Bees & Pollinators

When you think of bees, the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) probably comes to mind right away. Most people are familiar with its bustling hive of worker bees, drones, and a single queen, all working together in a highly organized colony. However, Alabama is home to approximately 500 other bee species that lead a wide variety of lifestyles along a spectrum of social complexity.

Solitary Bees

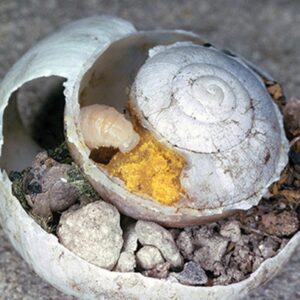

Figure 1. Nests within hollow stems and underground. (Image courtesy of Abigayle Crochet, Auburn University Native Bee Lab)

About 90 percent of bee species in the United States are solitary. In this lifestyle, each mature female builds her own nest and forages for pollen and nectar to feed her offspring. Ground-nesters make up the bulk of the solitary bees, with about 70 percent of the species digging underground tunnels to rear their young (figure 1). Ground nests are easiest to spot during the spring when the males of many solitary bee species swarm the nest entrances in hope of mating with a female.

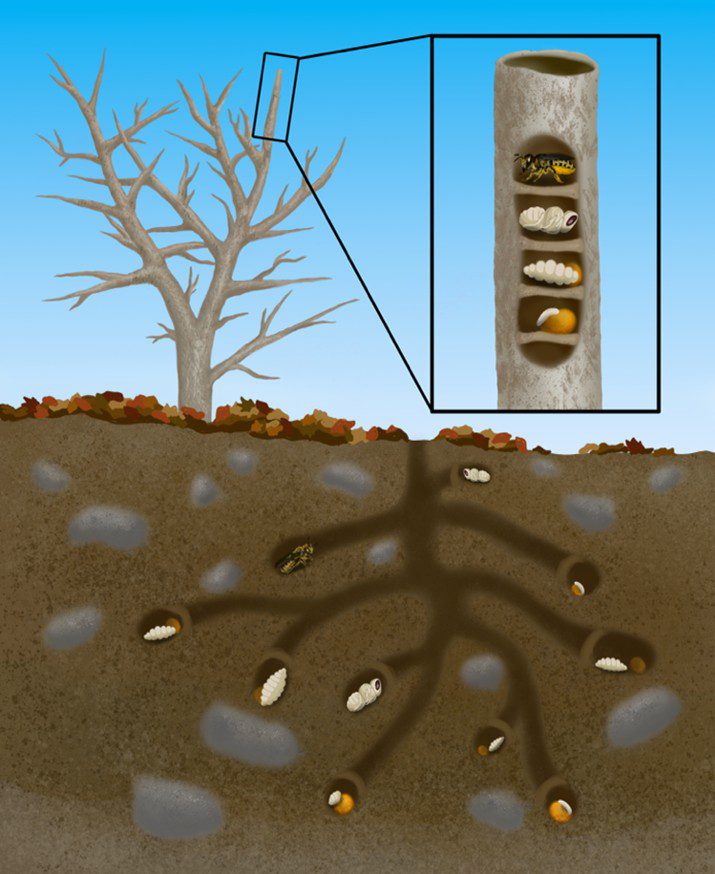

The remaining 30 percent of solitary bees are cavity nesters, creating their nests in a variety of tunnels and crevices. While some simply chew out the soft central pith of stems and twigs, others are more creative, constructing their nests within snail shells (figure 2), beetle burrows, abandoned wasp nests, or between rocks.

Eusocial Bees

On the opposite end of the social spectrum are bees that exhibit true sociality, also known as “eusociality.” Alabama native E. O. Wilson helped define insect eusociality in his 1971 book The Insect Societies. According to Wilson, a species is considered eusocial if it meets all three of the following criteria:

- Cooperative brood care: Females within the colony care for offspring that are not their own.

- Reproduction division of labor: Females are separated into reproductive individuals (queens) and nonreproductive workers.

- Overlapping generations: Multiple generations live together, with each generation contributing to colony tasks.

Within the United States, only two groups of bees meet these requirements and can be considered truly eusocial: bumblebees (Bombus spp.; figure 3) and the introduced European honey bee (Apis mellifera; figure 4). Eusociality makes these bee groups vital for crop pollination in the United States. Because their colonies can support large numbers of worker bees and are easily transported, bumble and honey bees are used in the production of almonds, apples, tomatoes, and other crops in the United States.

- Figure 2. Nest of a mason bee (genus Osmia) within a snail shell. (Photo credit: A. Krebs; from Müller et al. 2018, CC BY 4.0)

- Figure 3. A bumble bee hive with worker bees and wax cells containing nectar or developing larvae. (Photo credit: Christa R./Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0, photo cropped)

- Figure 4. The intricate hive structure created by European honey bee worker bees (Apis mellifera). (Photo courtesy of Peter R. Marting, Smith Bee Lab, Auburn University)

Parasocial Bees

And then, there are the odd ones out; bees that exhibit some, but not all, of the three eusocial traits. They are referred to as “parasocial.” Parasocial species can be divided into three categories based on their social organization:

- Semisocial bees: These species meet nearly all of the eusociality criteria, but there are no overlapping generations within the nest. Because all individuals belong to the same generation and have synchronized development, they can easily coordinate to complete tasks within the nest (e.g., Augochloropsis metallica; figure 5).

- Quasisocial bees: Several females share a single nest and cooperate in building and provisioning it, but all females lay eggs. By sharing chores like nest guarding and collecting food, each bee has less work, more offspring survive, and the group can gather nectar and pollen faster than a lone female could (e.g., Euglossa dilemma; figure 6).

- Communal bees: Multiple females share the same nest entrance but do not cooperate, with each female provisioning for her own offspring independently. However, unlike the other two types of parasocial bees that continually bring food to their offspring as they grow, communal bee mothers take a more hands-off approach, instead opting to provide them with a single ball of pollen before they hatch. Living communally reduces risks from predators and parasites, improves nest defense, and creates a more stable microclimate (temperature and humidity) for developing offspring(e.g., Agapostemon virescens; figure 7).

- Figure 5. The metallic epauletted sweat bee (Augochloropsis metallica), one of Alabama’s primarily semisocial native bee species. (Photo credit: USGS Bee Lab/Flickr)

- Figure 6. The dilemma orchid bee (Euglossa dilemma) is an example of a quasisocial bee species. This species is established in Florida but is not known to occur in Alabama. (Photo credit: USGS Bee Lab/Flickr, CC0)

- Figure 7. The bicolored striped sweat bee (Agapostemon virescens) is one of Alabama’s primarily communal native bee species. (Photo credit: Daniel Mullen/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND)

Social Plasticity

Figure 8. One of Alabama’s native socially plastic bee species, the orange-legged furrow bee (Halictus rubicundus). (Photo credit: Leon van der Noll/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

The final (and, arguably, most fascinating) bee lifestyle is social plasticity. Several native bee species (primarily within the sweat bee family, Halictidae) can change their social structure in response to a changing environment and resource availability. For example, the orange-legged furrow bee (Halictus rubicundus; figure 8), a ground-nesting native species, forms social colonies in warmer climates but tends to live solitarily in colder regions. There are physical differences between members of this species depending on their degree of sociality: orange-legged furrow bees that live in social nests tend to have more sensory structures on their antennae, which are used to recognize nest mates and enhance cooperation in the colony. Remarkably, these bees quickly adjust their lifestyle when moved to a new environment; in one experiment, the offspring of populations transplanted from a cold to a warm climate immediately adopted social nesting.

Conclusion

From solitary to eusocial, Alabama’s bees exhibit a broad range of lifestyles. These diverse strategies have been shaped over time by climate, resource availability, and ecological pressures. Supporting bees across a variety of lifestyles and habitats will help ensure a future rich with pollinators.

References

- Boulton, R. A. & Field, J. (2022). Sensory plasticity in a socially plastic bee. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 35(9), 1218–1228.

- Cane, J. H., Griswold, T. & Parker, F. D. (2007). Substrates and materials used for nesting by North American Osmia bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes: Megachilidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 100(3), 350–358.

- da Silva, J. (2021). Life History and the Transitions to Eusociality in the Hymenoptera. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 727124.

- Kline, O. & Joshi, N. K. (2020). Mitigating the effects of habitat loss on solitary bees in agricultural ecosystems. Agriculture, 10(4), 115.

- Lee-Mäder, E., Spivak, M., Evans, E. (2010). Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists. United States: Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education.

- Müller, A. D., Praz, C. & Dorchin, A. (2018). Biology of Palaearctic Wainia bees of the subgenus Caposmia including a short review on snail shell nesting in osmiine bees (Hymenoptera, Megachilidae). Journal of Hymenoptera Research, 65, 61–89.

- Wild Bee Conservation (n.d.). Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

Sara Kirby, Graduate Research Assistant; Anthony Abbate, Assistant Research Professor; and Selina Bruckner, Assistant Extension Professor, all in Entomology and Plant Pathology, Auburn University.

Sara Kirby, Graduate Research Assistant; Anthony Abbate, Assistant Research Professor; and Selina Bruckner, Assistant Extension Professor, all in Entomology and Plant Pathology, Auburn University.

New December 2025, Lifestyles of Alabama’s Bees: Solitary, Social & Somewhere In Between, ANR-3211