Fish & Water

Turbid or muddy water in a recreational pond can be unsightly and is often caused by suspended clay particles in the water, known as clay turbidity.

Other sources of turbidity in ponds include algae, which typically gives the pond a green color, and heavier sediment, which tends to resolve itself much quicker than clay turbidity. However, a thorough discussion of those types of turbidity are outside of the scope of this document.

In clay turbidity, suspended clay particles reduce sunlight penetration into the water column, which lowers primary productivity (phytoplankton and zooplankton). This subsequently reduces fish and oxygen production because of decreased phytoplankton density and photosynthesis.

Clay turbidity in a pond can result from a number of different factors and can vary based on pond design, along with weather patterns and land use within the pond’s watershed. These variables might all influence runoff that may introduce clay particles into the pond. In addition, pond bottoms disturbed by cattle wading or fish feeding in the sediment can also experience clay turbidity.

Figure 1. Pond with heavy clay turbidity.

Turbidity caused by clay particles can be especially problematic compared to turbidity caused by other soil types. Clay particles are small and take much longer to settle out of the water; even if not managed, they can remain suspended. Negatively charged clay particles repel each other, much like two magnets, and can keep particles suspended in the water for extended periods. A water sample brought to an Alabama Cooperative Extension System office is shown in the following picture series (figures 2 through 8). This sample is in a closed bottle that was not moved for 200 days. Note that several weeks were required to observe significant signs of settling out of the water, indicating the presence of suspended clay particles. In a pond with continued disturbance, such as wind, rain, wave action, and cattle, the particles would continually stir and remain in the water column for much longer than in the controlled, undisturbed sample.

Once clay turbidity has been determined, there are two reliable treatment options to aid in settling clay particles in pond water. The first is to add organic matter, such as hay, manure, or cotton seed meal, to the pond. As these materials are decomposed by bacteria, carbon dioxide is created, acting as a weak acid in water and lowering the pH. This decrease in pH causes clay particles to floc or clump together, resulting in the precipitation or settling out of the clay particles. This technique has been effective with two or three applications of manure at a rate of 2,176.9 pounds per acre of water at 3-week intervals, applications of 75.8 pounds of cotton seed meal per acre of water, or 25 pounds of superphosphate per acre of water at 2-to-3-week intervals. In the long term, clay turbidity will be reduced, and the addition of nutrients can increase oxygen-producing phytoplankton. The biggest drawback with this approach is related to oxygen availability in the pond and the risk of fish kill soon after the initial application. With excessive clay turbidity phytoplankton (the primary source of oxygen for pond systems) density is often low, and oxygen production is already limited. The addition of organic matter will cause populations of bacteria to grow rapidly, consuming oxygen while breaking down organic matter, which can reduce oxygen concentration to lethal levels unable to support fish.

Clay Turbidity Persistence in Water Samples

Figures 2 through 8 show water samples containing clay-induced turbidity (right), with a spring water sample on the left for comparison. The samples are displayed at 0, 12, 25, 35, 42, 105, and 200 days after agitation. Note, even at 200 days postagitation, a significant amount of sediment has settled at the bottom of the bottle, yet the water above remains visibly stained, indicating persistent turbidity.

- Figure 2. Clay turbidity 0 days after agitation

- Figure 3. Clay turbidity 12 days after agitation

- Figure 4. Clay turbidity 25 days after agitation

- Figure 5. Clay turbidity 35 days after agitation

- Figure 6. Clay turbidity 42 days after agitation

- Figure 7. Clay turbidity 105 days after agitation

- Figure 8. Clay turbidity 200 days after agitation

The second method for decreasing clay turbidity in pond waters is the application of a chemical to drive a reaction. Products such as agricultural lime, gypsum, and alum can be used. However, large amounts of lime and gypsum are required to see a significant reduction in turbidity. While gypsum is safer for use and does have some residual effects on turbidity that alum does not, according to research done at Auburn University, an application rate of 250 to 500 mg/L of gypsum is required to have similar effects on turbidity as 15 to 25 mg/L, and alum is significantly less costly than gypsum.

Therefore, the most effective additive is alum (aluminum sulfate). Alum can sometimes be purchased through local farmers’ co-ops or chemical supply companies. It can also be purchased online and sometimes through landscape supply stores, as it has applications in landscaping. Alum is considered safe to fish unless applied at excessive rates. When added to water, alum produces a hydrogen ion that reacts with the alkalinity of the water, producing carbon dioxide. Through these reactions, the clay particles form groups and become heavy enough to settle out of the water. The results of alum treatments in ponds can be seen in a matter of hours. Alum should be mixed in a bucket of water and spread evenly over the pond’s surface. Slowly dumping the alum water slurry into the prop wash of a boat driven back and forth across the pond is an effective way to spread it.

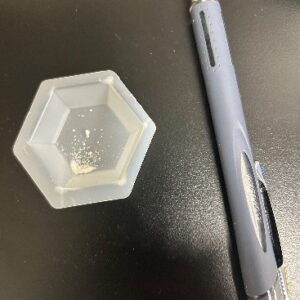

The application rate of alum will depend on the water chemistry of the pond and the turbidity level, but in experiments conducted at Auburn University’s fisheries research station, applying 54 pounds of alum per acrefoot of water was sufficient to improve clay turbidity. Though some recommendations are as low as half this amount and others are almost double. Given this range of recommendations. A simple way to test for the amount of alum necessary to clear turbidity in a particular pond is the “bucket test.” To conduct the bucket test, fill four separate 5-gallon buckets with exactly 5 gallons of turbid pond water each. Then, using a scale that can weigh to the 1/1000 of an ounce, weigh 0.007 ounces of alum for bucket 1, weigh 0.01 ounces for bucket 2, weigh 0.014 ounces for bucket 3, and weigh 0.018 ounces for bucket 4. Mix the alum in each bucket vigorously for 1 to 2 minutes, and then briefly every 5 minutes for the next 30 minutes. Then, a simple observation can be made of the lowest dose of alum that sufficiently clears the turbidity in the bucket:

- Bucket 1 represents approximately 30 pounds of alum per acre-foot of water.

- Bucket 2 represents approximately 45 pounds of alum per acre-foot of water.

- Bucket 3 represents approximately 60 pounds of alum per acre-foot of water.

- Bucket 4 represents approximately 75 pounds of alum per acre-foot of water.

In the absence of a scale appropriate for weighing such small quantities of alum, use a starting rate of 40 to 60 pounds per acre-foot with additional alum added if results are not noticeable within 30 minutes.

Example Calculation for Alum Application

Pond Size: A pond with a surface area of ½ acre and an average depth of 4 feet requiring a rate of 50 pounds per acre-foot

Calculation: 0.5 acres × 4 feet = 2 acre-feet 2 acre-fee × 50 pounds per acre-foot = 100 pounds of alum

Estimated Cost: 100 pounds × $0.80 per pound = $80

(Note: This rate is an example. The actual required amount may vary depending on conditions.)

- Figure 9. Only a small amount of alum at a rate equivalent to 50 pounds per acre-foot is needed to treat the sample used in the previous photo series.

- Figure 10. The same water sample as the photo series, re-agitated and treated with alum. This picture was taken zero minutes after treatment.

- Figure 11. The same water sample as above, re-agitated and treated with alum; picture taken 1 hour and 30 minutes after treatment.

- Figure 12. The same water sample as above, re-agitated and treated with alum; picture taken 3 hours after treatment.

Pond alkalinity should be above 20 parts per million (ppm) before beginning any alum application because of the drop in alkalinity expected from the chemical reactions explained above and the subsequent swings in pH. If pond alkalinity is below 20 ppm, ½ part hydrated lime can be applied for every part of alum in to maintain pH. An alternative and safer method is to raise the pond’s alkalinity using agricultural lime before applying the alum. If alkalinity is near 20 ppm, it should be monitored closely to ensure that it does not drop too low. A starting alkalinity of 50 ppm would be safer (see “Adding Agricultural Lime to Recreational Fish Ponds” on the Alabama Extension website at www.aces.edu). Though alum is not extremely expensive compared to many chemical pond treatments, the cost can become prohibitive, especially in larger ponds. For example, a 5-acre pond that averages 6 feet deep has 30 acrefeet of water. If 50 pounds per acre-foot were applied, a total of 1,500 pounds of alum would be necessary. Even at bulk prices, the cost would still exceed $1,000. Better management practices address the source of the turbidity rather than treat the symptoms of the problem, except in cases when immediate, though temporary, improvement is worth the expense.

Although there are effective methods for settling suspended clay particles from pond water, the source of the turbidity must be addressed or the problem will reoccur as there are no significant residual effects from alum treatments. Whatever caused the pond to become muddy in the first place will likely cause it to become muddy again after treatment if the underlying problem is not corrected.

If the source of the turbidity is eliminated and the cost of treatment deemed too high, the particles will eventually settle out; however, that is in a perfect world with no wind to stir or other factors that increase turbidity. Remember that the water sample pictures in this document were taken with the bottle completely undisturbed (no wind, no rain, no cattle, no boats, etc.) in a completely sealed bottle, and months later, the water was still stained from the presence of clay particles. In your pond, the time to settle clay turbidity will likely be much longer if you do not apply corrective treatments.

Works Cited

Boyd, C. 1990. Water Quality In Ponds For Aquaculture. Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station Auburn University.

Corey Courtwright, Extension Agent, Aquatic Resources, Auburn University

Corey Courtwright, Extension Agent, Aquatic Resources, Auburn University

New January 2026, Clay Turbidity in Recreational Ponds, ANR-3207