Crop Production

Spider mites can cause substantial damage to crops. The key to control is an integrated pest management plan comprised of cultural, biological, and chemical tactics.

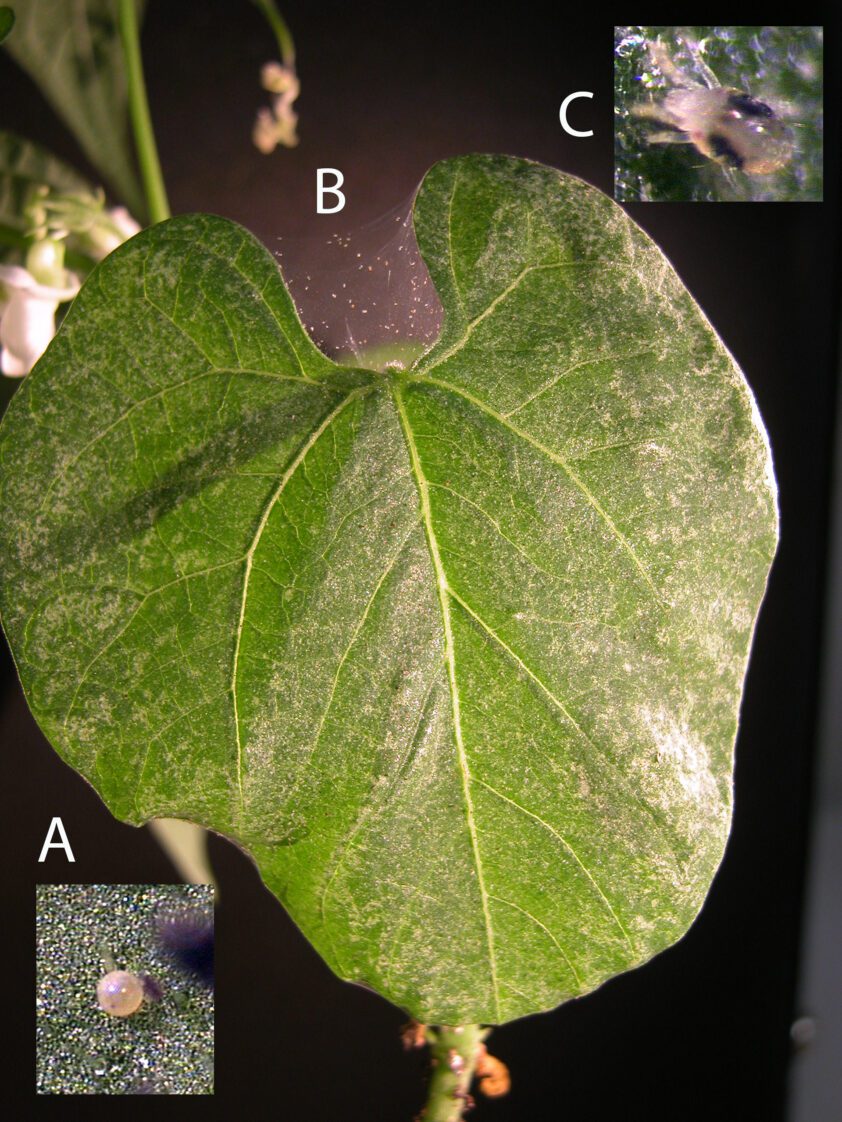

Figure 1. Spider mites in strawberry plant, Hayden, Alabama

Spider mites, while not true insects, are serious arthropod pests that can cause significant crop damage when populations build up under favorable conditions (figure 1). High tunnels and greenhouses are particularly vulnerable, as spider mites thrive in hot, dry environments. Pockets of heat and low humidity in these structures, combined with dry crop foliage, create ideal habitats. Dust accumulation, especially near sidewalls, can introduce mites that gradually spread toward the center. In open-field production, dry weather and dusty edges near roads or field margins can also trigger infestations.

Several mite species are common in the southeastern United States. Among them are the two-spotted spider mite (TSSM, Tetranychus urticae), russet mite (family Eriophyidae), rust mite, and broad mite (Polyphagotarsonemus latus). Of these, TSSM is the most widespread and damaging.

Two-Spotted Spider Mite

The genus Tetranychus includes more than 1,200 species. Of those, TSSM alone feeds on over 180 cultivated and wild plant species.

In Alabama, the most affected vegetable and fruit crops are tomatoes, cucumbers, melons, squash, beans, peppers, eggplants, strawberries, blueberries, and peaches; they also are commonly found in herbs, hops, and hemp. Infestations typically flare under hot, dry spells beginning in early summer, with earlier issues frequently occurring in tunnels and greenhouses. Adult TSSM are red to green or yellow with two black spots and four pairs of legs (figure 2C).

TSSM reproduce rapidly, completing a life cycle in 5 to 20 days at 80 degrees F. This can lead to explosive outbreaks. Webbing on leaves, flowers, and fruit is a typical sign of advanced infestation (figure 2B). These mites migrate between hosts and overwinter in crop debris or weedy field edges.

Russet Mites & Broad Mites

Figure 2. Key scouting indicators of two-spotted spider mites:

A. Translucent to pearly white eggs laid on the underside of leaves

B. Webbing across leaves and stems at advanced infestation stages

C. Adult mites showing two characteristic dark spots

(Photo credit: David Riley, UGA)

Russet mites are much smaller and teardrop-shaped, lacking the characteristic webbing seen in TSSM infestations. They may go unnoticed until symptoms such as bronzing or distorted stems appear on sensitive plant parts.

Broad mites are increasingly recognized as problematic in solanaceous vegetables (such as peppers, tomatoes, and eggplants) as well as in berries. They are nearly invisible to the naked eye and do not produce webbing. Instead, their feeding causes distinctive damage that includes curled, hardened, russetted, or bronzed leaves and twisted new growth, often mistaken for herbicide injury or viral infection; in peppers, this damage is frequently accompanied by bronzing of the leaves and fruits. Broad mites prefer warm, humid conditions and are frequently introduced through infested plant material or dispersed by wind.

Scouting Methods

Effective spider mite management begins with regular and focused scouting. These pests are extremely small, often less than 0.5 millimeters, and can be difficult to detect until significant damage has occurred.

Scouting is especially important during hot, dry periods and in high tunnels or greenhouses, where environmental conditions can accelerate population growth. In watermelon, for example, an average of four spider mites per leaf does not cause significant damage, but populations can quickly reach damaging levels if conditions are appropriate. Given this potential for rapid increase, a threshold of one to two mites per leaf is often used as the basis for deciding when to employ miticides in systems where preventive measures are not used or are insufficient.

Two-spotted spider mites are typically found on undersides of leaves, where they feed, lay eggs, and produce silken webbing. Eggs are good static indicators of TSSM presence; they are small, round, shiny, and pearly white to nearly transparent spheres (figure 2A).

Early symptoms of infestation include pale speckling or stippling, which may progress to bronzing and leaf drying. As populations increase, webbing may become visible across leaves, stems, and fruit, signaling a more advanced infestation (figure 2B). TSSM adults can survive for extended periods and feed on a wide range of plants. They are recognizable by two dark spots on their backs (figure 2C).

Russet mites and broad mites are even smaller and cannot be seen without magnification. Russet mites may cause bronzing or distortion of stems and young leaves. Broad mite damage includes curled, hardened, and distorted new growth, which is often mistaken for herbicide injury or viral infection. These mites do not produce webbing, so symptoms on the plant are often the first clue.

Use tools such as ×10 to ×20 hand lenses, white paper sheets for tap sampling, and smartphone cameras with macro lenses to improve accuracy of identification. A quick method to detect TSSM is to tap leaves over white paper or foam cups and observe for moving specks.

Begin scouting in areas near field edges, dusty zones, or near vents and doors in high tunnels, where infestations often begin. Scouting twice weekly during warm, dry conditions is recommended. Keep written records or use digital apps to track mite pressure over time. Early detection is key to avoiding outbreaks and improving management results.

Management Tactics

A successful spider mite management program relies on combining cultural, biological, and chemical control tactics as part of an integrated pest management (IPM) approach.

Cultural & Mechanical Practices

Maintaining strong, healthy plants is the first line of defense. Proper irrigation and nutrient management can help reduce plant stress, making crops less vulnerable to mite infestations. In high tunnels and open fields, weed control in and around production areas is critical, since many weeds can serve as alternative hosts. Managing weeds also helps to reduce overwintering mite populations.

Minimize the movement of equipment and people between infested and clean areas, as spider mites can hitchhike easily. Avoid mowing or cultivating near infested zones during dry, hot weather, since this can increase dispersal. In high tunnel operations, shut down production in sections during periods of high spider mite pressure to help break the cycle. After harvest, remove all crop residues promptly to reduce overwintering sites.

In open-field systems, natural rainfall can help wash off mites and suppress populations. However, in protected systems where rainfall is absent, growers may use a brief overhead sprinkler cycle to dislodge mites on the foliage, though this should be done with caution to avoid promoting diseases.

Biological Control

Predatory mites are effective natural enemies of spider mites and can be purchased from commercial suppliers. Success depends on releasing them early when pest numbers are still low. These beneficials are especially well suited for high tunnels and greenhouses, where the environment can be controlled.

Species selection should match the production system:

- Phytoseiulus persimilis performs well in humid environments.

- Mesoseiulus longipes thrives in hot, dry greenhouse conditions.

- Galendromus occidentalis is effective in outdoor crops and tolerates heat well.

- Amblyseius andersoni is a generalist predator and native to many production regions.

Some predatory mites also feed on thrips and other soft-bodied pests, making them useful in mixed-pest systems. For best results, follow supplier instructions for release rates and timing, and avoid using broad-spectrum insecticides that could harm beneficial mites.

Chemical Options

Chemical controls should be used carefully to preserve beneficial insects and reduce the risk of resistance development. Growers are encouraged to consult the most recent Southeastern U.S. Vegetable Crop Handbook available online for crop-specific recommendations on registered miticides and application guidelines.

Avoid using synthetic pyrethroids, as they often backfire in two ways. First, they can kill predatory mites and other natural enemies, which leads to secondary outbreaks. Second, they can unintentionally cause TSSM populations to flare up due to a phenomenon called hormesis, which occurs when exposure to a low dose or a particular toxic substance acts like a stimulant rather than a control. For spider mites, exposure to pyrethroids can increase reproduction rates, making the problem worse. Miticides from the following Insecticide Resistance Action Committee groups have shown good efficacy and selectivity:

- Group 10B: etoxazole (Zeal)

- Group 20B: acequinocyl (Kanemite)

- Group 20D: bifenazate (Acramite)

- Group 21A: fenpyroximate (Portal)

- Group 25A: cyflumetofen (Nealta)

Always rotate products with different modes of action and follow label instructions for rate, timing, and reentry intervals. Coverage is essential for success, especially with contact miticides.

Organic Options

For organic systems, effective options include oils and biopesticides with contact activity:

- Mineral oil (TriTek), paraffinic oil (SuffOil-X), and neem oil suppress low populations if applied early.

- Chenopodium extract (Requiem)

- Isaria fumosorosea (PFR-97)

- Chromobacterium subtsugae (Grandevo)

- Potassium silicate (Sil-Matrix)

- Botanical oil blends

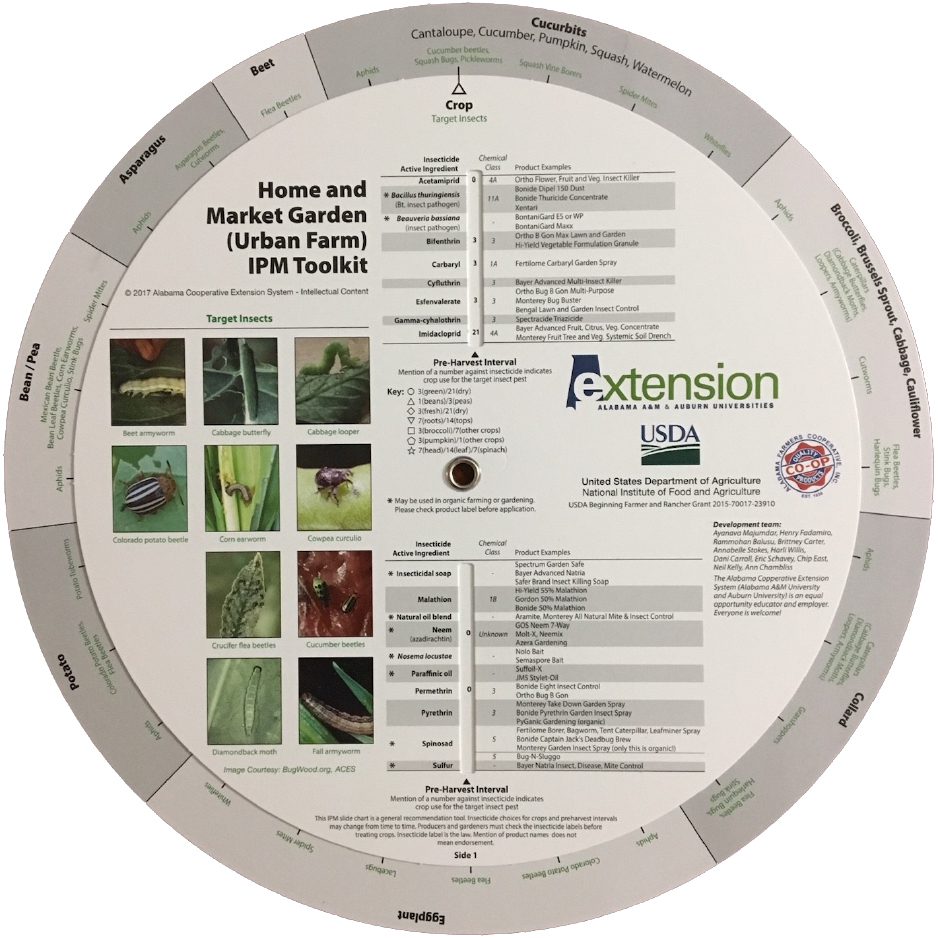

Home and Market Garden Urban Farm IPM Toolkit

More Information

- Twospotted Spider Mites on Landscape Plants. S. D. Frank (2009). North Carolina Extension Service Bulletin ENT/ort-25.

- Twospotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae. Fasulo, T. R., and H. A. Denmark (2000). Koch (Arachnida: Acari: Tetranychidae) UF/IFAS EENY-150.

- Two-Spotted Spider Mite Management. A. Majumdar (2024). ACES Blog.

Predatory Mite Sources

- Arbico Organics: Mite Predators

- Rincon-Vitova Insectaries: Control of Pest Mites

Home & Urban Garden IPM Slide Chart

The Home and Market Garden (Urban Farm) IPM Toolkit is available for urban farmers and community gardeners. This interactive wheel slide chart has both conventional and organic insecticide listings for nearly 20 different crops. This publication also has listings of common insect pests with images that may help when scouting garden vegetables. Email cremonez@auburn.edu to get a copy or to attend a vegetable IPM training event near you.

Paulo Gimenez Cremonez, Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology, Auburn University

Paulo Gimenez Cremonez, Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology, Auburn University

New January 2026, Spider Mite Scouting & Management in Vegetable Crops, ANR-3210