Crop Production

Water temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean affect weather patterns throughout the United States. Alabama is no exception—the reason why farmers, cattle producers, and others involved in agriculture not only should take note of this fact but also use it to guide their decision making.

What Is ENSO?

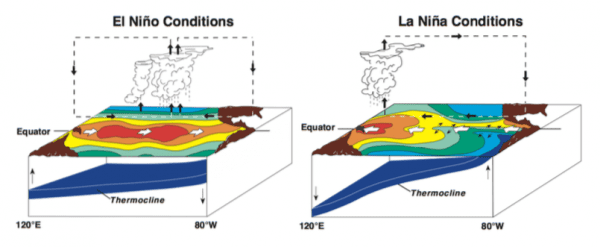

Abnormal warming or cooling around the equator during El Niño and La Niña events results in large- scale air-pressure fluctuations between the western and eastern halves of the Pacific Ocean. This, in turn, contributes to oceanic and atmospheric oscillation— a phenomenon known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). ENSO is expressed in three different phases—El Niño, La Niña, and Neutral—and greatly affects climate variability from year to year in different parts of the world, including the United States.

How Are El Niño and La Niña Detected and Predicted?

A number of entities comprising the Tropical Ocean Global Atmosphere Program work cooperatively to monitor the ENSO system. They use the data they collect to calculate indexes, such as the Southern Oscillation Index, the Nino 3.4 Index, and the Multi- variate ENSO Index. All of these indexes are mainly based on the variation in ocean/air temperature and pressure in the Pacific Ocean. The values of these indexes are used to predict ENSO phases. While El Niño and La Niña occur thousands of miles from Alabama, the ENSO Forecast better equips us to deal with their effects, whether these turn out to be hurricanes, tornadoes, untimely flooding, or severe droughts.

Figure 1. Situations in Pacific Ocean during El Niño and La Niña of ENSO (Photo Source: NOAA)

Important Characteristics of El Niño and La Niña Phases of ENSO

El Niño

- Steams from warm, humid air that forms clouds, resulting in tropical rainfall over the equatorial Pacific and that covers the entire eastern half of the Pacific Ocean.

- Occurs approximately once in every 4 years, lasting from 9 to 12 months.

- Is expressed as 4 degrees F to 6 degrees F above normal sea surface temperature between the date line and the west coast of South America.

- Is reflected in higher than normal air pressure near Indonesia and the western Pacific; lower than average air pressure in the eastern Pacific.

- Is expressed in increased winter precipitation in the southern United States.

- Is associated with fewer Atlantic hurricanes.

- Is linked with a greater likelihood of severe tornadoes in the southern United States.

La Niña

- Steams from warm, humid air that cools down with rainfall in the extreme western part of the Pacific Ocean.

- Is reflected as 2 degrees F to 6 degrees F below normal sea surface temperature between the date line and the west coast of South America.

- Is associated with below average air pressure in the western Pacific; higher than average air pressure in the eastern Pacific.

- Lasts as long as 1 to 3 years.

- Is expressed in decreased winter precipitation in the southeastern United States.

- Is linked with more Atlantic hurricanes and, consequently, greater risk for damaging storms in the southern United States and Caribbean Islands.

- Is reflected in a greater likelihood of severe tornadoes in the northern United States.

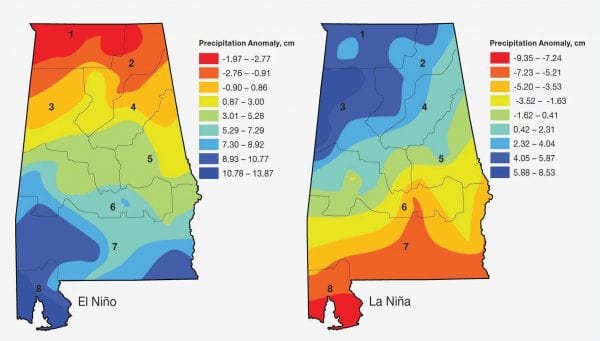

Figure 2. Precipitation anomaly in respect to historic averages during winter months (January through March) of El Niño and La Niña in Alabama. (Note: The numbers in the figures denote climate divisions of Alabama.)

Important Characteristics of El Niño and La Niña Phases of ENSO in Alabama

El Niño

- Is typically manifested by cold winters and lower temperatures than those associated with La Niña and Neutral winter phase.

- Is usually reflected in higher than average winter-spring precipitation in the southern part of the state, compared with lower averages in the northern region.

- During December through April, stream flow higher than La Niña in climate divisions 4 through 8 in Alabama.

La Niña

- Is associated with warmer winters compared to El Niño and Neutral winter ENSO phases.

- Is typically expressed by higher than average winter-spring precipitation in north Alabama than in south Alabama.

- Stream flow during December through April for climate divisions 1 through 3 in the northern part of the state higher in respect to El Niño.

Where to Look for Climate Information

- Historic climate data by state and county for each ENSO phase is available through the Climate Risk tool developed by the Southeast Climate Consortium (http://agroclimate.org/tools/).

- Information regarding weather and climate of Alabama; forecasts of near future; basic and advanced scientific facts; news and climate-related risks on agriculture and natural resources are available at www.aces.edu/climate.

ENSO Impacts on Southeastern Agriculture

During El Niño Years

- Corn yields are usually lower than historic averages.

- Harvest of summer crops, such as corn, peanuts, and cotton, may be delayed because of more rains.

- Frequent rains at the end of August and early September might increase the risk of buildup of Hessian fly populations on winter wheat.

- Susceptible and moderate peanut cultivars have higher intensity of tomato spotted wilt virus.

- Yields of winter vegetables, such as tomatoes, bell peppers, sweet corn, green peppers, and snap beans, are lower.

- Fungal and bacterial diseases, especially bacterial spot of tomato and bell peppers, present higher risks.

- Winter pasture crops may benefit from wetter weather, but planting and harvesting operations may be affected by heavy rainfall.

- Growers may have to reduce the dormancy-compensating sprays to temperate fruits, such as peach, nectarine, blueberry, and strawberry, due to increases in chill accumulation days.

- Strawberry growth is slower than normal. Risks of fungal diseases, such as anthracnose, botrytis fruit rot, and angular leaf spot, is higher.

During La Niña Years

- Corn yields are generally higher if irrigated. Reduction in yield (up to 12 percent) might be expected in the years following La Niña.

- Planting of nonirrigated corn should be delayed until May to match summer rainfall with pollination and silking stages.

- High wheat yield in north Alabama contrasting with El Niño phase that tends to favor wheat yield in the southern areas of the state.

- Warm winter and spring weather might result in faster development of Hessian fly populations.

- La Niña weather increases the risk of barley yellow dwarf (BYD) viral disease in small grains.

- Intensity of tomato spotted wilt virus is lower.

- Winter tomato and green pepper yields are expected to increase.

- Less fungal and bacterial diseases to winter vegetables might be expected; however, virus spread by thrips, such as tomato spotted wilt, and white fly, such as tomato yellow leaf curl, can be a major problem.

- Pasture crops exhibit lower yields. Example: reduction in yields of ryegrass up to 40 percent might be expected.

- Growers may need to increase the number of dormancy-compensating sprays to temperate fruits due to decreased chill accumulation. The population of annual broadleaf weeds, which are the host for sucking bugs of peaches, might increase.

- Reduction or elimination of flowering of subtropical fruits, such as mango, lychee, and longan, but production of tropical fruits, such as banana, guava, and papaya, increases. Disease problem is lower, but insect pressure may increase.

Download a PDF of The ABCs of Climate Variability, ANR-1437.