Forestry & Wildlife

Learn the techniques known to effectively identify, control, and remove nuisance populations.

Figure 1. Beaver cuttings are common when they are present—from cut saplings (left) to gnawed large trees (center) and even dock posts (right).

In the 1930s, beaver populations in Alabama were reduced to about 500 animals because of the demand for fur. Conservation efforts, such as reintroduction and regulated harvest, in conjunction with low fur prices that reduced trapping pressure, have resulted in an increased beaver population throughout the Southeast. In Alabama, beaver populations have come full circle, from the rare, occasional sighting to numbers that have created nuisance issues in some areas.

While the reproductive potential for beavers is relatively low compared to most other rodents, populations continue to expand due to their territorial behavior and constant colonizing of new areas.

Beavers mature at the age of 2 or 3 years and have yearly litters that average just two or three young, called kits. In late winter or early spring, parents force out juveniles, which travel 1 to 3½ miles in search of suitable territory. Depending on the region and quality of habitat, beavers reside in colonies averaging four to eight individuals, with home ranges of 20 to 40 acres. A breeding pair that is left uncontrolled can have dramatic impacts in a short time.

For some landowners, beavers create damage through flooding and cutting of timber, crops, ornamental plants, and even buildings. In constructed ponds, beaver dens often damage the dam, creating erosion, collapses, and leaks; their presence should not be tolerated or the pond could be lost.

Despite these damages, the presence of beavers is not always detrimental. The beaver’s return has generally been beneficial to water quality and wildlife. The wetlands they create provide nutrient uptake and trap sediments, improving water quality and decreasing runoff. The altered stream flow and open forest canopies foster a habitat that generates a tremendous diversity of plants and animals that has even aided in the return of the wood duck from near extinction.

Figure 2. Dams (left), lodges (center), and clogged culverts (right) constructed from cut limbs and mud are signs of beaver presence.

If landowners are willing to tolerate some timber loss caused by flooding and cutting, the backwater and ponds that beavers create can be excellent for wildlife and can serve as areas to duck hunt or fish.

If beaver activity is problematic, beavers should be controlled as soon as possible to help minimize damage and losses.

Damage Identification and Signs

Signs of beaver presence include girdled or downed timber (figure 1); dams, lodges, and clogged culverts consisting of cut limbs and mud (figure 2); bank dens; flooded timber, fields, and roads; cut crops; stripped limbs; slides; crossovers; castor mounds; and tracks. Muskrats and otters can create signs similar to beavers. Understanding the differences is important towards identifying what species are present and require control.

Figure 3. Excluding beaver access to culverts, drains, and spillways is a good damage-prevention practice. Installations can be simple, with metal posts and fencing used (top), or complex, with multiple fences and piping (bottom). Most any exclusion will require monitoring and maintenance to ensure they stay cleared. (Credit: USDA-APHIS Wildlife Services)

Both muskrats and otters create slides and runs and use bank dens. Muskrats also will create small lodges using cattails and vegetation (unlike beavers that use cut limbs and mud), and they stockpile smaller cuttings of vegetation in a feed bed. Muskrats will not produce the cut and stripped limbs nor the large, wide basketball-wide runs and entrances to bank dens that are made by beavers. Unlike beavers and muskrats, otters are carnivorous and do not damage or feed on vegetation. Instead they leave behind shells of mussels they feed on and scat filled with fish scales and bones in areas they frequent. If unsure of the species present, consider installing trail cameras in areas of high use or sending photographs to a biologist for determination.

Control Techniques

The most prudent approaches to controlling beaver damage are exclusion and lethal control by trapping and shooting.

Exclusion

Metal fencing and barriers effectively prevent and exclude beavers from accessing or damaging valuable trees and other resources. These structures can be used temporarily to prevent damage while beavers are being removed, or they can be installed permanently.

It is important to wrap individual tree barriers at least 3 feet in height; beavers will stand on their back legs to gnaw. Do not tightly wrap trees; beavers may chew through the fence mesh gaps. Looser wrapping also ensures that the trees still have room to grow and will not be damaged by metal mesh becoming embedded.

In some cases, beaver damage from clogging and flooding can be controlled by excluding beaver access to drains or outflows. There are many designs and strategies for excluding beavers from drainpipes, culverts, and spillways. These range from simple 6 × 6 inch metal mesh fencing to complex installations with multiple fences, inlets, and piping (figure 3). Use only metal posts with exclusion, as beavers will chew wooden posts.

Regardless of the exclusion used, these areas still require maintenance and cleaning, as they can accumulate debris. Beavers also may try to stop the flow of running water around the fences or even try to incorporate the fencing into a dam.

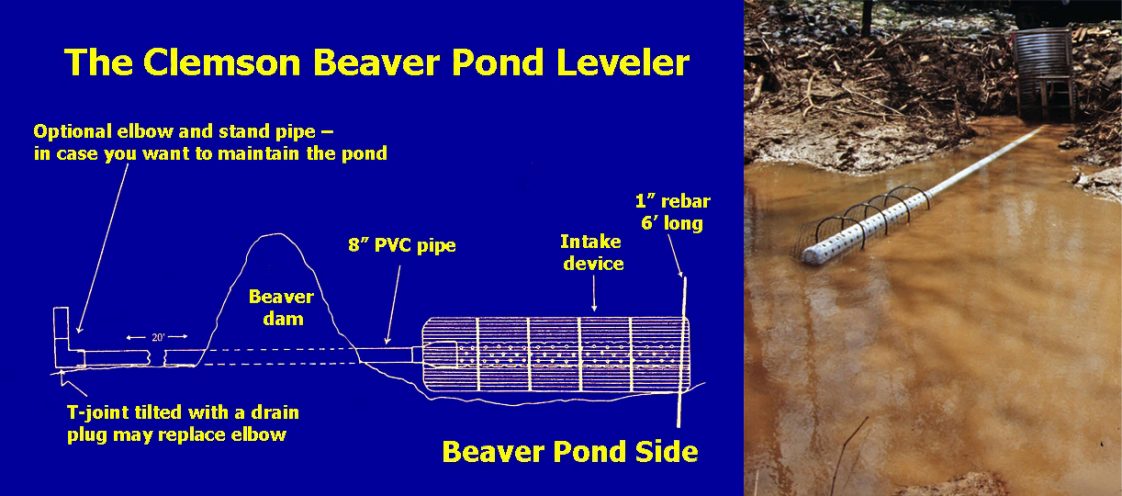

A pond-leveling device, such as the Clemson Beaver Pond Leveler, allows the manager, rather than the beavers, to control the water level (figure 4). The ability to manually raise or lower water levels in a pond or backwater is helpful if the landowner wishes to manage the area for other wildlife, such as waterfowl, or just maintain water levels in the presence of beavers. These devices are placed through the dam to manipulate or maintain water levels; however, if beavers are abundant, they may attempt to stop up these drains and reduce the water flow, so they must be monitored and cleaned regularly.

Figure 4. Water control devices, such as the Clemson Beaver Pond Leveler, enable managers to manipulate water levels in the presence of beavers.

Trapping

Trapping is an effective means of reducing beaver populations that has been used throughout the history and range of the beaver. From the recreational aspects of trapping to the fur and edible meat they provide, beavers are well suited for population control through trapper harvest. This approach promotes the use of nuisance populations as a renewable resource rather than strictly as pests to be controlled.

Trap selection, sets, and equipment required will vary based on the area being trapped. Prior to trapping there are several questions you must answer to determine effectiveness and personal ability. First, do you have access to the areas where beavers reside? If not, request permission from the landowner(s). Surrounding landowners may be glad to allow access for beaver control, because they are likely experiencing the same damage issues.

Figure 5. Common beaver trapping equipment

Consider enlisting as many neighboring properties as possible. Trapping and cooperation among surrounding landowners will result in more effective and longer-lasting beaver damage control. Sharing the cost of equipment and duties of setting and running traplines can reduce the individual costs of control, as the gasoline and time saved by sharing duties can be tremendous.

Another important consideration is safety and nontarget catches. For example, is human safety, primarily children, an issue? Are the neighborhood pets at risk? Do you have otter or muskrats using the property? As a trapper, you are liable for any damages and nontarget catches that occur from the traps you set.

The final considerations are the physical ability, skill, and time required to be an effective and humane trapper. Like any outdoor endeavor, trapping and processing beavers (or any fur bearer) comes with a learning curve. Consult an experienced trapper or take advantage of resources that can help you become an ethical, effective trapper. Consider Alabama Extension, state fish and game agencies, national and state trapping associations, and numerous internet forums and online videos (ACES YouTube Beaver Trapping Series at www.aces.edu/go/489).

Beginning trappers, regardless of the trap type or set used, should remember to be patient and persistent. Sometimes beavers can be captured in just the first few days of a set; other times it may take weeks. There is a great difference between effective trapping and efficient trapping—efficiency usually can be improved only with time and experience in the field. Trapping in the areas beavers use is also a physical demand. Be sure you are capable of traversing through mud, deep water, and brush, all while wearing waders and carrying equipment in variable weather conditions.

Figure 6. A body-grip trap placed in a run (top) is a high-percentage set for an effective beaver catch (bottom).

Anyone considering trapping beavers should have, at minimum, boots or waders, a small hatchet, a roll of 11- or 14-gauge wire, lineman pliers, a variety of 18-to-30-inch stakes, a pack or bucket in which to carry it all, and traps suited to needs (figure 5). Setting tongs for body-gripping traps are also considered a must by most trappers; they are helpful for setting and removing beavers from traps. Additionally, a heavy garden or potato rake is often carried to rake debris and breach dams for trap sets. Trap supplies are available at local farm and sporting goods stores and many online vendors.

Alabama law requires that all trappers carry a restraint pole to safely remove nontarget catches from traps and that all traps be tagged with the trapper’s name and address. To ensure as little stress on trapped animals as possible and to preserve pelt quality, state regulation requires that land sets be checked every 24 hours and water sets be checked every 72 hours.

A trapping license is not required for trapping nuisance beavers, but written permission from the landowner should be obtained. A license is required if beaver pelts are to be processed and sold. However, trapping regulations can change from year to year, so be sure to reference the state’s most recent regulations.

Body-Grip Traps

Body-grip traps, which kill the beaver within a few seconds of entering the trap, are ethical. These traps vary widely in size, the 8 × 10 inch body-grip trap, known as size 330, is commonly used for southern beavers. Because of their potential danger to humans and domestic animals, this size and style of trap is one of the most dangerous and difficult to set without proper training and practice. Alabama law requires that body-grip traps with a spread exceeding 5 inches be set only in water.

Body-grip traps are versatile and highly adaptable for both shallow and deep water. They can be set in many different configurations on a variety of travel areas. They are especially effective placed at the entrances of dens and lodges and at most crossovers, culverts, and any other restriction that concentrates beaver travel. A common set involves placing the trap immediately above or below a beaver dam at an active crossing.

Figure 7. A drown slide setup using a number 5 coil spring foothold trap (top) and an effective front foot catch (below).

Another productive set is body-grip traps placed in shallow runways between dams, bank dens, lodges, and feeding areas as beavers travel back and forth (figure 6). If beavers are active, these runs are usually visible and easy to locate, as they will be clear of debris and often down to slick mud.

Many times, beavers may be trapped close to the water’s surface. In such cases, the trap should be positioned with the top of the trap 2 to 3 inches above the surface, with the trigger mechanism beneath the water and the prongs sticking upward.

In some instances, it may be necessary to modify trap positions for deeper sets, such as deeper den entrances. Dive sets can be made by placing a stick across the surface of the water above the trap. This forces the beaver to dive under the stick and through the trap. Scent mound sets using beaver castor as a scent lure can be used at sites where beavers are crawling out of the water to cut timber, crops, etc.

Foothold Traps

Foothold traps are useful in some situations, particularly if a beaver is trap shy and avoids body-grip traps, or where nontarget safety concerns limit use of a body-grip trap.

Foothold traps with an inside jaw spread of 6 to 7 inches (sizes 3 to 5) can be used where beavers exit the water or make dam repairs. These traps can be set to drown the beaver after it is captured.

An ethical and effective drowning set requires a cable staked taut at the shoreline with a drown slide that can access 3 feet of water and is anchored by at least 30 pounds. A foothold is attached to a drown lock and placed just beneath the water’s edge for a front foot catch or deeper for a hind foot catch (figure 7).

Figure 8. A snare set at the entrance of a bank den

Snares

Snaring is another useful form of beaver trapping and can be used in many of the same situations as body-grip traps, such as in a run, in a dive set, at a den entrance (figure 8), or in a scent mound.

As with large body-grip traps, Alabama law requires that snares be set in the water. Some trappers prefer snares over body-grip traps for several reasons: snares are significantly lighter and easier to transport; they are safer to humans and pets; and, in some sets, nontarget animals may be released unharmed. Snares can be set so that they drown the beaver, or they may be set to simply catch and hold the animal until the trapper returns; this requires the trapper to check the trapline daily.

Securing Traps

Regardless of the trap type used or where the set is made, all traps must be sufficiently secured so that the captured animal cannot escape, be injured, or otherwise suffer.

Proper staking varies based on soil composition. Stakes 30 inches or longer are often required for sets in loose, sandy, or flooded soils. Shorter 18-to-24-inch stakes may be sufficient in drier, more compact soils, such as clay or loams. Some soils may be too moist, loose, or rocky, making staking not an option. Instead, traps must be cabled or wired to trees or rocks or placed on a drag.

With sets in or near streams subject to high runoff, run a piece of wire from the trap ring to a substantial tie on either bank, preferably downstream. This arrangement will prevent the loss of traps during high water and may prevent the loss of a trap and beaver to predators and feral dogs. Sufficient swiveling is also important so that traps do not bind or cause injury to captured animals or give them leverage to escape—especially important when using footholds and snares.

Shooting

Shooting may be an effective means of beaver control in ponds and lakes with small or infrequent beaver populations. A 12-gauge shotgun with number 4 buckshot or BB shot is a good choice over rifles, which increase the risk of dangerous ricochets. Remember, shooting will often render the pelt worthless.

Using red cellophane to cover light sources used to locate beavers at night will not frighten the animal and will provide more time for an effective and ethical shot. If beavers are to be shot at night, special permission must be obtained from the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources District Office.

Dam Removal

Water backed behind a beaver dam may limit property access and place standing timber or crops under stress; this may reduce productivity or ultimately kill them. If a dam is torn away while beavers are still in the area, they often make quick repairs resulting in continued flooding damage.

Trapping beavers in conjunction with removing the dam will reduce the damage. Depending on the situation, it may be best to leave the dam intact until all the beavers are trapped from an area, then break or remove the dam. Partial removal of the dam often attracts beavers to the running water, offering a good place to set a trap as they return to repair the broken dam.

When trapping concludes and the dam is ready to be cleared, several options exist. The final decision depends on the goals of the landowner, the size of the dam, and economics. If the dam is small, heavy rakes and axes may be sufficient for tearing out a hole to allow water to drain. Larger dams may require the use of heavy equipment or explosives to move the large volume of sticks, mud, and other debris from the dam. Explosives can be dangerous and are subject to state and federal regulations. If a dam requires explosives, contact the United States Department of Agriculture, Animal Plant and Health Inspection Service: Wildlife Services for more information.

Revised by Norm Haley, Extension Agent; ACES-AFNR-Field, Forestry, Wildlife, and Natural Resources, Auburn University. Originally written by James Armstrong, former Extension Specialist, and Norm Haley, Extension Agent, ACES-AFNR-Field, both in Forestry, Wildlife, and Natural Resources, Auburn University.

Revised by Norm Haley, Extension Agent; ACES-AFNR-Field, Forestry, Wildlife, and Natural Resources, Auburn University. Originally written by James Armstrong, former Extension Specialist, and Norm Haley, Extension Agent, ACES-AFNR-Field, both in Forestry, Wildlife, and Natural Resources, Auburn University.

Revision August 2025, Beaver Damage Control and Trapping in Alabama, ANR-0630