Food Safety

News reports on recalls from retail stores and foodborne outbreaks related to contaminated food have increased in recent years. Consumers are often confused by the terms “food recalls” and “foodborne outbreaks” because they are commonly reported at the same time.

Health officials generally issue both warnings, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These warnings alert the population to certain risks, such as cases of Listeria monocytogenes infections related to ice cream, hepatitis A linked to fresh strawberries, salmonellosis connected to peanut butter, and the Cronobacter infection related to infant formula.

Figure 1. Various products can be related to foodborne outbreaks.

To understand the differences between food recalls and foodborne outbreaks, consumers need to know why a product is recalled or involved in an outbreak.

Health hazards, including biological (bacteria, virus, parasites), physical (plastic pieces, metals, glasses), and chemical (sanitizers, cleaners, fertilizers), can be introduced to food products at any point in the food supply chain. Allergens such as peanut, egg, milk, soy, and shellfish are also considered health hazards that can cause life-threatening reactions and are commonly associated with food recalls. When people consume contaminated food, they get sick and an outbreak begins. This may even lead to a recall of the specific product leading to the illness.

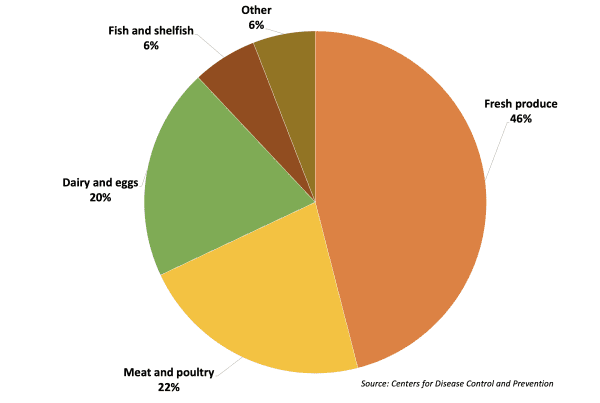

The primary cause of foodborne outbreaks in the United States is Salmonella. Fresh produce is the number one product of contamination, accounting for nearly half of foodborne outbreaks yearly.

What Is the Difference Between a Recall and an Outbreak?

Figure 2. Foodborne outbreaks of fresh produce account for nearly half of all foodborne outbreaks in the United States.

The answer is simple: foodborne outbreaks occur when two or more people from different households get sick by eating the same contaminated food or beverage. A food recall is the removal of contaminated products from the market because of a health risk. However, it is not true that all outbreaks will lead to recalls or that all recalls will lead to foodborne outbreaks. Circumstances can be very specific depending on each situation. A product recall usually follows a foodborne outbreak, but the opposite may not be true. Sometimes, the source of a foodborne outbreak is identified only after a product has expired and been removed from the shelves; consequently, it does not require a recall. Some recalls might happen before the product is available to consumers and when authorities can identify the contamination before an outbreak occurs. In other cases, a product recall is not issued because the outbreak source has never been identified, which could lead to more illnesses.

How Do Public Health Agencies Respond to Outbreaks?

Usually, when an outbreak is identified, public health agencies, including the Alabama State Department of Public Health, the FDA, and the CDC, quickly initiate an investigation. These agencies collect as much information as possible to determine the source of the outbreak and prevent future illnesses. During the investigation, these agencies issue an investigation notice to alert consumers of an ongoing foodborne outbreak not yet linked to a food source. Once the source has been identified, public health authorities issue a public health alert to provide urgent and specific advice to consumers and retailers with details about the product name and specific lot numbers. For more detailed information regarding foodborne outbreak notices, visit the CDC website.

When Should Consumers Take Action When a Recall or Outbreak Is Declared?

Consumers should be aware of the terms “recalls” and “foodborne outbreaks” so they can take action to prevent illness. Consumers should wait for more information when an outbreak is ongoing, but the source has not yet been identified. However, consumers can take action when the source and product are identified. If consumers have a specific food product at home, they should discontinue its use and discard it to avoid illness, while retail stores should immediately stop selling the product. Most grocery and wholesale stores and even the company producing the food give refunds to consumers if they have purchased the specific product. Consumers should look for the specific “lot code numbers” or “best if used by” on the recalled product label to see if they have the food at home. Information about recalled products is available in the outbreak investigation report issued by the FDA. Visit the CDC website for examples of outbreak investigations with recommendations for consumers, retailers, repackers, and manufacturers regarding the recalled food.

What Are the Symptoms of Foodborne Illnesses?

Figure 3. Wash hands for at least 20 seconds before handling food.

Foodborne illnesses are caused by various microorganisms, including E. coli, Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, norovirus, Vibrio bacteria, Cyclospora, and many others that can cause mild to severe symptoms. The severity of the illness will depend on the individual’s health, the amount of contaminated food consumed, and the type of microorganism causing the illness. Also, symptoms might take hours to days to occur.

Anyone can get sick with a foodborne illness. However, certain groups of individuals are more susceptible to getting ill or having health complications, including adults over 65 years, children younger than 5 years, individuals who are immunocompromised (people with certain illnesses including HIV/AIDS, cancer, autoimmune diseases), and pregnant women. These individuals need to take additional steps to prevent food poisoning by learning about the most common foods associated with foodborne illnesses. Learn more about food-linked illness on the CDC website.

Foodborne Illness Reporting and Prevention

Figure 4. Clean countertops and food contact surfaces before and after handling food.

An outbreak investigation relies on self-reported data from sick individuals; thus, the estimated number of cases related to a specific foodborne outbreak can be significantly higher than reported. Regulatory agencies and officials constantly update their guidelines and regulatory requirements to minimize food safety risks and prevent future foodborne outbreaks. Advances in screening tools continue to improve clinical diagnostics and surveillance. However, the key to reducing foodborne outbreaks and food recalls is prevention. Implementing food safety practices and following regulatory requirements and recommendations are essential to reducing food safety risks in the food supply chain. At home, consumers should wash their hands for at least 20 seconds before handling food; properly cook meats and eggs; separate raw meat, seafood, and egg from other foods; and clean food contact surfaces and countertops before and after handling food.

The FDA and the CDC maintain an updated list of the outbreak and adverse event investigations, so consumers and health professionals can know the current information about foodborne outbreaks and food recalls. Consumers who have symptoms of foodborne illnesses should contact their health care provider to seek medical assistance. Consumers can also contact their local health department to report a potential foodborne illness. Consumers who want to report a complaint or adverse event related to a specific food product should contact the FDA via phone, online, or mail.

Additional Resources

- “Investigations of Foodborne Illness Outbreaks”

- “List of Selected Multistate Foodborne Outbreak Investigations”

- “How to Report a Foodborne Illness – General Public”

- “Consumer Complaint Coordinators”

Camila Rodrigues, Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor, and Kristin Woods, Regional Extension Agent, both in Food Safety and Quality, Auburn University

Camila Rodrigues, Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor, and Kristin Woods, Regional Extension Agent, both in Food Safety and Quality, Auburn University

New July 2022, Food Recalls and Foodborne Outbreaks: What’s the Difference?, FCS-2703