Forestry

Climate-smart forestry (CSF) is a natural solution to combat the rise of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere by storing carbon in trees and wood products. To better recognize why CSF and storing carbon is important, we must first understand what carbon is, why it needs to be stored, and why using forests is one of the most pragmatic choices.

Carbon Sources & Sinks

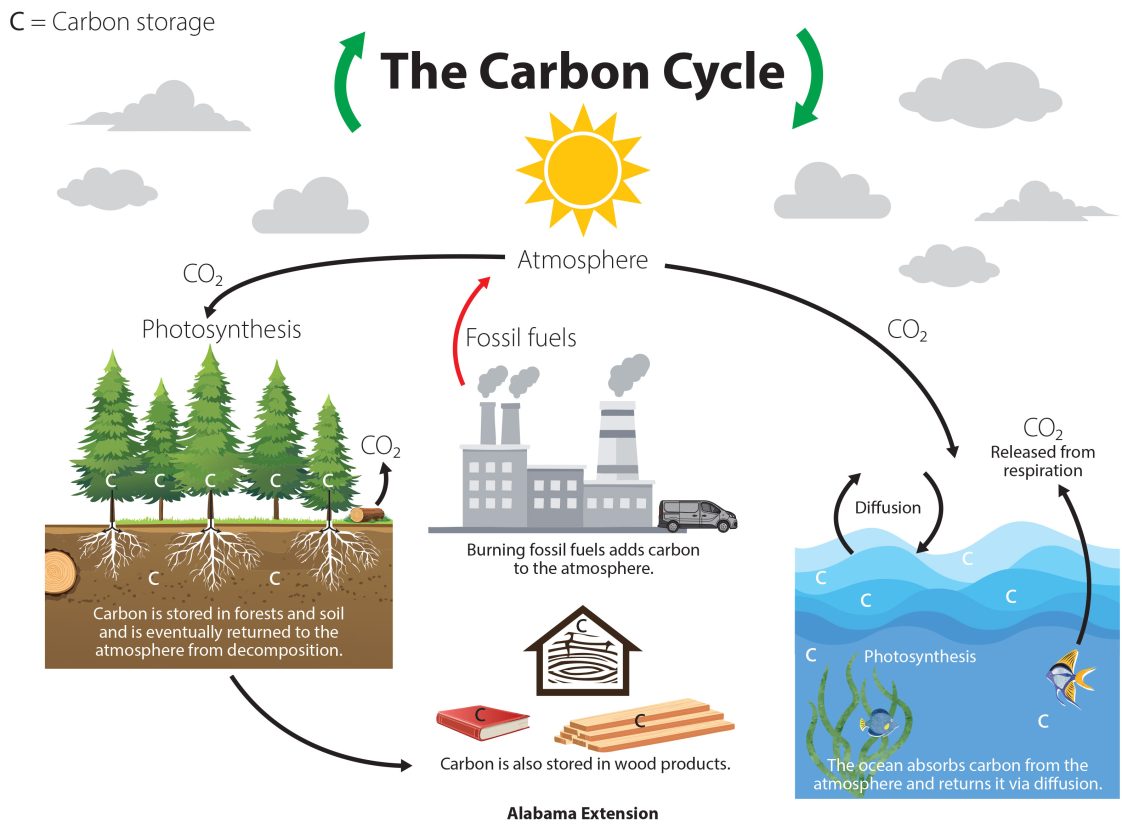

Figure 1. The carbon cycle is the natural process in which carbon moves throughout earth’s atmosphere, land, and ocean.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a naturally occurring chemical compound with its own life cycle (figure 1). CO2 naturally moves throughout various environments and, until recently, has generally been well regulated by this cycle. This change is because the natural carbon cycle has experienced an influx of atmospheric carbon dioxide globally for the past few centuries. This excess of CO2 results from burning fossil fuels through land use change, electricity, transportation, and industry. The rapid increase in atmospheric CO2 has caused a disparity in the carbon cycle, resulting in an imbalance in the carbon exchange between our atmosphere and carbon sinks (oceans, rocks, soil, forests, plants, and wildlife). This disparity is one of the contributing factors to increasing temperatures and a more variable global climate. One way to offset some of the overabundance of CO2 is by ensuring that our carbon sinks are in optimal condition. Carbon sinks work by absorbing and storing carbon.

Forests as Carbon Sinks

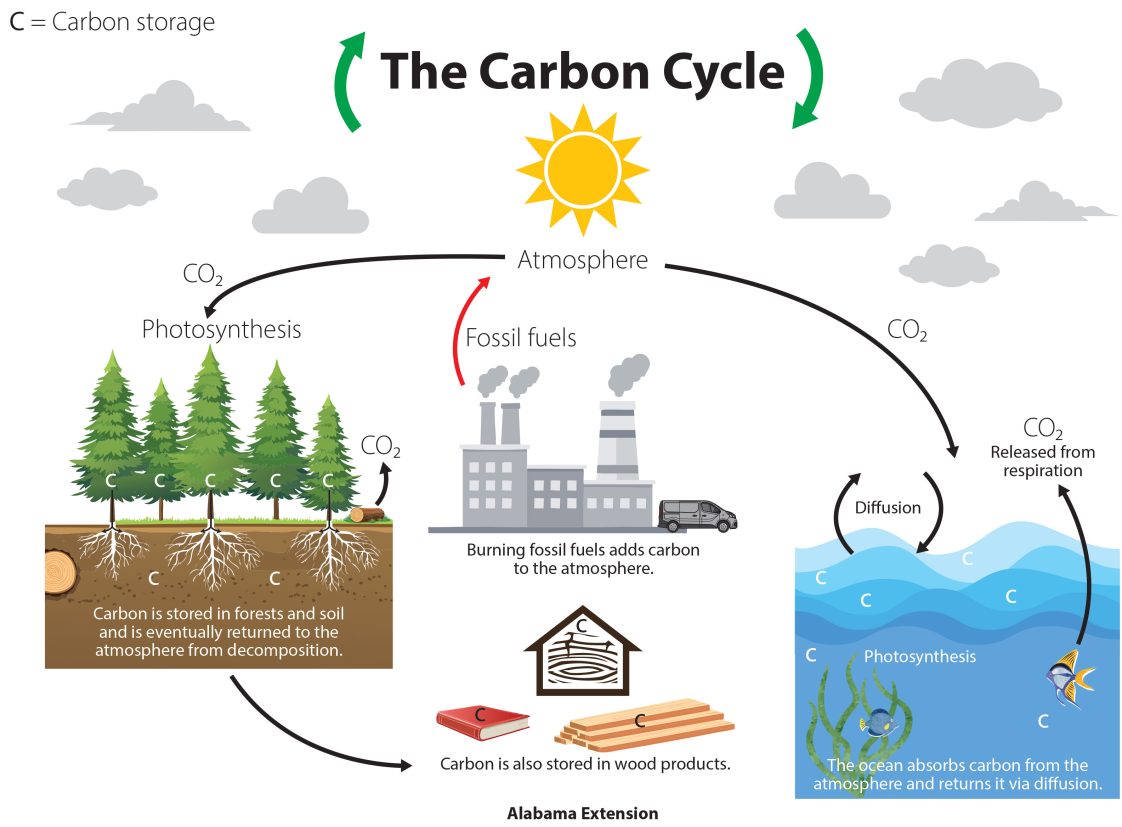

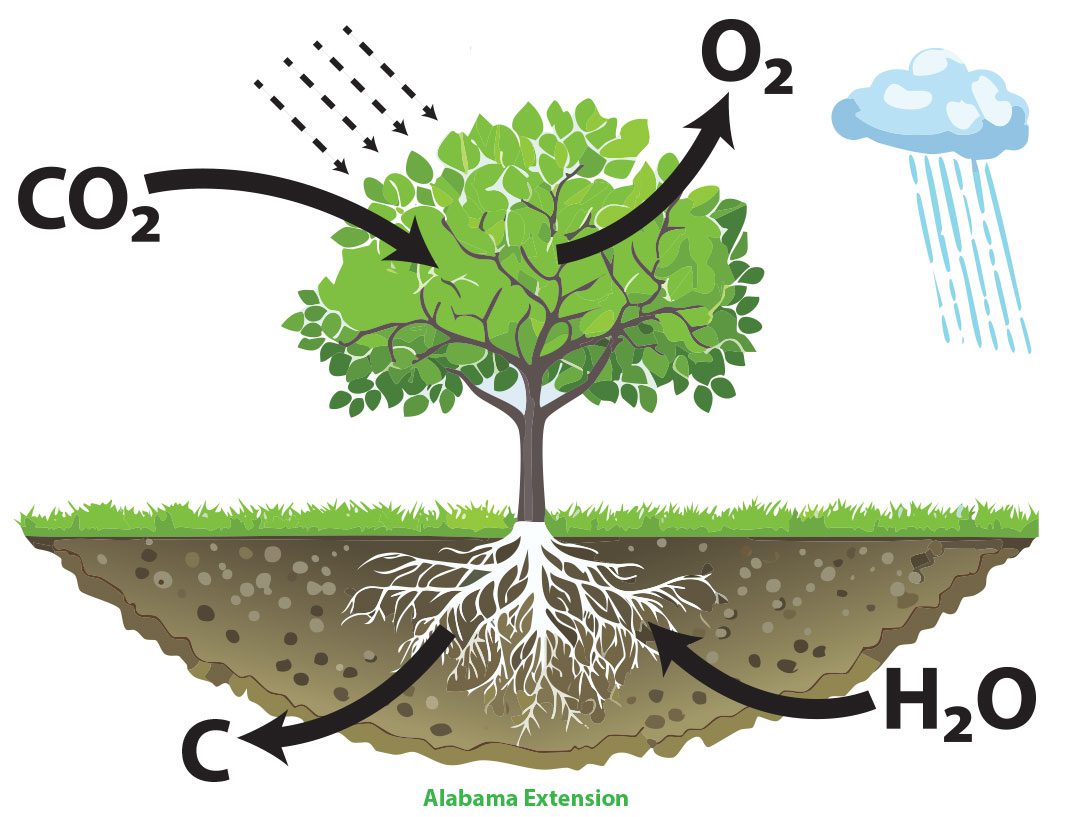

One of the most effective ways to store CO2 is also one of the few carbon sinks humans can directly influence: forests. Forests globally absorb about twice as much carbon as they emit each year. The 800 million acres of United States forests alone reduce global CO2 levels by approximately 13 percent; of that, 33 percent (one-third) is from the 214 million acres that comprise the southeastern forests. Furthermore, 80 percent of those forests in the southeast are privately owned. Trees work to store—or sequester—carbon as long as they are actively growing and producing wood. Like most plants, trees utilize the process of photosynthesis, which drives the removal of atmospheric CO2. The trees gain energy from the sun, converting CO2 and water into sugar that the plant can use as “food” (figure 2).

Figure 2. Photosynthesis is a physiological process in which sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water create energy for trees

When a tree dies, some stored carbon returns to the atmosphere from decomposition, but the majority will return to the soil. To extend the time carbon is stored and avoid admission to the atmosphere or soil, trees can be harvested and made into long-lasting wood products, such as lumber, furniture, pallets, and other wood products. The carbon will remain stored until these products are degraded (burned, left to decompose, etc.). Carbon can be stored within trees, soils, and durable wood products for centuries.

Storage Permanence, Mitigation Potential & Our Options

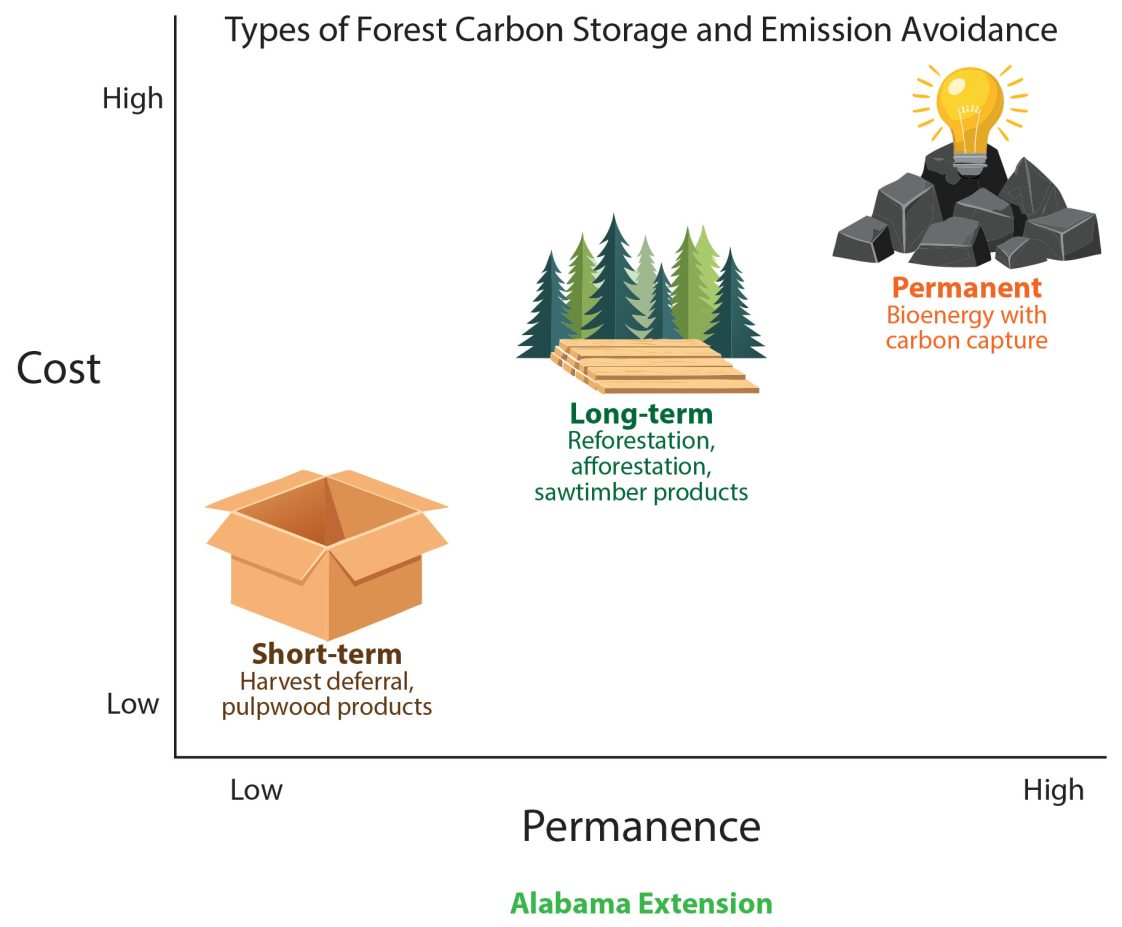

Understanding how trees can store carbon and the different carbon storage options is important—understanding storage options aids in making informed management decisions and harvesting and reforestation practices. Each storage option varies in its permanence, mitigation potential, and cost. Generally, focusing on those options with the highest mitigation potential and longest permanence is ideal. However, the cost and feasibility of each of these options can be more advantageous in different scenarios. Storage permanence refers to the time that atmospheric carbon will be stored in woody products. The three levels of storage permanence are permanent, long-term, and short-term (figure 3). Although each is an option for mitigation, they are not equal.

Permanent solutions can hold atmospheric carbon for 100 or more years and avoid excess emissions. An excellent permanent solution could be biochar or woody bioenergy production with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Biochar is made by heating organic mass in high-temperature, low-oxygen conditions. This process results in the formation of solid black matter that can take up to a millennium to decompose completely. BECCS is the process in which biomass is burned and converted directly into usable energy with near-zero emissions.

Figure 3. Forest carbon storage options and emission avoidance vary in relation to permanence and cost.

Long-term solutions can store atmospheric carbon for at least 20 years. These options are less expensive and often more operationally feasible than permanent solutions. What classifies a solution as long-term is its relation to mitigation potential, permanence, and cost – typically lower when compared to permanent solutions. Options that fall into this category include reforestation, afforestation, and sawtimber products.

Short-term solutions can store atmospheric carbon for less than 20 years. These options are generally the least expensive and the most feasible. Options in this category include pulpwood products (paper, cardboard, and other fiber-based products) and harvest deferral (delaying harvest that results in an additional amount of carbon being sequestered beyond the baseline of the planned harvest). Recently, doubts have arisen about whether this option is as climate friendly as previously believed.

Choosing options with longer permanence can reduce atmospheric carbon from a cascade of carbon storage pathways. For example, when a pine plantation tree is harvested and utilized to create a long-term timber product, such as dimensional lumber, that carbon will be stored inside the lumber instead of being released into the atmosphere via decomposition or burning. The space where the trees were harvested will be replanted with new pine trees that will store carbon again. Finally, increased utilization of timber products helps lower the demand for alternative products that generate large amounts of atmospheric carbon during production.

Summary

Understanding how the carbon cycle works, the effect that increased atmospheric CO2 has on climate, and why trees are one of the most viable options for mitigation is essential in comprehending carbon storage. By leaning into CSF initiatives and the increased production of permanent and long-term storage options, we can pull carbon from the atmosphere and decrease the reliance on industry. For more information on climate-smart forestry, visit the Alabama Extension website at www.aces.edu. For more information on carbon tunnel vision, visit the IOPscience website.

Samantha Schweisthal, Graduate Research Assistant, and Adam Maggard, Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor, both in Forestry, Wildlife, and Environment, Auburn University; and Noah Shephard, Graduate Research Assistant, Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia.

Samantha Schweisthal, Graduate Research Assistant, and Adam Maggard, Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor, both in Forestry, Wildlife, and Environment, Auburn University; and Noah Shephard, Graduate Research Assistant, Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia.

New November 2024, Effective Climate-Smart Forestry: Carbon Cycle & Storage Options, FOR-2167