Beef

In most cattle operations, the greatest expense is attributed to feeding costs. Several alternative feedstuffs can reduce overall feed costs for beef cattle. Learn the factors to consider when choosing feed and the advantages and limitations of cotton, peanuts, soybeans, corn, and brewer’s grains as alternative supplements to regular feed options.

Feed costs represent the largest single cost item in most beef operations. In many economic analyses, feed costs represent around 60 to 70 percent of the variation in profit or loss differences among herds.

Many beef producers routinely use byproduct feeds, while numerous others use them only sporadically, such as during drought conditions when available forage is limited. This publication discusses common byproducts used in Alabama and across the Southeast and how to maximize their use on-farm.

When selecting a feed supplement, it is important to evaluate what your herd may lack in their diet. When providing additional support to the cow-calf herd, there’s a higher chance of encountering energy limitations, while for growing and replacement animals, protein might become a restricting factor. All feeds and feedstuffs are evaluated for energy and protein using total digestible nutrients (TDN) and crude protein (CP) values, respectively.

Forage testing is highly recommended for pasture, hay, or baleage/haylage products you plan to feed your herd. This testing will help you identify what needs to be supplemented and when. For example, a fall-calving herd may need greater energy supplementation in September and October when warm-season pasture becomes limiting and cows are in peak lactation.

When searching for a supplemental byproduct for your cattle, consider the following:

- Moisture content

- Nutritional profile

- Contaminants

- Availability and seasonality

- Storage and handling requirements

Moisture content. Many byproducts contain excessive amounts of moisture that can create several problems. A typical high-moisture byproduct is wet brewer’s grain that normally contains 70 to 80 percent moisture. This means that you are paying for a product that is mostly water. For instance, for every 24-ton truckload of wet brewers’ grains purchased, 18 tons of water are delivered but only 6 tons of dry feed are available.

When comparing feeds with different moisture contents, the overall price per pound of nutrients also changes. This means that a high-moisture byproduct may cost you more pound-for-pound when compared to a low-moisture supplement. When making a supplement selection, it is critical to compare dry matter (DM) to help reduce any variability caused by moisture content.

Nutrient profile. Most byproducts are classified as an energy, protein, or roughage source. Feeds with high TDN values (greater than 70 percent) generally fall into the energy category. These byproducts are usually sourced from cereal grain and corn processing and milling. Protein supplements (greater than 20 percent CP) are often sourced from oilseeds and cotton production. Byproducts like whole cottonseed, dried distillers’ grains (DDGS), and brewers grains can be classified as an energy and protein supplement due to their high nutritional quality. This is why it is important to identify first what your herd needs. Roughage sources are often the fibrous component, such as hulls, shells, and straw, removed from grains. These products are often fed as forage extenders or hay replacements.

Contaminants. An unlimited potential for including numerous contaminants exists when feeding byproducts. For example, cotton gin byproducts may consist of something as simple as unwanted weed seeds or as complex as pesticide residues. Some byproducts may have concentrated amounts of mycotoxins, or fungi, as a result of screening or sorting procedures.

Cereal grains and corn byproducts are particularly susceptible to fungal contamination. Cattle that consume large amounts of mycotoxins can become severely ill and die if not caught early. Sending a sample for feed analysis is a quick way to detect possible contaminants in your byproducts.

Transportation and storage. Most of the cost associated with using byproducts for cattle feed comes from moving them from the point of origin to the feeding location. Many byproducts are transported as 24-ton loads by tractor-trailers and require adequate facilities to handle the deliveries.

First, the farm must have adequate space for these large trailer’s entry, turnaround, and exit. If the byproducts are to be unloaded into storage bays, absolute minimum width is 14 feet. Eave height will always be a problem if dump trailers are used; however, trailers with live bottoms or a walking floor can unload easily into a bay or shed with an eave height of 16 feet. When planning such a facility, it is always better for it to be too large rather than too small. Also, plan to have the bay accessible from both sides. When a new load of feed is added, you can begin accessing from the opposite side. This way, the older feed is used first.

Regulations. Any potential regulations concerning a byproduct feed should always be considered. Accepted byproducts have been defined by the American Association of Feed Control Officials and must be sold with a guaranteed analysis.

Availability. Consider seasonal availability. Many byproducts are produced all year, while supplemental feeds for cattle may only be needed when forage is unavailable. Thus, storage facilities are needed so the byproduct can be bought at the lowest price. It can then be fed at a later date when needed. If you wait until the feed is needed, you are at the mercy of the markets, and the byproduct may no longer be economical.

Byproducts in Grazing Systems

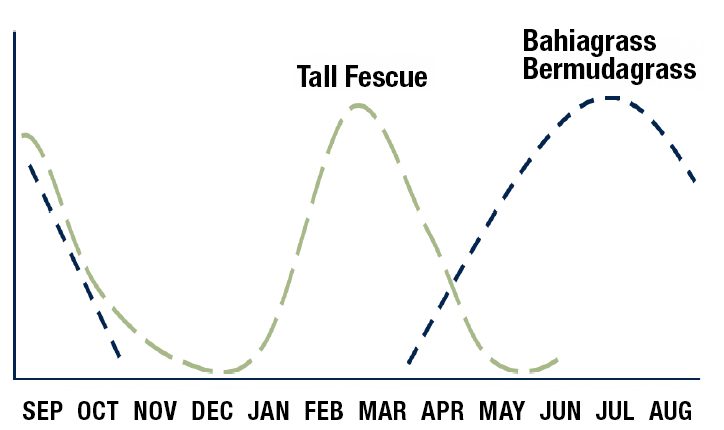

Figure 1. Growth curves of common perennial grass species in Alabama.

The use of byproducts as nutrient sources for beef cattle will continue to be driven by economics. Consider what you are getting in return when deciding to supplement your herd. Providing supplements to herds can improve performance and efficiency in meeting operation-specific goals, such as reproductive and marketing goals. Byproducts can also help extend pasture availability and provide additional grazing days on established southeastern pastures. The southeast depends on perennial forages. When using these species, there are key times of the year when available dry matter becomes limiting. Figure 1 shows production curves for primary perennial species in Alabama.

Supplementation with byproduct feeds can have benefits for pasture-based systems. Cattle consuming supplemental feeds have the potential to cycle between 70 to 80 percent of consumed nutrients back to the pasture. This provides a feedback opportunity to supplement pastures as well as grazing herds.

Cotton

The cotton industry, quite prevalent in Alabama, generates several byproducts used as beef cattle feeds. These are whole cottonseed, cottonseed hulls, cottonseed meal, gin trash, and cotton mote. As cotton is ginned, the gin trash is sent outside the gin and stacked in large piles; the seed is extracted from the boll. Ginned cotton is used in textile mills for manufacturing various cotton products. The cotton is further refined at the textile mill where yarn is produced. The byproduct

of this procedure has been called cotton mote by many producers. It should be referred to as textile mill waste because some gins also produce what is referred to as cotton mote. The seed can also be further processed for extracting oil. The two remaining products are cottonseed hulls and cottonseed meal.

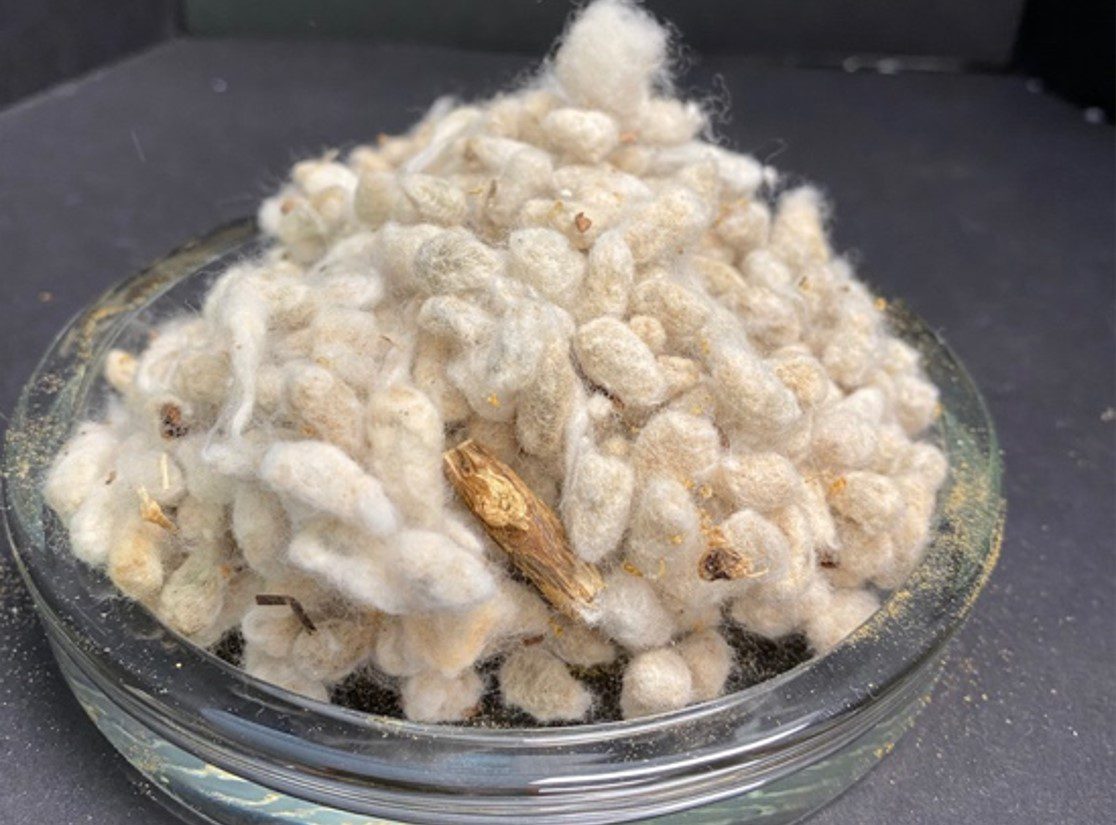

Figure 2. Whole cottonseed. (Photo credit: Brandon Smith, Department of Animal Sciences, Auburn University)

Whole cottonseed. Cottonseed can produce abundant amounts of energy. A good source of protein, cottonseed will typically contain 80 percent TDN and 24 percent crude protein. The limiting factor for its use in beef cattle diets is the fat content, which is approximately 20 percent. Because high-fat diets can affect the digestive health of cattle, an adaption period may also be needed to transition animals to whole cottonseed. Once cattle are adapted to whole cottonseed, the fat content becomes an intake limiter.

Feeding whole cottonseed in large quantities can also affect the fertility of beef cattle due to the presence of gossypol, a secondary compound produced throughout the plant. Avoid feeding whole cottonseed to bulls before the breeding season.

Whole cottonseed should not be fed in V-shaped self- feeders because the fuzzy seed will bridge, and cattle will not have continual access to the feed. For this reason, cottonseed should be stored in a covered shed or feed bay, not in feed bins. Fuzzy seed will not auger or gravity- flow very well. Seed is generally handled with front-end loaders or by hand.

Cottonseed meal. Cottonseed meal is an excellent source of natural protein for beef cattle. As a supplement to forage, it works quite well when limited fed to about 2 to 4 pounds per day. It also works well when fed as a hot mix (mixed with salt so it can be offered free-choice in self-feeders). Cottonseed meal contains 44 to 45 percent crude protein (dry matter basis), 75 percent TDN, and, like whole cottonseed, can contain gossypol.

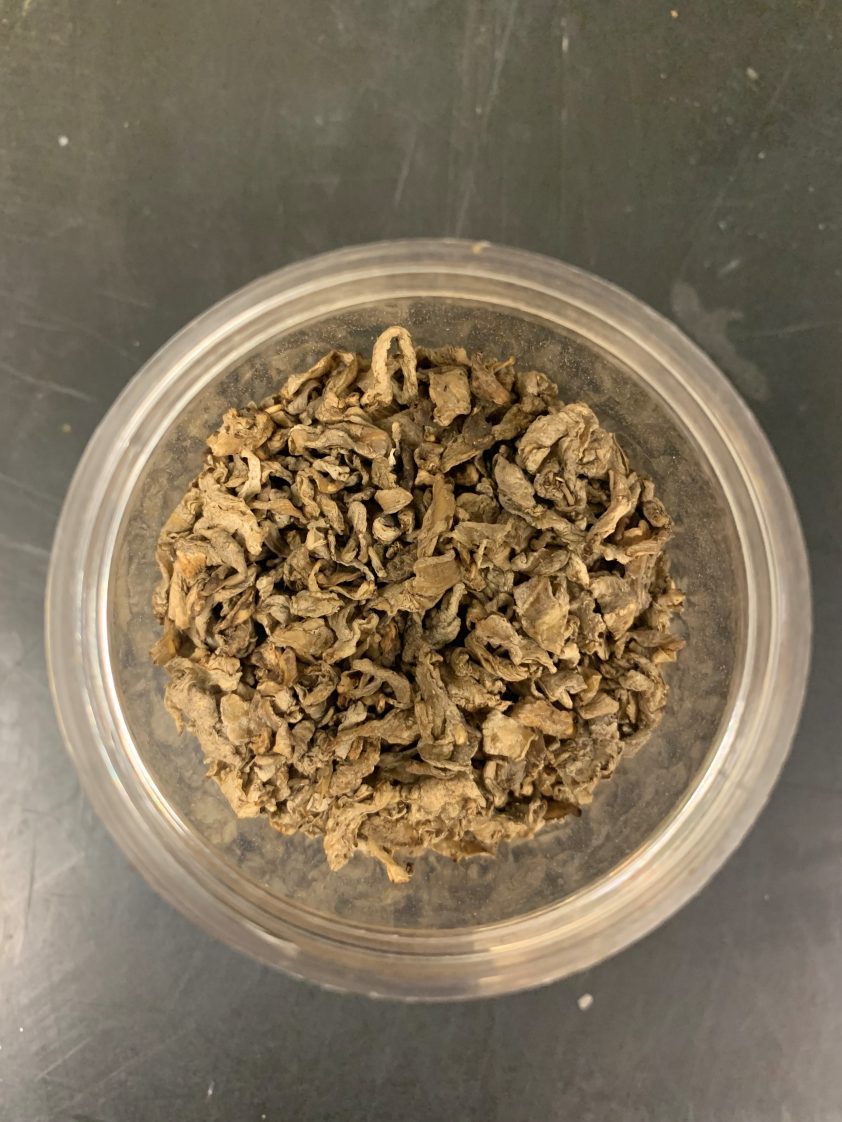

Figure 3. Cottonseed hulls. (Photo credit: Brandon Smith, Department of Animal Sciences, Auburn University)

Cottonseed hulls. Cottonseed hulls are a very palatable roughage source. They are extremely low in nutritive value (42 percent TDN and 4 to 5 percent CP) and should only be used as a source of roughage. They are a popular roughage source for high-grain diets because of their ease of handling compared to grinding hay. It is important to mix a roughage source into a complete diet to support healthy rumen function. If grinding hay is not an option, cottonseed hulls may be useful.

Gin byproduct (gin trash or cotton burs). Gin byproduct consists of everything in raw cotton except the cotton fiber and the seed. Many Alabama gins produce byproduct that contains approximately 40 to 48 percent TDN and 10 to 13 percent CP. In various research trials across the state, palatability has been good in brood cows and stocker cattle.

The biggest deterrents to its use as a roughage source are those associated with logistics. It is dusty when handled and is quite bulky to transport. Baled gin byproduct can limit dust and transportation issues, but another factor to consider is that many gins will add water as the material is expelled from the gin to decrease potential dust problems. Therefore, baled gin byproduct may undergo a heating period similar to high- moisture hay. Store baled gin trash in a well-ventilated barn to avoid overheating and fire hazards.

Peanuts

Figure 4. Gin byproduct (baled versus loose).

Peanut production is prevalent in the southern half of Alabama. Peanuts create several byproduct feeds, including broken and cull nuts, skins, hulls, and vines that can be used as roughage.

Raw peanuts. Because of their high monetary value, very few whole peanuts are used as cattle feed, although they can be used when available. The nutritional analysis is as follows: 38 percent fat, 24 percent protein, and 95 percent TDN. Similar to whole cottonseed, the limiting factor is the fat content. A maximum of about 4 pounds per head per day for mature cows should be fed. As with any high-fat content feed, introduce it to cattle gradually.

Occasionally, raw peanuts are available as a result of aflatoxin contamination. In this case, an accurate measurement of the aflatoxin concentration should be determined and the feed used accordingly. Generally, beef cattle can tolerate up to 200 to 400 parts per billion (ppb) in their diet, depending on the size and age of the animals.

Peanut skins. Peanut skins have a low bulk density and, therefore, create some logistical handling problems. The average chemical composition is 25 percent fat, 17 percent protein, and 65 percent TDN. A substantial amount of tannins are also found in peanut skins (approximately 20 percent). Tannins are unpalatable and bind protein in the diet, making it less digestible. Research conducted to evaluate the use of peanut skins in cattle diets indicates they should not exceed

15 percent of the total diet.

Peanut hulls. Peanut hulls are a roughage source, containing 8 to 10 percent protein and 43 to 45 percent TDN. Peanut hulls are most often found in the whole or pelleted form. When other roughage sources become limited, such as during a drought, many producers consider using peanut hulls. Pelleted peanut hulls should be included at most 20 percent of the diet. The more processed peanut hulls are, the less effective fiber value they provide.

Peanut hay. Peanut hay can have moderate feed value when properly cured and baled. Most peanut hay contains 13 to 17 percent protein and 55 percent TDN. Peanut hay is palatable to beef cattle. If excessive rain falls on the vines while curing, mold as well as elevated ash content as a result of the inverting process that places soil on the vines can be a problem. Peanut hay should be wrapped or stored inside because excessive dry matter and nutrient loss will occur with unprotected bales. Producers should note that many chemicals used in peanut production are not labeled for use in livestock production.

Soybeans

Whole soybeans. Soybeans are primarily processed for their oil, which leads to the generation of two primary byproducts—soybean meal and soybean hulls. The nutritional analysis of soybeans indicates that they contain approximately 20 percent fat, 40 percent protein, and 92 percent TDN. Raw soybeans contain urease and should not be used with feeds that contain urea or nonprotein nitrogen.

Figure 5. Soybean hulls.

Based on their fat content, cattle should be eased on to whole soybeans to prevent rapid diarrhea. Increase up to about 5 pounds per head per day. Once adapted, cattle may consume as much as 6 or 7 pounds per day. The whole soybeans should be coarsely ground for optimum utilization. When soybeans are ground through a hammermill, they can become gummy. To help reduce this problem, mix the soybeans with corn or other feedstuff before grinding. Palatability is generally not a problem.

Soybean hulls. Soybean hulls (soyhulls) are the skins of the soybean, which come off during processing. These soyhulls are quite small and not very dense. Therefore, many soyhulls are pelleted to increase ease of handling and bulk density. The loose and pelleted hulls are equal in nutritional value.

Despite the positive attributes of feeding soyhulls, some negatives do exist. At high intake levels (greater than 7 pounds per day), soyhulls are conducive to bloat, and a bloat preventative should be used. A satisfactory method would be to feed a mineral supplement containing an ionophore, such as Rumensin or Bovatec, or to provide a bloat preventative, such as a surfactant. Always provide some access to long-stem roughage, whether it be hay or grazing. Quality of the roughage is not as important as particle size. Bloating has only been a problem in growing calves; brood cows are not prone to bloat as a result of consuming soyhulls.

Wheat

During the wheat milling, about 75 percent of the grain becomes flour, and the remaining 25 percent is used as livestock feed. The resulting byproducts are referred to as millfeed, wheat mill run, or wheat middlings (midds). There is little consistency in terminology when talking about these products, and, in general, they are brokered in various combinations and marketed generically as wheat midds. Wheat byproducts are highly palatable to cattle, so pair these byproducts with a roughage source to prevent excessive diarrhea.

Wheat bran. Wheat bran consists of the outer coating of the wheat kernel that is removed during the milling process. Bran contains large portions of digestible fiber that cattle can utilize. Estimates of the nutritional quality of wheat bran are 70 percent TDN and 17 percent CP.

Figure 6. Pelleted wheat midds.. (Photo credit: Brandon Smith, Department of Animal Sciences, Auburn University)

Wheat midds. Wheat midds contain 17 to 18 percent protein and 73 to 80 percent TDN. Depending on the source, they are available as loose meal or as pellets. The meal is fine and not very dense. Pelleted wheat midds cannot be stored for any length of time during hot, humid weather. The pellets readily absorb moisture, swell, soften, and fall apart. Pelleted wheat midds do not react like other stored grain and will deteriorate rapidly. In the Alabama humidity, it is best to get only

a winter’s supply instead of trying to store the pelleted wheat midds over the summer.

Research in Kansas and Oklahoma has shown wheat midds equal to corn and soybean meal as a winter supplement for brood cows consuming low- to-medium- quality forage. Results from South Dakota and North Carolina have shown that calves can be backgrounded on free-choice hay and free-choice wheat midds with gains of 1.7 to 2.0 pounds per day. In these trials, the researchers reported no problems with bloat or acidosis. Remember that some danger always exists when feeding concentrates free choice.

Oats

Like wheat, oats undergo milling that yields byproducts suitable for cattle consumption. Oat groats, the dehulled oat kernels, are obtained by removing the outer hull of the oat kernel, resulting in oat hulls. Because of the high demand for oats in human and horse diets, whole oats are often not economically viable for feeding cattle. However, in some cases, other oat byproducts may become available at a competitive price.

Oat hulls. The nutritional value of oat hulls is around 56 percent TDN and 6 percent CP. Crude fiber (CF) of oat hulls is about 35 percent. The relatively high CF and low CP values make oat hulls a decent byproduct when a roughage source is needed. However, because of the low bulk density, shipping and transportation obstacles may prohibit their efficient use.

Rice

Most rice in the United States is milled in Arkansas; however, the byproducts can be shipped to Alabama at competitive prices. Paddy rice is harvested from the field. After drying, the first milling step is to remove the hull, yielding brown rice and rice hulls. Then the outer layer is removed from the brown rice to yield white rice and rice bran. The byproducts available for cattle feed are rice hulls, rice bran, and a combination of the two, which is referred to as rice mill feed.

Rice hulls. Rice hulls do not burn easily, do not absorb water readily, and deteriorate slowly. Their overall nutritional value is low and a poor source of energy and protein; however, rice hulls may be used as roughage in limited quantities. Most rice hulls are blended with rice bran so they can be fed in the form of rice mill feed.

Rice bran. Rice bran is a finely ground material generally containing 15 percent crude protein, 13 to 20 percent fat, and 83 percent total digestible nutrients. However, rice bran’s extremely variable ash content may negatively impact overall nutrition quality. Test each batch of rice bran to evaluate ash content before feeding. In an Auburn University study involving 88 weaned calves, half were offered free-choice hay and free-choice rice bran, while the other half were offered free-choice hay and soyhulls equal to the level of rice bran consumption. During a 42-day backgrounding period, the calves offered rice bran consumed 6.5 pounds of hay per day and 8.25 pounds of rice bran per day with gains of .58 pounds per day.

Corn

Corn grain is an extremely high-energy feed that is quite palatable to cattle. Several byproducts from corn can also be used as feed for beef cattle. Some common corn byproducts used in Alabama are hominy feed, corn gluten feed, and corn screenings.

Hominy feed. The dry milling process transforms corn into corn meal, hominy, and grits for human consumption. One of the resulting byproducts from this process is hominy feed, a mixture of corn bran, corn germ, and a portion of the starch. It contains greater than 4 percent fat and 10 to 12 percent protein. Its feeding value is considered to be equal to that of corn. Hominy feed is a finely ground product that works well for mixing with other ingredients. Feed it in much the same way you would feed corn grain.

Figure 7. Corn gluten feed. (Photo credit: Brandon Smith, Department of Animal Sciences, Auburn University).

Corn gluten feed. This product results from the wet milling of corn to produce starch, oil, and syrup. Corn gluten feed contains the bran and the steep liquor and may be marketed as either a wet or dry product.

Processors differ in product handling, resulting in variations among corn gluten feed types. Excessive heating during processing can alter corn gluten feed’s smell, color, nutritional value, and palatability. Excessive heating often binds available protein into an unavailable form, reducing overall feed value. Generally, the bran portion is partially dried by pressing, and then the steep liquor is added to produce wet corn gluten feed (40 to 65 percent moisture content), or additional steep liquor is added, followed by drying. Some processors may also add corn screenings to the final mix.

In some cases, the dried product will be pelleted. The product is fairly consistent from a particular processing plant but may vary more than 18 percent and may be as high as 23 to 24 percent. The TDN content ranges from 80 to 87 percent, and the variation primarily results from drying. In a Kentucky study, heifers grazing stockpiled fescue were supplemented with 9 pounds of corn, soyhulls, or corn gluten feed, and daily gains were 1.45, 1.58, and 1.83 pounds per day for the three supplements, respectively.

In research conducted in North Carolina, steers were supplemented with 6 pounds of a corn/soybean meal mix, corn gluten feed, or a 50:50 mix of the two. Daily gains were 2.76 for the corn/soy, 2.62 for the 50:50 mix, and 2.40 for the corn gluten feed. Soyhulls, corn gluten feed, or wheat midds were fed free-choice to calves consuming fescue hay. Those offered soyhulls consumed 19 pounds of soyhulls per day and gained 3.31 pounds per day; calves offered corn gluten feed consumed 13 pounds of supplement and gained 2.93 pounds per day, and those offered wheat midds consumed 12 pounds and gained 2.23 pounds per day.

Dried Distillers’ Grains

Figure 8. Dried distillers’ grains. (Photo credit: Brandon Smith, Department of Animal Sciences, Auburn University).

Distillers’ grains are a byproduct of grain fermentation to produce alcohol. In recent years, the ethanol industry’s growth in the United States has led to an increased supply of dried distillers’ grains in the market. Ethanol is primarily produced from corn but can also be made from other grains. Availability is usually concentrated in areas near distilleries and ethanol facilities. On average, dried distillers’ grains are an excellent energy and protein source, containing 90 to 95 percent TDN, 28 to 30 percent CP, and 10 percent fat. Similar animal performance levels have been reported when diets with up to 20 percent of their DM from distillers’ grains are compared with a control diet of corn and soybean meal for brood cows.

Additional research studies have shown that distillers’ grains can be included at up to 40 percent of the diet on a dry-matter basis without negatively affecting performance. The nutritional value of 3 pounds of dried distillers’ grains is roughly equivalent to feeding 2 pounds of corn plus 1 pound of soybean meal. However, the nutritional composition of distillers’ grains can be quite variable. Conducting a feed analysis before feeding is strongly recommended to determine if high levels of minerals are present. Distillers’ grains are high in phosphorous and can lead to Ca:P imbalances (or a Ca:P ratio of greater than 1:4). Feeding a mineral containing Ca that is low in or free of P can adjust the Ca:P ratio to the acceptable level of 1:4. Additionally, the sulfur content of distillers’ grains can be highly variable. Keep this in my mind when formulating a complete ration with DDGS.

Citrus and Beet Pulp

Citrus pulp. Most of the citrus pulp produced in the United States is in Florida. Citrus pulp contains approximately 70 percent TDN and 6 to 9 percent protein. Loose citrus pulp has a low bulk density, so much of it will be pelleted to facilitate transportation. Common terminology will refer to the pulp as 80:20 or 60:40. These ratios indicate what percent of that load will be pelleted and loose. The pelleted pulp can be heat damaged during the pelleting process, so it is essential to note the color of the pellets. Yellowish orange is the original color, with darkening toward a black color indicative of overheating.

Figure 9. Beet pulp.

For brood cows needing 3 to 7 pounds of an energy supplement per day, citrus pulp is an excellent choice as long as there is adequate protein in the base forage. For a lactating cow, as long as the base forage contains 10.5 to 11 percent protein, citrus pulp makes an excellent choice; however, if the hay contains less than 10.5 percent protein, a supplement with greater protein concentration will be needed.

Beet pulp. Beet pulp is produced after the extraction of sugars from sugar beets. Beet pulp can range in energy from 60 to 70 percent TDN and 10 percent protein but is low in indigestible fiber. Depending on location, beet pulp may be available wet, dry, shredded, or pelleted. Beet pulp is commonly found in diets for horses and show stock but can be an adequate roughage replacement for brood cows and stockers if hay is scarce.

Brewers’ Grains

In Alabama, most of the brewers’ grains come from two breweries in Georgia and consist of spent barley malt. The product is wet with about 20 to 25 percent dry matter. First, it is important to realize that for each 24-ton load of wet brewers’ grains purchased, 18 tons of water and 6 tons of feed are on the truck. If the price is $20 per ton, the price on a dry basis is $80 per ton.

Shelf life is a general concern when using any wet feed. Wet brewer’s grain needs to be stored under anaerobic conditions for best results, although it can be stacked in an open bay if it is to be fed rapidly, especially during the winter months. Free-choice–fed 600-pound weaned calves consumed 24 pounds per day (6.2 pounds of dry matter) while grazing bermudagrass pastures and had gains of 1.56 pounds per day for 45 days postweaning. The bottom line is that its usefulness is limited because of the high water content.

Other Byproducts

In some cases, a producer may have the opportunity to use unique byproducts specific to their area. For instance, producers located near a snack manufacturer or food processing plant may be able to use broken chips. Other items such as vegetable or fruit poultice and some expired ingredients such as bread and candy can be used in a complete ration.

However, because data regarding the nutritional information of these ingredients is limited, work with your local Extension agent or specialist to submit a sample for feed analysis. Because these ingredients may be high in salt or sugars, feed them in small amounts.

Feed Value

Comparing various byproduct feeds to a sole corn price and assessing their relative worth is a challenging task. This becomes more manageable when solely focusing on their energy value (measured by TDN content). Yet, if both energy and protein are taken into account, the analysis grows notably intricate. To facilitate comparisons between different feedstuffs and byproducts, it is imperative to establish their dry matter value. When you compare feedstuffs using their dry matter content, it reduces the substantial variability caused by differences in moisture content. Once you’ve pinpointed the lacking components in a herd’s existing diet through forage and hay testing (be it energy or protein), you can easily compare various feed options by assessing their cost per pound of nutrients.

For example, a fall calving herd consuming bahiagrass hay will be limited on energy going into winter. Current price and nutritive value of three byproducts are as follows:

- Dried distillers’ grains ($250/ton) = 89% DM, 89% TDN

- Soyhulls ($163/ton) = 90% DM, 63% TDN

- Corn gluten feed, wet ($86/ton) = 44% DM, 85% TDN

First, determine the pounds of nutrient available per ton:

- Dried distillers’ grains = 2,000 lb. x 89% DM x 89% TDN = 1,584 lb. TDN/ton

- Soyhulls = 2,000 lb. x 90% DM x 63% TDN = 1,134- lb. TDN/ton

- Corn gluten feed, wet = 2,000 lb. x 44% DM x 85% TDN = 748 lb. TDN/ton

Next, evaluate price per pound of nutrient:

- Dried distillers’ grains = $250/ton/1,584 lb. TDN = $0.16/lb. TDN

- Soyhulls = $163/ton/1,531 lb. TDN = $0.14/lb. TDN

- Corn gluten feed, wet = $86/ton/748 lb. TDN = $0.11/ lb. TDN

Kim Mullenix, Beef Cattle Systems Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor, and Micayla West, Graduate Research Assistant, both in Animal Sciences, Auburn University, and Darrell L. Rankins Jr., former Extension Animal Scientist.

Kim Mullenix, Beef Cattle Systems Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor, and Micayla West, Graduate Research Assistant, both in Animal Sciences, Auburn University, and Darrell L. Rankins Jr., former Extension Animal Scientist.

Revised August 2023, Byproduct Feeds for Alabama Beef Cattle Operations, ANR-1237