Home & Family

What is a tick, why do ticks bite, and why does it matter?

Ticks are very small external parasites that feed by sucking blood from animals (hosts), including mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Most ticks go through four life stages: egg, six-legged larva, eight-legged nymph, and adult. After hatching from eggs, ticks must consume blood at every stage to survive, and most ticks prefer a different host at each life stage.

In Alabama, there are several tick species, some of which carry illness-causing bacteria that can be transferred to the hosts on which they feed. While we do not know the percentage of infected ticks in Alabama, we do know that many people become ill from them every year.

All people who spend time outdoors, either in their backyard or the wilderness, are at risk of exposure to ticks and contracting a tick-borne illness. Hikers, hunters, outdoor workers, and other groups are more likely to be bitten by ticks because their activities usually take place in prime tick habitat. Horses, dogs, cats, and other pets that spend time outdoors can be bitten by ticks and infected with a tick- borne illness. If those pets come inside, they can bring ticks into your home and put you at greater risk of being bitten.

Figure 1. Lone star tick (a), black-legged tick (b), American dog tick (c)

What species of ticks are found in Alabama, and what hosts do they bite?

The lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum, is the most abundant tick species in Alabama. Adult females are easily identified by a single white dot in the center of their brown bodies, the feature that lends to their name. Lone star ticks aggressively seek human and pet hosts and may transmit disease.

The black-legged tick, Ixodes scapularis, is an abundant tick species in Alabama. This species is also known as the deer tick. This name should not be interpreted as meaning that it only feeds on deer or is the only tick species found on deer. A reddish-brown body distinguishes adult females of this species. Black-legged ticks will readily attach to humans and pets and may transmit disease.

The American dog tick,Dermacentor variabilis, is an abundant tick species in Alabama. Adults of this species commonly attach to human and pet hosts and may transmit disease.

The brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, is found throughout Alabama and commonly infests homes, animal pens, and dog kennels. They can spend their entire life cycle indoors. Controlling infestation in a home can be difficult once this species is established. Brown dog ticks prefer dogs, but will feed on humans and other mammals. They may transmit disease.

The Gulf Coast tick, Amblyomma maculatum, is found in Alabama and looks similar to the American dog tick. The species prefers to feed on large hosts such as livestock, deer, and coyotes. Gulf Cost ticks may attach to humans and pets if given the opportunity and may transmit disease.\

Figure 2. Brown dog tick (a), Gulf Coast tick (b) Photos courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, James Gathany

How do ticks find and stay attached to hosts?

Ticks find their hosts by sensing animals’ breath, odor, heat, vibrations, or shadows. They also can find hosts by waiting, or “questing,” on the tips of grasses and shrubs along a well-used path. Ticks cannot fly or jump; but when hosts brush past, ticks can quickly climb onto their clothing or fur.

When a tick finds a prime location on a host, it cuts into the skin, inserts its feeding tube (hypostome), and begins feeding.

What happens when ticks are attached?

Figure 3. Spotted fever rash. Photo courtesy of the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention

During feeding, a tick will slowly suck its host’s blood for several days. If the tick contains an infectious organism (pathogen), it could be transmitted to the host during this time. At its next feeding, an infected tick can transmit pathogens to a new host, potentially causing illness.

What illnesses can ticks cause?

Spotted fever. This illness caused by the spotted fever group ofRickettsia bacteria is the most commonly reported tick-borne illness in Alabama. The best known and most severe form of the illness is Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Symptoms begin to present in a few days to 2 weeks after infection and include fever, headache, muscle pain, lack of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Most people develop a spotted red rash, typically around the wrists and ankles at first. This rash can spread to the entire body (figure 3).

Spotted fever infections are treated with antibiotics. These illnesses, like Lyme disease, are difficult to diagnose because of their nonspecific symptoms. This is particularly true when the rash is absent, which happens in approximately 10 percent of cases. These infections can cause lifelong health problems or be fatal if not treated quickly. Dogs may also get spotted fever infections if bitten by an infected tick.

Lyme disease. This is the most commonly reported vector-borne illness for humans in the United States, with approximately 300,000 cases reported per year. Over the past 10 years, the Southeast has experienced a tremendous increase in the number of reported cases.

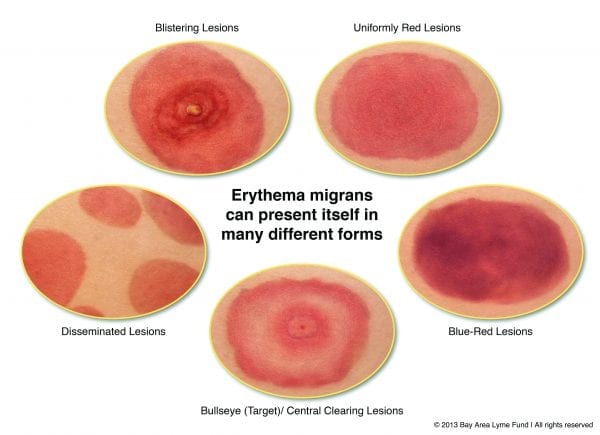

Typical symptoms appear within days or weeks after being bitten by an infected tick and may include fever, headache, chills, stiff neck, fatigue, mental fogginess, depression, swollen lymph nodes, muscle aches, and joint pain. A telltale sign of Lyme disease is an expanding red skin rash (figure 4), called erythema migrans, located anywhere on the body. This rash may have a central area of clearing, giving it a “bull’s-eye” appearance (figure 5). Most, but not all, of those infected present a rash, but the rash may not be at the location of the bite.

Figure 4. Rashes caused by Lyme disease. Photo courtesy of the Bay Area Lyme Disease Foundation.

Figure 5. Bulls-eye rash caused by Lyme disease and STARI

Photo courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Lyme disease is treated with antibiotics. If caught early enough, recovery is usually quick. If treatment is not immediately received, infection can spread to other parts of the body, and cause serious chronic medical issues.

Because Lyme disease can be mistaken for other illnesses, such as arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, ALS, fibromyalgia, mental illnesses, and more, it is important to watch for other symptoms and educate yourself. Remember, too, that horses and dogs can acquire this disease from tick bites.

Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI). STARI, also known as Masters disease, is an emerging tick-borne illness found particularly in the South. While symptoms are similar to Lyme disease, not much is known about its cause or long-term effects. Symptoms occur within approximately 7 days of infection and include fatigue, fever, headache, and muscle and joint pain. A red bull’s-eye rash may form on the skin at the location of the bite. Antibiotics are used in treatment.

Ehrlichiosis. This is another emerging tick-borne illness that is more common in the South, particularly in dogs. Symptoms commonly occur within 5 to 10 days of infection and may include fever, headache, muscle ache, lethargy, confusion, nausea, and vomiting. Less than 30 percent of infected adults develop a body rash. Serious, lifelong illness and possible fatality can occur if antibiotic treatment is not administered quickly.

Anaplasmosis. Symptoms typically occur within 1 to 2 weeks after a bite from an infected tick and include fever, headache, lethargy, chills, cough, nausea, abdominal pain, muscle pain, and confusion. A rash is rare with anaplasmosis infection. Early antibiotic treatment can be successful, but long-term complications and death are possible.

Babesiosis. Unlike other tick-borne illnesses in Alabama, babesiosis is not bacterial, so it does not respond to antibiotics. It is caused by a parasite that infects red blood cells, much like the parasite that causes malaria. Symptoms may never develop in some people. Others may develop fever, chills, sweats, headache, body aches, loss of appetite, nausea, fatigue, and anemia. If not treated early, problems can become severe and cause fatality. Dogs may become infected with babesiosis as well.

Tularemia. This is caused by a bacterium transmitted by ticks and deer flies, or by handling an infected animal’s carcass such as when skinning a rabbit without gloves. (Rabbits are common carriers of this disease.) Symptoms appear within 3 to 5 days after being bitten and include chills, headache, muscle aches, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and swollen lymph nodes. Skin ulcers also may develop; they occur in about 80 percent of cases. It is not uncommon for symptoms to disappear for 1 to 3 days and return for 2 to 3 weeks. This disease can be fatal but is successfully treated with antibiotics if diagnosed early.

Figure 6. Lone star tick (a) Photo courtesy of Gerald Homes, California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo, Bugwood.org. Tick attached to skin (b)

Tick paralysis. This is one of a few tick-borne conditions not caused by a pathogen. The illness is caused by a neurotoxin produced in a female tick’s salivary glands and transmitted during attachment and feeding. Symptoms usually occur within 2 to 7 days and include headache, vomiting, fatigue, and loss of muscle function. Treatment requires removal of the tick, after which symptoms go away within hours to days. If untreated, it can lead to respiratory failure and death. Children in rural areas during the spring, especially those not checked around the neck, scalp, and other areas upon coming indoors, are at greatest risk of getting tick paralysis.

Alpha-gal allergy. Also known as the red meat allergy, this is an emerging illness in the Southeast, and like tick paralysis, is not caused by a pathogen. This allergy is induced in some people when the saliva of an attached lone star tick causes the immune system to produce antibodies specific to alpha-gal—a carbohydrate found in red mammalian meat. After this occurs, when a person eats red meat, the meat triggers an allergic response within 4 to 6 hours of ingestion. Symptoms include upset stomach, diarrhea, hives, itching, and anaphylaxis. A blood test confirms the condition, and avoiding red meat is the only treatment.

These are not exhaustive descriptions of each illness, and there are other tick-borne illnesses you and your pets could be infected with. You should further educate yourself on the characteristics and symptoms of them all. Be aware of how you feel if you are at risk of coming into contact with ticks. Individuals that acquire these diseases may not develop all the symptoms listed, and the number and combination of symptoms can vary greatly from person to person.

Having more than one illness at a time, or co-infection, also is possible. See a doctor immediately if you suspect infection. The “wait and see” approach could be very harmful to you. Many tick-borne illnesses are successfully treated if symptoms are recognized during the early stages of infection.

When the illness is not diagnosed early, treatment can be difficult, and chronic symptoms may develop. Education is key to preventing lifelong illness.

Pets are at risk of becoming infected with some of these illnesses. If your pet spends time outdoors, check them regularly for ticks and be on the lookout for signs of lethargy, arthritis, lameness, fever, fatigue and change in appetite. Because illness is more difficult to detect in pets, it is important to closely watch their behavior. See a veterinarian immediately if you have reason to believe they are infected.

When are ticks active and which illnesses do they transmit?

Because of the warm, southern climate, ticks in all life stages may be active year-round in Alabama. The table on page 5 shows when each tick species is most active throughout the year and what illnesses they have the ability to transmit.

Where can you be exposed to ticks?

Ticks are commonly found in the following habitats:

- tall grasses and prairies

- shrubs and brush

- low-lying branches

- leaf litter

- rotten logs or stumps

- wooded areas and their edges

- moist/humid areas

- beaches and dunes

- areas of lawn adjacent to woods or fields

- stone walls and woodpiles where small mammals live

Be on the lookout for brown dog ticks on your pets and in your home, furniture, animal pens, and dog kennels.

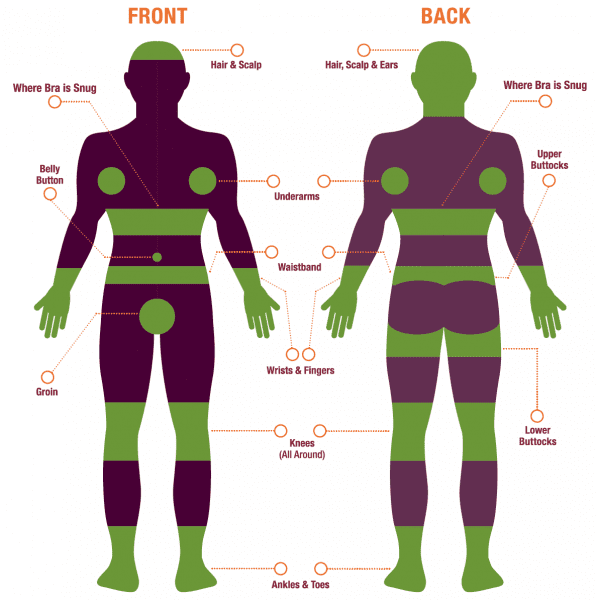

Where are the most common places to find ticks attached on the body?

Figure 7. Tick on a dog

Immediately after coming in from outside, you should check yourself, significant others, and pets for ticks over the entire body. Especially focus on dark, moist places that bend and fold:

- hair/scalp

- in and around ears

- under the arms

- inside belly button

- around waist under waistband

- groin area

- where bras pull snug to skin

- inside of thighs

- around the knees and ankles

- in between fingers and toes

For indoor/outdoor cats, check for ticks all over, particularly around the ears and eyes. For dogs, also check everywhere, especially around the face, ears, neck, armpits, thighs, belly, tail, and toes.

How is a tick properly removed from the body?

If you find an attached tick on yourself or your pet, remove it as soon as you can. The longer the tick is attached, the greater the chance it will transmit disease or cause illness. Proper removal is incredibly important, because improper removal can increase your risk of infection.

Figure 8. Tick tool and tweezers to properly remove ticks

To properly remove and dispose of a tick, grasp the tick as close to the skin as you can get with sterile tweezers or a tick tool (figure 8) and pull upward on the tick with a steady, even tug. After the tick is removed, wash and disinfect the area on the skin where the tick was attached. Wash your hands. Dispose of the tick by submersing it in rubbing alcohol for more than 1 day, wrapping it tightly in tape and throwing it away, or flushing it down the toilet.

These are the don’ts of tick removal:

- Don’t try to scrape off a tick.

- Don’t twist or squeeze the tick; this can cause the mouthparts to break off in the skin.

- Don’t burn a tick with a hot match while it is still attached.

- Don’t apply a substance such as nail polish remover, petroleum jelly, gasoline, or soap to the tick in an attempt to kill it while it is still attached.

- Don’t touch the tick with your fingers.

- Don’t wash the tick down a drain; it can crawl back up the drain and into your home.

| Tick Species | Months Active | Illnesses Transmitted |

|---|---|---|

| Lone Star | Nymphs and adults: March to October | alpha-gal allergy, ehrlichiosis, southern tick-associated rash illness, tick paralysis, tularemia |

| Black-legged | Nymphs: March to June, Adults:September to March | anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Lyme disease |

| American dog | Nymphs and adults: April to September | ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountian spotted fever, tick paralysis, tularemia |

| Brown dog | Nymphs and adults: all year | canine babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever |

| Gulf Coast | Nymphs: December to April, Adults: May to August | spotted fever rickettsiosis, tick paralysis |

How can tick encounters and bites be prevented?

There is currently no vaccination against Lyme disease or other tick- borne illnesses for humans.

It is incredibly important, therefore, to take preventative measures year-round when you are outside.

Follow these guidelines before going outside:

- Wear light-colored long pants and long-sleeved shirts. Tuck the shirt tail into the pants, and tuck the pants legs into socks.

- Put long hair in a bun or pull it up into a hat.

- Wear close-toed shoes.

- Use repellents that contain greater than 20 percent DEET on exposed skin and clothing.

- Treat clothing and gear with products containing 0.5 percent permethrin. This is the most effective preventative measure when used according to the label.

Follow these guidelines while outside:

- Walk along the center of a trail to avoid questing ticks at trail edges.

- Do not sit on rotten logs or stumps; that is where ticks seek refuge.

- Wear protective gloves when handling dead animals.

- Follow these guidelines immediately after coming indoors:

- Carefully examine clothing, gear, and pets. Ticks can ride into your home on something and attach later.

- Tumble clothes in a dryer on high heat for a half an hour to kill undiscovered ticks.

- Conduct a full body check in the shower or by using a partner or a mirror. You should do this for several days following potential exposure or make it part of your daily routine.

- Check skin for any bumps, scabs, or dirt specks that might indicate a tick, especially on the scalp. If you feel something, don’t squeeze or press it. Check it.

Follow these guidelines for pets:

- Use a brush to facilitate full body checks.

- Consult with your veterinarian for effective tick control products such as oral medication, impregnated collars, or topical treatments.

- Prevent tick-borne illnesses in your pets—this may also prevent illness in you!

Tick Danger Zones

Emily Merritt, Research Associate, School of Forestry & Wildlife Sciences, and Arnold Beau Brodbeck, Regional Extension Agent, Forestry, Wildlife and Natural Resource Management

Reviewed January 2024, Ticks & Tick-borne Illnesses in Alabama, ANR-2315