in, and longleaf is one of the few southern pines that will grow well on these soils. Game species such as white-tailed deer and eastern wild turkey can also be found here. White-tailed deer benefit from the production of native understory for food and cover. The open understory provides space needed for turkey poults to move about easily. Bugging opportunities are also abundant in these areas. By promoting good conditions for longleaf regeneration, you will also be providing optimal habitat for many wildlife species too.

How can an uneven-aged longleaf pine stand benefit me?

For many landowners, scenic beauty is an important aspect of forest ownership. With uneven-aged management you do not clearcut to regenerate, the aesthetics of your forest are enhanced, and you have more opportunities for recreation, hunting, and wildlife viewing. While there is nothing inherently wrong with a clearcut, an uneven-aged forest will allow landowners who prefer to keep a mix of ages and sizes of trees on their forest while still receiving regular income from timber harvesting. As an added benefit, an uneven-aged management system can also help minimize soil erosion and increased runoff that can happen in the first years after a clearcut. This can help protect the productivity of your property.

Managing longleaf in uneven-aged stands also allows for the landowner to generate timber revenue more often than is possible with even-aged management. Because you do not remove all the mature pines off of your stand, you should be able to harvest a mix of timber sizes from your forest every 7 to 12 years. This is beneficial because the rotation length for longleaf can be from 35 to 90 years depending on the site. In addition to opportunities for more frequent income from harvesting, landowners also have the chance to harvest mature timber more often, which will bring you more money per ton of timber sold compared to smaller diameter trees.

Because frequent prescribed fires and good understory management result in little woody debris on the ground, many longleaf forests are also managed for pine straw production. As the popularity of pine straw as landscaping mulch increases, there will be a higher demand for longleaf pine straw, which is considered higher quality than straw from other pine species. This means that you could continue to rake pine straw from patches of regeneration that should always be present in your forest. This is another opportunity for regular income from your forest. In some cases landowners can make as much as $100 an acre per year from pine straw production alone. For more information on pine straw production see Extension publication ANR-1418, “Harvesting Pine Straw for Profit: Questions Landowners Should Ask Themselves.”

Figure 6. Landowners looking for more than just timber revenues may benefit from uneven-aged management of longleaf pine.

Conclusion

The ability to retain canopy cover over large portions of the stand while still harvesting timber make uneven-aged management ideal for landowners who want to use their forest lands for multiple uses. This management system allows landowners to generate revenue from activities such as hunting leases and pine straw production while also being able to remove larger, higher value trees during each harvest. These harvests will create the openings that longleaf seedlings require to survive and grow. Fire needs be a part of this management scheme so that the understory stays clear of woody stemmed plants that will outcompete longleaf seedlings and affect wildlife habitat. Fire also helps promote the health and growth of longleaf seedlings.

Uneven-aged management of longleaf pine may be a good strategy for landowners that are looking for more than just timber revenues. Many people now consider forest aesthetics and wildlife management as or more important than maximizing timber revenue. If this management style interests you, please contact your county Extension agent, county forester, or a consulting forester who specializes in this type of management to find out more about this often overlooked management opportunity.

Figure 7. Group selection harvests remove small groups of mature trees across the forest. This creates gaps in the forest canopy and allows for regeneration of longleaf pine.