Forestry

Selecting the right tree for a site is one of the most important decisions for homeowners, arborists, and city foresters. The right species in the right location enhances beauty, provides long-term environmental benefits, and reduces future maintenance costs. Thoughtful tree selection helps prevent pest and disease problems, structural failure, and premature decline. Understanding how characteristics of site and species interact is important for creating healthy, safe, and resilient landscapes.

Key Considerations When Choosing Tree Species

Climate and Plant Hardiness

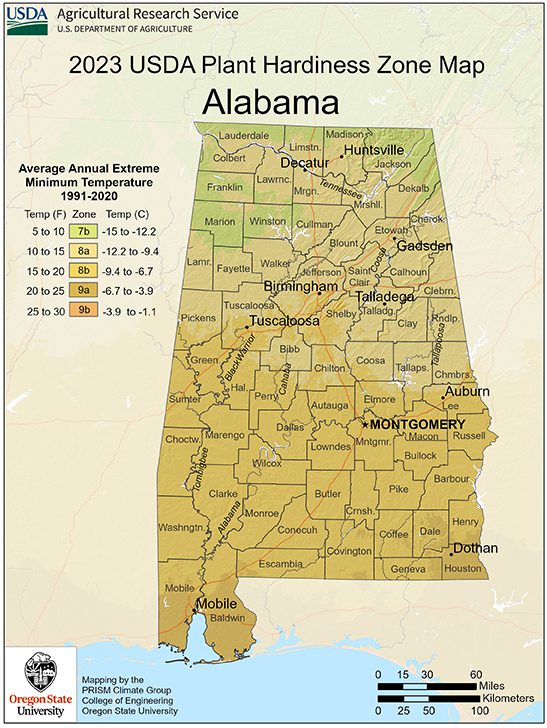

Figure 1. The 2023 USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map for Alabama is the most recent version based on data from 1991–2020.

Each tree species has limits for temperature tolerance. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Plant Hardiness Zone Map shows average annual extreme minimum winter temperatures and is an essential reference when deciding what trees will thrive in a given area (figure 1). Selecting species suited to the local climate helps ensure vigorous growth and longevity. Even small differences between zones, such as those between Zones 8a and 8b, can influence winter survival and stress tolerance in marginal species, affecting long-term health and performance. Trees planted outside their hardiness zone may experience winter injury or stress that shortens their lifespan.

Tolerance to Drought, Heat & Flooding

Species vary in their ability to handle environmental extremes. A species’ tolerance refers to its physiological capacity to survive and grow under conditions such as limited water, excessive heat, or prolonged soil saturation. Trees such as live oak (Quercus virginiana) and thornless honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos inermis) tolerate heat and drought, reducing the need for supplemental irrigation. In contrast, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) performs well in wet or flood-prone soils thanks to root adaptations that allow survival in low-oxygen conditions. Matching a species’ tolerance to site moisture and temperature is essential for long-term success.

Growth Rate & Mature Size

Fast-growing species such as hybrid poplars (Populus spp.) and willows (Salix spp.) can quickly provide shade or erosion control but often develop weaker wood because rapid wood cell expansion results in lower wood density. This structural weakness increases susceptibility to storm damage and breakage, which can shorten lifespan and increase maintenance costs. Slowergrowing trees such as oaks (Quercus spp.) or hickories (Carya spp.) require patience but may provide decades of stability and reduced maintenance. Understanding a tree’s mature size—both height and canopy spread—is crucial to avoiding conflicts with buildings, sidewalks, and power lines.

Roots, Form & Crown Shape

Root characteristics influence both tree health and infrastructure safety. Trees with aggressive or shallow roots, such as silver maple (Acer saccharinum) and willows (Salix spp.), can damage pavement or underground utilities. In contrast, species with less invasive roots, such as Japanese maple (Acer palmatum), are suitable for tight urban sites. Crown form also affects landscape function. Narrow or columnar species fit confined spaces and can serve as screens or windbreaks. Broad-canopy trees, such as red maple (Acer rubrum) and southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), offer shade and cooling benefits, while crown-porous species such as honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos) allow filtered light for understory growth.

Foliage & Flowering Traits

Deciduous trees, those that drop their leaves in the fall, provide seasonal shade and fall color while allowing sunlight in winter. Evergreens, both needle- and broad-leaf, offer year-round screening and wind protection. Flowering species, such as dogwood (Cornus florida), magnolia (Magnolia spp.), and cherry (Prunus spp.), are examples of trees that add seasonal beauty and support pollinators, contributing to local biodiversity. Balancing ornamental appeal with functional and ecological value creates a more sustainable landscape.

Resistance & Longevity

Selecting species with natural resistance to pests, diseases, and storm damage reduces future losses and maintenance costs. For example, oaks (Quercus spp.) are long lived but vulnerable to oak wilt, while ash species (Fraxinus spp.) are at risk from emerald ash borer. Resources such as university Extension publications, state forestry agencies, and peer-reviewed research provide lists of resistant cultivars and species suited to local conditions. Trees with strong wood and flexible branches, such as live oak (Quercus virginiana), are also valuable in storm-prone regions. Long-lived species provide continuous shade, carbon storage, and habitat for generations.

Benefits for Wildlife

Trees are critical habitat for birds, mammals, and insects. Choosing species that produce nuts, berries, or nectar—such as oaks (Quercus spp.), hollies (Ilex spp.), and redbud (Cercis canadensis)—enhances biodiversity and supports local ecosystems. Even in urban settings, thoughtful tree selection can create green or habitat corridors, which are connected patches of vegetation that allow wildlife to move, feed, and reproduce across developed landscapes.

Choosing the Right Site

Microclimate & Exposure

A tree’s performance depends on the specific conditions where it grows. Microclimate refers to localized climate conditions influenced by factors such as wind exposure, reflected heat, humidity, and cold-air exposure. These conditions can be evaluated by observing sun patterns, wind exposure, nearby structures, and seasonal temperature variation. For instance, a sheltered courtyard may favor magnolias (Magnolia spp.), while a windy hilltop suits hardy oaks (Quercus spp.). Evaluating microclimate helps select species that will thrive without extensive care.

Space & Infrastructure

Adequate space for both roots and canopy is essential. Trees planted too close to buildings, sidewalks, or power lines can cause damage as they mature. Selecting appropriately sized trees for confined spaces minimizes future conflicts and maintenance. In parks or open green spaces, large species can grow to their full form and provide maximum shade and ecological benefits.

Soil & Drainage

Soil texture, soil type, moisture, nutrient levels, and pH strongly influence tree health. Loamy soils support most species, while sandy soils suit drought-tolerant trees such as junipers (Juniperus spp.) and live oaks (Quercus virginiana). Heavy clay soils retain water and are better suited to species such as willow (Salix spp.) or silver maple (Acer saccharinum) that adapt to sites with moderate moisture. Where soils are poorly drained, species such as bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) thrive. Soil testing, available through county Extension offices or soil testing laboratories, can identify soil type, nutrient levels, and pH, guiding tree selection and planting practices.

Sunlight Availability

Tree species differ widely in their light requirements. Full-sun species such as ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) or honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos) require at least 6 hours of direct light per day, while shade-tolerant trees such as American holly (Ilex opaca) prefer filtered light or partial shade. Light conditions also influence flowering, foliage color, and form. Placing full-sun trees and shade-tolerant trees appropriately creates balanced, visually appealing plantings.

Purpose & Function in the Landscape

Tree selection should begin with the purpose the tree will serve. Shade trees reduce summer temperatures and lower energy costs. Evergreens provide windbreaks and privacy screens. Many native species provide ornamental traits such as flowers, fall color, and form, even though nurseries may not commonly offer them. Trees can also support ecological functions such as wildlife habitat, erosion control, or stormwater mitigation. Selecting trees that match both site conditions and functional goals ensures that they enhance the landscape for decades while reducing maintenance costs and resource inputs.

Selecting Healthy Trees at the Nursery

Healthy nursery stock is the foundation of a successful planting. Choose trees with a straight, single main trunk, evenly distributed and vigorous foliage, and no visible wounds or cracks. Inspect the trunk flare and root system to ensure stability. Avoid trees with dieback, circling roots, or pest problems. Inspecting trees before purchase prevents future structural and health issues.

Native & Non-Native Trees

Native species generally adapt better to local soils and climates and provide habitat for native wildlife. However, some urban sites have altered conditions—such as compacted soils, heat islands, or restricted rooting space—that may challenge native trees. In these situations, carefully selected non-native but noninvasive species may perform better. Check local or state guidelines before selecting a species. Non-native species can become invasive decades after they are planted in an urban landscape, so monitoring for spread in the surrounding area is essential.

Technology Tools for Tree Selection & Planning

The i-Tree software suite, developed by the USDA Forest Service, helps communities and individuals assess the benefits of urban trees. Tools such as i-Tree Species and i-Tree Planting provide guidance on selecting species suited to local conditions and estimating long-term benefits such as carbon storage, improved air quality, and reduced stormwater runoff. These free tools are available on the i-Tree website and support informed planning for both small-scale plantings and large urban forestry programs.

Conclusion

Successful tree selection relies on understanding how tree species, site conditions, and intended purposes interact. Considering factors such as climate, soil, space, and desired benefits results in healthier trees, lower maintenance costs, and greater environmental rewards. Whether for a home landscape or an urban forest, selecting the right tree for the right place ensures lasting value for people and urban forest ecosystems alike.

Georgios Arseniou, Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor, Forestry, Wildlife, and Environment, Auburn University.

Georgios Arseniou, Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor, Forestry, Wildlife, and Environment, Auburn University.

New January 2026, Selecting Landscape Trees That Thrive: Aligning Species with Growing Conditions, FOR-2195