Home & Family

Young athletes must drink enough fluid to perform at their best and to reduce the dangerous risks of dehydration during prolonged physical activity.

Proper nutrition is fundamental to fitness and performance. Although many athletes carefully regulate their diet, they may pay little attention to their body’s fluid needs. They often misunderstand and, as a result, underplay the importance of water to good nutrition. Through normal perspiration, respiration, and urination, the body can lose up to half a gallon of water a day. Actively training athletes can lose even more! In addition, because young athletes are not as efficient at body temperature regulation as adults are, they risk overheating and the consequent onset of heat- related illnesses. It is imperative that young athletes drink enough fluid to perform at their best and to reduce the dangerous risks of dehydration during prolonged physical activity.

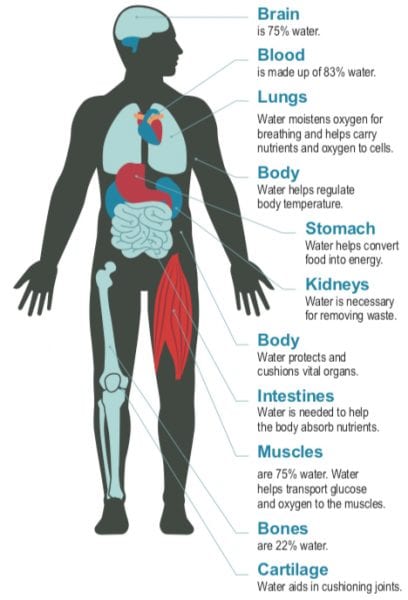

- Brain is 75% water.

- Blood is made up of 83% water.

- Lungs. Water moistens oxygen for breathing and helps carry nutrients and oxygen to cells.

- Body. Water helps regulate body temperature.

- Stomach. Water helps convert food into energy.

- Kidneys. Water is necessary for removing waste.

- Body. Water protects and cushions vital organs.

- Intestines. Water is needed to help the body absorb nutrients.

- Muscles are 75% water. Water helps transport glucose and oxygen to the muscles.

- Bones are 22% water.

- Cartilage. Water aids in cushioning joints.

Importance of Water in the Body

The body is comprised of about 60 percent water, and much of that water is located inside lean muscle tissue. Water is needed by the body because it regulates the processes and chemical reactions of every living cell.

If each cell is to complete the reactions demanded for performance at optimal speed, movement, and endurance, the body must have adequate access to fluid. Some of the functions of water:

- transporting protein, amino acids, carbohydrates, vitamins minerals, and oxygen to cells

- being part of the structure of the chemical compounds in the body

- aiding in the digestion and absorption of nutrients

- aiding in the repair and replacement of old tissues

- helping flush the system of toxic wastes

- helping to maintain constant body temperatures by providing perspiration for cooling and blood circulation for warming

- lubricating and cushioning the joints and tissues of the body

Water Balance

Water Input. Water needed by the body comes from a variety of sources and is provided by food, drink, and metabolism. In addition to water itself, beverages such as milk, sports drinks, and juices contain large amounts of water. Other foods also contain rich supplies of water. Fresh fruit and vegetables generally contain a lot of water (some contain as much as 95 percent water), while protein foods such as beef and eggs can contain up to 50 percent water. Water is also released in the body as foods are broken down and metabolized for energy.

Water Output. To ensure proper hydration, fluid lost must not exceed fluid consumed. The body can lose up to half a gallon of water a day through normal perspiration, respiration, and excretion processes. During prolonged physical activity, water losses increase due to increased breathing and sweating. In fact, during heavy exercise, an athlete can lose between 2 and 4 quarts of sweat (6 to 8 pounds of body weight) in just one hour! The body’s digestive system can only absorb about 1 quart of fluid per hour, so an athlete must consume fluids before, during, and after exercise to replace fluid losses and minimize dehydration.

Water Losses on Hot, Humid Days

High temperatures increase the rate of water lost through perspiration. Exercising in hot, humid climates presents yet another concern: the body’s ability to sweat efficiently is reduced because the sweat on the skin meets resistance evaporating.

The air is already filled with moisture, which makes it difficult for the sweat to evaporate. As a result, the body cannot cool itself properly, and internal body temperature can rise to dangerous levels.

Other factors can increase the rate of fluid loss. These must be avoided or minimized to stop the onset of rapid dehydration:

- excessive clothing, padding, and taping

- competing in environmental conditions to which the athlete is unaccustomed

- intense levels of solar radiation (bright sunshine)

- increased intensity of exercise

- increased duration of exercise

- failure to consume fluids every 15 to 20 minutes during practice (an athlete needs to drink even if he or she does not feel thirsty)

Athletes must consider these factors that increase the rate of fluid loss and use extreme caution when training on sunny, hot, and humid days. These combined factors present the most dangerous environmental conditions for athletes. They encourage the rapid onset of dehydration and quickly raise internal body temperature.

Effects of Dehydration

Dehydration is a net loss of water and fluids from the body caused by an imbalance in the body’s supply and demand. The first symptom of dehydration is fatigue. Other early symptoms include the following:

Dehydration is a net loss of water and fluids from the body caused by an imbalance in the body’s supply and demand. The first symptom of dehydration is fatigue. Other early symptoms include the following:

- thirst

- headache

- dry or “cotton” mouth

- dizziness or lightheadedness

- weakness

- rapid heartbeat

- dry, flushed skin

- muscle cramps

During physical activity, body heat rises very quickly due to the working muscles. One of the major functions of fluids is to maintain core body temperatures, so as body heat rises, the body compensates by sweating. As the sweat evaporates, the skin and the blood, which is traveling through vessels near the surface of the skin, are cooled. This cooled blood then flows back to the body’s core, thereby decreasing internal body temperature.

The body cannot properly cool itself when dehydration occurs. Serious heat-related injuries or illnesses, such as heat exhaustion and heat stroke, can result when excessive fluid is lost and not replaced during exercise and the body temperature increases. Symptoms of heat exhaustion include dizziness, weakness, rapid pulse, low blood pressure, headache, and elevated body temperature. Symptoms of heat stroke can include sudden cessation of sweating, clumsiness or stumbling, disorientation, vomiting, and loss of consciousness. Death can occur with heat stroke.

Dehydration reduces one’s endurance and increases one’s risk for heat-related illnesses, such as heat exhaustion and heat stroke. When the body becomes dehydrated, athletic performance can be greatly hindered. A water loss equal to 5 percent of body weight can reduce muscular work capacity by 20 to 30 percent.

Table 1. How Your Body Reacts When You Lose Fluids During Exercise

* With a 5 percent body weight loss, an athlete will need at least 5 hours to rehydrate.

This table presents a well accepted model for hydration before, during, and after exercise

| Percent Weight Loss | Effects on the Body |

|---|---|

| 1 to 2 | Increase in core body temperature |

| 3 | Significant increase in body temperature with aerobic exercise |

| 5* | Significant increase in body temperature with a definite decrease in aerobic ability and muscular endurance Possible 20 to 30 percent decrease in strength and anaerobic power Susceptibility to heat exhaustion |

| 6 | Muscle spasms, cramping |

| 10 or more | Excessively high core body temperature Susceptibility to heat stroke Heat injury and circulatory collapse with aerobic performance |

Monitoring Hydration

Thirst is not a good indicator of the need for water intake because exercise blunts the thirst mechanism. When thirst does become detectable, fluid stores have already been depleted, and the early stages of dehydration are apparent. At the point of thirst, the body has already lost up to 2 percent of its body weight in fluid, a loss which has been shown to impair thermoregulation and reduce work capacity by 10 to 15 percent.

Thirst is not a good indicator of the need for water intake because exercise blunts the thirst mechanism. When thirst does become detectable, fluid stores have already been depleted, and the early stages of dehydration are apparent. At the point of thirst, the body has already lost up to 2 percent of its body weight in fluid, a loss which has been shown to impair thermoregulation and reduce work capacity by 10 to 15 percent.

The color and amount of urine excreted are good indicators of the body’s state of hydration. Urine should be clear and in large quantities, and urination should occur frequently throughout the day. Highly concentrated urine is usually a sign of dehydration.

Body weight lost during periods of exercise is another excellent indication of the amount of fluid lost. It is important that the athlete weigh before and after activity to monitor fluid loss. For every pound of body weight lost, 2 cups (16 ounces) of fluid must be consumed for hydration. Because the body can only absorb about 1 quart of water every hour, the athlete must drink fluids before, during, and after exercise to guard against the risks of dehydration. In fact, fluid replacement must continue at least 24 hours after vigorous, sustained activity to restore lost fluids and electrolytes.

Table 2. How Much Fluid to Drink when You Are Exercising

| Time | Amount to Drink |

|---|---|

| 1 to 2 hours and 30 minutes before exercise | 2 cups (16 ounces) of cold fluid |

| 5 to 15 minutes before exercise | 1 to 2 cups (8 to 15 ounces) of cold fluid |

| Every 15 to 20 minutes during exercise | 1⁄2 to 3⁄4 cup of fluid even if not thirsty |

| Immediately following exercise | 2 cups (16 ounces) of cold water for each pound of body weight lost |

| After exercise and the next day | Liberal intake of fluids (It may take up to 36 hours to completely rehydrate.) |

What Is the Best Fluid to Drink?

For most athletes, cold water is an acceptable source of fluid replacement. Drinking cool or cold water is best because water enters the bloodstream and tissues rapidly and helps cool the interior of the body.

For most athletes, cold water is an acceptable source of fluid replacement. Drinking cool or cold water is best because water enters the bloodstream and tissues rapidly and helps cool the interior of the body.

In long-distance events (those lasting 60 minutes or more), diluted fruit juices (one part juice to one part water) or sports drinks are preferred because they supply glucose, the body’s main source of energy, as well as small amounts of sodium. Sodium has been shown to possibly increase the rate of water and carbohydrate absorption from the digestive tract and to encourage fluid retention after exercise.

Another advantage of drinking sports drinks is that the taste will actually encourage the athlete to drink. In fact, a recent study has shown that the ingestion of a sports drink by 9- to 12-year-old exercising boys resulted in a nearly two-fold increase in fluid consumption when compared to plain water.

Athletes should not drink full-strength fruit juices and other highly concentrated drinks. These create feelings of fullness and can cause cramping.

Athletes also should avoid fluids containing caffeine or alcohol. These have diuretic effects; that is, they promote the excretion of water from the body, causing the body to lose more fluid in the urine than is actually provided by the beverage. This loss of water, in turn, impairs temperature regulation and lowers the athlete’s defense against heat-related illnesses. In addition, caffeine can cause stomach upset, nervousness, sleeplessness, headaches, and irritability.

Summary

Water is the single most important nutrient needed by young athletes. If athletes exercise when they are dehydrated, they will not perform at an optimal level and will risk the onset of dangerous heat-related illness. Moreover, because the young athletes may not be as efficient at body temperature regulation as adults, the danger of dehydration and increased body temperature should be of primary concern to the performing athlete and the coaching staff.

Edited by Sheree Taylor, Regional Extension Agent, Christina Levert, Regional Extension Agent, and Helen H. Jones, Regional Extension Agent, all with Auburn University. Written by Robert E. Keith, former Extension Specialist.

Reviewed July 2022, Eat to Compete: Sports Nutrition for Young Adults—Hydration, HE-0749