Fish & Water

Rainscaping your landscape can reduce polluted runoff that endangers vulnerable water bodies that are downstream from your property. Learn measures you can take to enhance your landscape and protect critical water supplies.

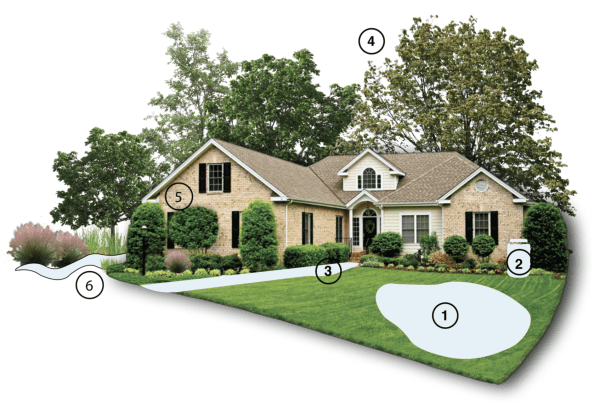

Figure 1. Rainscaping helps prevent polluted runoff from reaching local water bodies. (1) Rain gardens can help capture stormwater runoff, (2) rain barrels can help store water for later release into the landscape, (3) permeable pavement can help water infiltrate into the ground, (4) trees and vegetation help reduce runoff, (5) turf management and turf planting alternatives reduce runoff, and (6) vegetated buffers along streams provide for wildlife habitat and protect the stream bank.

Rain that falls on your yard does not necessarily stay in your yard. Some water infiltrates into the ground, while some is taken up through plant roots and released back into the air via transpiration. Other water, however, can run off the landscape and flow into a roadside ditch or storm sewer, where it is redirected into local creeks and streams. This runoff can pick up soil particles, motor oil, fertilizers, nutrients, or other pollutants on your property and carry them downstream, where they can cause water-quality problems.

Rainscaping is the use of sustainable landscape design and management practices that help to prevent polluted runoff from reaching local water bodies. It may include

a combination of plantings, water features, catch basins, permeable pavement, rain gardens, or other measures to keep stormwater where it falls (figure 1). This approach encourages homeowners to think beyond a standard turf yard to how plantings can serve both an aesthetic and practical function.

If much of your yard is impervious (roofs, driveway, sidewalks) or covered in turf, rain will run off your property, causing more water to enter the storm drain system (figure 2). To keep the runoff as clean as possible, minimize impervious surfaces and bare soil, and keep the runoff away from chemicals. Opt for a diverse landscape that reduces turf and uses more trees, rain gardens, shrubs, perennials, mulch, and amended soils to intercept and disperse rain as it falls; this will allow more water absorption into the soil and by plants.

Following are five practices you can implement to help improve local water quality:

- Reduce impervious surfaces in your home landscape to reduce the volume of water leaving your home landscape.

- Install a rain garden to intercept stormwater or a rain barrel to retain runoff from impervious surfaces.

- Add vegetation to your yard.

- Manage your home lawn effectively.

- Plant a vegetated buffer along creeks and streams.

Reduce Impervious Surfaces

The most basic way to reduce runoff is to minimize the use of hard surfaces in your landscape that shed water (figure 3). Allowing more water to infiltrate back into the ground reduces the amount of stormwater leaving your yard, thus reducing the first flush of potential pollutants from entering local storm drains.

There are many permeable alternatives to pavement and asphalt when it comes to driveways, sidewalks, and patios. Permeable pavers can be both an aesthetic and water-conscious choice. Options include pervious concrete, pervious asphalt, interlocking pavers, brick grid/grass pavers, and gravel. These types of pavers allow water to infiltrate into the ground while still providing function in your landscape (figure 4).

Permeable pavers are composed of a layer of concrete or brick; the pavers are separated by joints filled with crushed aggregate that allow water to infiltrate between the pavers (figure 5). Porous pavers are generally a cellular grid system filled with dirt, sand, or gravel. Pervious pavers allow stormwater to percolate through the surface of the pavers rather than run off into surrounding areas (figure 6); they let the ground below the pavers “breathe.”

Pervious pavement does require maintenance, including visual inspection to remove sediment and debris to prevent clogging over time. In time, a deeper cleaning, such as vacuuming and/or pressure washing the surface could be necessary to maintain the permeability of the pavers.

The effectiveness of permeable pavers depends on the type of soil underneath. In clay soils, permeable paving water storage is reduced. You may need to seek professional consultation to determine if permeable pavers are appropriate for your site.

- Figure 2. Stormwater from your yard often runs off into storm drains where it is redirected to local water bodies.

- Figure 3. Example of a permeable pavement and vegetated yard.

- Figure 4. Example of how permeable pathways could be introduced in a landscape.

- Figure 5. Example of interlocking concrete permeable pavers.

- Figure 6. Example of pervious asphalt. The larger aggregate and lack of sand create voids that allow water to flow through the surface rather than run off.

Install a Rain Garden or Rain Barrel

Removing impervious surfaces is sometimes not an option. Instead, you can install a rain garden or a rain barrel to help capture runoff and hold it on-site longer. This allows water to seep back into the earth rather than run off into storm drains.

Rain gardens are shallow vegetated landscape depressions that slow water for a short time to provide water infiltration, pollutant filtration, native plant habitat, and effective stormwater treatment for small-scale residential or commercial drainage areas (figure 7). Rain gardens are part of stormwater management systems that can be both aesthetically appealing and functional. For an extensive list of rain garden plants and planting plans, see “How to Install a Rain Garden” (Extension publication ANR-2768) at www.aces.edu.

Rainwater harvesting is the collection and storage of rainwater in a container or in the landscape through a designed practice. Rainwater is usually collected from rooftops, greenhouses, sheds, and other relatively clean surfaces and stored in rain barrels or cisterns (figure 8).

This stored water can be slowly released back into the landscape through uses such as irrigation, car washing, plant watering, or toilet flushing. For an extensive guide on rainwater harvesting, see “A Homeowner’s Guide to Rainwater Harvesting in Alabama” (Extension publication ANR-2794) at www.aces.edu.

You can also use passive water harvesting, which is the process of slowing down water and encouraging it to soak into the ground. By altering the contours of the land, you can catch and direct stormwater runoff so that it is used effectively in your landscape (figure 9).

- Figure 7. Rain garden installed in front yard to capture stormwater runoff.(Photo credit: Mississippi Watershed Management Organization, CC BY-NC 2.0)

- Figure 8. Rain barrels can temporarily store water to be redistributed to a landscape.

- Figure 9. Rerouting stormwater through a designed riverbed or French drain can help reroute stormwater to vegetation.

Passive rainwater harvesting can be used along with a rainwater storage system (such as a rain barrel) or used alone. Examples of passive water harvesting include the use of berms and swales (infiltration basins) to help hold and retain water around plantings. Terraces can slow runoff from sloped areas and allow more infiltration at each level. French drains and dry streambeds also can be used to redirect water away from hardscapes and toward locations in your landscape that can absorb rainwater, reducing the need for irrigation. Dry swales (or arroyos) are shallow drainage areas that are dry most of the year but can accommodate some stormwater. To make dry swales an attractive landscape feature, consider using river stones, large rocks, and plantings to create an aesthetic feature.

The following native plants are well adapted for dry swales and shaded areas:

- Native trees: willow oak (Quercus phellos), sweet bay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana), ironwood (Carpinus caroliniana), wax myrtle (Myrica cerifera)

- Native shrubs: dwarf palmetto (Sabal minor), buttonbush (Cephalantus occidentalis), Virginia sweetspire (Itea virginica), coastal pepperbush (Clethra pepperbush)

- Native perennials: blue flag iris (Iris virginica), river oats (Chasmanthium latifolium), stokes aster (Stokesia laevis)

Minor changes to your home landscape do not require permits, but major work will require regulatory review. Contact a landscape architect or stormwater engineer if you need assistance. Contact the Alabama Department of Environmental Management before making structural changes to shorelines, streams, creeks, or waterfronts. Before digging, call Alabama 811 to locate any utility lines that may run across your property. Avoid planting rain gardens or gardens on top of septic systems.

Add Vegetation to Your Yard

Adding vegetation to your home landscape can help promote infiltration (figure 10). Soil health and plant root systems play a large part in rainwater infiltration. Soil is like a living, dynamic sponge that stores water, nutrients, and air. Soil gives beneficial organisms a habitat while filtering, trapping, and degrading contaminants in runoff.

Before selecting plants, it is important to understand the soil conditions and topography of your area. Soil conditions and sun exposure will determine your plant choices. Rain gardens and stream banks require plants that are well suited to medium-wet to wet conditions. Plants preferring uplands may do well along slopes or the tops of stream banks. For more information, go to www.aces.edu and search “landscaping.”

In selecting vegetation, consider the use of plants native to your area. Native plant species, in general, are less likely to require the use of pesticides, fungicides, and other chemicals to combat pest and disease issues. Species naturally found in your area also are likely to provide food and nectar for pollinators. The following perennials are a good place to start:

- Bee balm (Monarda)

- Blazing star (Liatris spicata)

- Spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

- Butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

- Oak leaf hydrangea (Hydrangea quercifolia)

- Coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata)

- Pink muhly grass (Muhlenbergia capillaris) (figure 11)

Avoid invasive plants, which are species that have the potential to spread and multiply rapidly while displacing native species. Examples include English ivy (Hedera helix), kudzu (Pueraria montana), sacred bamboo (Nandina domestica), and Chinese tallow tree (Triadica sebifera). Find a comprehensive list of invasive plants in Alabama on the Alabama Invasive Plant Council website.

- Figure 10. Adding vegetation to a home landscape can improve water retention.

- Figure 11. Native plant muhly grass.

Manage Lawn Areas and Soils Effectively

A rainscaped yard may transition away from a primarily turf landscape to make room for more vegetated beds. However, properly managing the sections of turf that do remain can provide many benefits. Areas with healthy turfgrass allow most of the rain to infiltrate and reduce soil erosion. The following practices can help you maintain a healthy lawn to maximize these benefits:

- Mow turf at higher heights (3 to 4 inches) to encourage deep root growth, which leads to a healthier lawn.

- Mow turf based on growth rate rather than on a schedule. This leads to a thicker lawn with fewer bare spots and provides greater water infiltration and better protection against soil erosion.

- Water less frequently to promote deeper roots; frequent watering can result in shallower root systems.

- Return clippings to the lawn to recycle nutrients, add organic matter to the soil, save time, decrease costs, and reduce the number of grass clippings transported off-site. Do not put clippings into nearby streams.

- Prevent overfertilization by reading and following instructions on the fertilizer label. Overfertilizing your lawn can lead to contaminated stormwater runoff. If any fertilizer lands on impervious surfaces, such as a sidewalk or driveway, be sure to sweep or blow it back into the lawn as you apply it to prevent movement with the next rain.

Plant Vegetated Buffers Along Creeks and Streams

Vegetated riparian buffers help filter pollutants from agricultural, urban, suburban, and other land cover through natural processes (figure 12). Restoring a stream’s riparian buffers (6 to 10 feet of vegetation on a stream bank) can play a large role in reducing stream bank erosion. The vegetation around stream banks provides important wildlife habitat and soil stabilization. Native grasses, trees, and shrubs have deep root systems that can provide both wildlife habitat and erosion reduction. Without plants and roots holding onto it, the soil is more likely to be washed away into waterways during heavy rain events (figure 13).

- Figure 12. A healthy vegetated riparian buffer provides stream bank protection.

- Figure 13. A heavily eroded stream bank without a riparian buffer.

If stream visibility is important to you, consider keeping a small pathway open to the stream’s entrance but vegetating the rest of the area. Surrounding a stream with turf grass or other short-rooted plants does not always provide the deep root system needed to keep soil from eroding. Never mow up to a stream’s edge as this removes the vegetation necessary for stream bank stabilization.along streams:

- Native trees: river birch (Betula nigra), sweetbay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana), silky dogwood (Swida amomum), native holly trees (Ilex cassine), black willow (Salix nigra), bald cypress (Taxodium distichum)

- Native grasses: switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), Indian grass (Sisyrinchium angustifolium), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), muhly grass (Muhlenbergia capillaris)

- Native shrubs: flowering dogwood (Benthamidia florida), elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), Virginia sweetspire (Itea virginica)

Place plants in their appropriate streamside planting zones. Some plants can tolerate waterlogged soils while others cannot. Research plants ahead of time to ensure you choose the right plant for the right place.

Homeowners can make a range of modifications to improve the water quality of their home landscape. Rainscaping your yard can provide a benefit to your community and to your downstream neighbors.

Additional Resources

Find more information on rainscaping and related topics on the Alabama Extension website, www.aces.edu.

- “Alabama Watershed Stewards Handbook”

- “How to Install a Rain Garden”

- “Guide to Harvesting and Planting Live Stakes for Stream Restoration”

- “Home Lawn Maintenance”

- “A Homeowner’s Guide to Rainwater Harvesting in Alabama”

- “Drought-Tolerant Landscapes for Alabama”

- “Protecting Pollinators in Urban Areas: Use of Flowering Plants”

Laura Bell, Administrator, Outreach Programs, Watershed Program Coordinator, Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences, Auburn University

Laura Bell, Administrator, Outreach Programs, Watershed Program Coordinator, Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences, Auburn University

New May 2022, Rainscaping Your Yard to Protect Water Quality, ANR-2892