Fish & Water

This publication explores the causes of sedimentation and the impacts it can have on Alabama’s waterways and aquatic life.

Sediment is made up of soil particles that have been detached from the land by erosion—and it is Alabama’s largest surface-water pollutant by volume. It might seem odd that something as common and harmless as soil would be considered a more impactful pollutant than chemicals such as pesticides or oil. After all, many of our rivers are sandy, but that was not always the case. Historically, most of our southern rivers were mainly gravel, cobble, or bedrock. Even now, some forested or healthy streams and rivers, such as Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa River or Upper Hillabee Creek above Lake Martin, maintain more gravel riverbeds.

Causes of Sedimentation

Figure 1. Eroded stream banks can contribute to sedimentation of waterways (Photo credit: Alex James).

Sedimentation, or the blanketing of streambeds with sediment, can occur due to a variety of factors. Any soil that is not protected or covered from rainfall by vegetation can be washed into nearby waterways and become a source of sediment pollution—among these are exposed construction sites, farm fields, dirt and gravel roads, and eroding stream banks.

Sediment pollution can also originate within a stream itself. In urban areas there are more hard, impervious surfaces, such as parking lots, roads, and roofs, that shed water into storm drains; this is then delivered into local waterways. Historically, when stream levels rose, water escaped into the floodplain, where energy was dissipated and water was absorbed into the ground. Over time, many stream channels have been physically rerouted, lined with concrete, channelized, or fragmented by culverts, effectively removing access to a floodplain.

This increased surface water runoff and the higher volumes being delivered to local streams means that stream flows can travel deeper and faster than they once did, causing erosion to the streambed and the stream bank (figure 1). This erosion can cause the stream banks to be washed away, exposing more soil to erosive forces as more vertical stream banks further channelize flows.

Sedimentation’s Impact on Waterways

Sediment can degrade water quality in a variety of ways:

Harmful turbidity. Suspended sediments in a waterway can cause the water to be cloudy, or turbid. Turbid waters can obstruct sunlight, prevent photosynthesis in aquatic plants, reduce biologically available oxygen, and increase the water temperature. Turbid waters can make it harder for fish gills to absorb oxygen and make it more difficult for visual predators to forage for food. Additionally, it costs more to treat a source of drinking water with high levels of sediment than it does to treat clearer, cleaner water.

Damaging pollutant loads. Sediment can carry other pollutants in it, such as nutrients, heavy metals, bacteria, or other pathogens originating from agricultural or industrial waste, mining, etc. Some of these pollutants may be dissolved into the water and washed downstream, while others may remain embedded in sediment on the bottom of the streambed for years.

Reduced aquatic habitat. Over time, sediment buildup on the stream bottom can reduce viable habitat for aquatic insects, fish, amphibians, and other wildlife by clogging the spaces between larger gravel, cobble, and boulders. Overall, the population of more sensitive species will be reduced, leading to a less diverse aquatic community.

Sedimentation’s Impact on Aquatic Life

The following section highlights three aquatic organisms unique to our southeastern streams that can be heavily impacted by extra sediment in the water. They are not the only ones. Nearly every organism that makes use of our water has a harder time doing so when streams are filled with sand and silt coming in from runoff.

Mussels

Figure 2. Mussels in a sandy creek bed (Photo credit: Caitlin Sweeney)

Freshwater mussels are natural filters. They feed on algae, plankton, and silts, thereby helping to purify water and keep drinking water clean. Mussels are also an important food source for many species of wildlife, including otters, raccoons, muskrats, herons, egrets, and some fish.

Alabama is home to over a hundred species of freshwater mussel, many of which are imperiled from pressures that include invasive species, water changes, and sedimentation. Our native mussels are slow and heavy, feeding mainly by filtering the water for nutrients. When streams start to fill with sand and sediment, mussels are often unable to move out of the way very quickly and can rapidly sink into the sand (figure 2). Once buried, they effectively drown in the sediment. Invasive species, like Asian clams, are light and resilient to being buried, which allows them to fill in any sandy stream the native mussels are no longer able to live in.

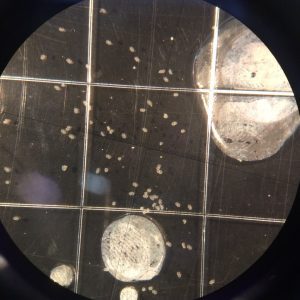

Sedimentation also impacts mussels’ mating behavior. Mussels start out in a larval form (called glochidia) that look like tiny, microscopic mussels (figure 3). These glochidia are parasitic on fish, grabbing onto the gills and using them as a free meal and ride. Mussels feed off the nutrients in the gills and drop off the fish once they have grown a little bit. This distributes them much farther in the stream than they would go if they had to move on their own. Most species of mussel have a specific species of fish they are associated with and target for glochidia distribution.

For example, the fine-lined pocketbook mussel (figure 4) uses Alabama bass and larger sunfish to spread its glochidia. To get these large predator fish near them, they release their glochidia, bound together in mucus, just outside of their shell as a lure that looks like a small prey fish (figure 5). They use their “lips” to make this wad of larvae “swim” in the current, and they will even match coloration to some small minnow species. The predator is enticed, but when it tries to eat the “fish,” the glochidia wad bursts apart, releasing the glochidia into the fish’s gills and ultimately distributing the small mussels throughout the water body. If these and other mussels are struggling to stay above sediment buildup, or are dealing with extremely turbid water, their mating behaviors can be severely limited.

- Figure 3. Glochidia under microscope (Photo credit: Brittany Barker-Jones)

- Figure 4. Finelined pocketbook mussel (Photo credit: Brittany Barker-Jones)

- Figure 5. Mussel lure display alongside log perch (Photo credit: Brittany Barker-Jones)

Bluehead Chub

Bluehead chub are actually some of our most important ecological engineers. They build piles of rocks in the middle of streams that sometimes get as large as 3 feet across and 2 feet tall. That might not sound like an essential building project for a stream, but you might be surprised.

Figure 6. Bluehead chub (Photo credit: Jason Dattilo)

Bluehead chubs are typically plain-looking fish, but during their 3-month breeding season in the spring they live up to their name. Males’ heads nearly double in size, becoming bright blue and purple and sprouting bony spikes (called tubercules) that function like a buck’s antlers (figure 6). It is not uncommon to find large males with scars along their sides from being rammed.

Bluehead chub males gather stones and pebbles from the river bottom and pile them up to form their nests and attract females. They spend their whole breeding season maintaining these rocky piles, constantly collecting, repiling, and defending the nest from challengers and predators.

When a male attracts a mate, she lays her eggs in the crevices between the piled rocks where he then fertilizes them and maintains his vigil. One nest provides far more nooks and crannies than one chub will ever need. A male will therefore share space with others so long as they are not competing for the same mate.

Drawn by the sound of rocks shuffling and clicking together, hundreds of minnows across dozens of species gather on these mounds to breed. During the 3-month breeding season, these nests swarm with some of the most colorful freshwater fish in this hemisphere. Individually, each of these fish (most of which are less than 3 inches long) would be easy prey for predators, especially with such bright colors, but schooled together on the nests they find protection in their numbers. With so many swimming together and with so many colors and patterns, they are extremely difficult for a predator to single out. This and the added protection from the male bluehead chub means that these small minnows are free to display their colors and safely reproduce.

Unfortunately, all of this relies on the chubs’ ability to find stones to build and maintain their nests. When heavy sedimentation occurs and covers the gravel beds with sand, chubs are unable to build their nests, and they move out of a stream. The crannies in the nest where the eggs are laid are at risk, too. If the stream is regularly getting sediment input, these crevices fill up faster than the chub can clean them, thus removing all of the valuable egg areas.

Without these mounds many species of minnow forgo breeding entirely or move into another stream or river less heavily impacted. Without these nests the biodiversity of our streams will decrease significantly as all the species that would have been brought in move somewhere else. Additionally, these nests and breeding displays are some of the most incredible aquatic events that happen in North America, showcasing the many colorful and unique species that live only in the Southeast.

Madtom

Figure 7. Madtom (Photo credit: Bryson Hilburn)

Growing to a maximum size of only a couple of inches, madtoms are some of our most overlooked catfish. But that does not mean they are forgettable. Madtoms are the only venomous freshwater catfish in North America. The sting might not feel like much more than a bee sting to us, but it is more than enough of a deterrence to larger fish that might otherwise try to eat them.

Ideal hiding spots for madtoms are small nooks and hollows under rocks and logs in the stream. Male madtoms pick out a suitable and protected den from which they attempt to attract mates during the breeding season.

A female madtom can lay up to 300 eggs in the den before departing, trusting the male to protect the nest and to keep the eggs aerated. The father does this by fanning his tail over the eggs.

While small dens are great protection against predators, they are also particularly susceptible to being filled in with sediment. During a rainstorm, when heavy and rapid sedimentation can occur, madtoms’ nests can be completely buried or blocked off. Even during sunny weather, an impacted stream will have a higher-than-normal level of sediment moving through it. When this occurs, sediment can rapidly collect on the nest to the point that the madtom struggles to clean it off before the extra silt suffocates the eggs.

You may rarely see madtoms in the water, yet they perform important work in cleaning up detritus and insects in streams.

Ways to Prevent Sedimentation

It is vital that we do what we can to manage and reduce the amount of sediment we allow into streams. The best way to prevent sedimentation is to keep soils covered with vegetation or managed via best management practices.

Maintaining riparian buffer areas (the 6 to 20 feet around the waterway) with native shrubs and trees can stabilize the bank with roots and slow the flow of stormwater into the stream. Best management practices can be implemented to capture and hold sediment on exposed construction or forestry sites. Green infrastructure can be established to reduce the amount of stormwater entering local waterways. These and other practices will go a long way toward protecting our waterways and aquatic life.

Daniel Gragson, Technician, Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences, and Laura Cooley, Extension Administrator, Outreach Programs, Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences, both with Auburn University

Daniel Gragson, Technician, Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences, and Laura Cooley, Extension Administrator, Outreach Programs, Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences, both with Auburn University

New August 2025, Sediment’s Impact on Waterways & Aquatic Life in Alabama, ANR-3168