Coastal Programs

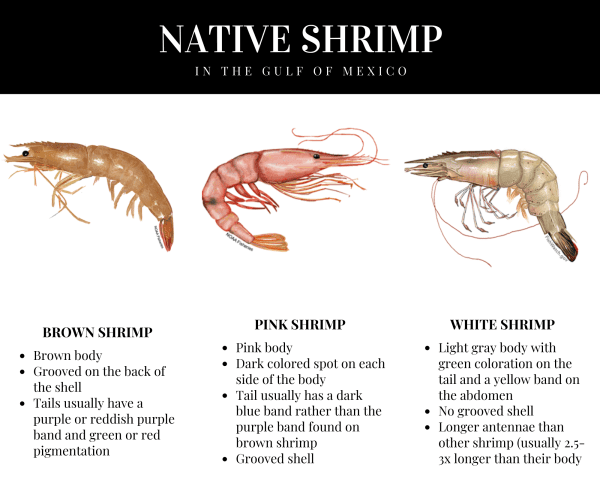

Figure 1. Native shrimp found in Alabama (Photo credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

The commercial shrimp industry is one of the most valuable fishing industries on the Gulf Coast. Whether shrimp are wild caught or farm raised, success requires an understanding of shrimp biology, habitat requirements, and management approaches.

Shrimp are among approximately 8,500 species of invertebrates called decapods (10 feet) in the class Crustacea. The Alabama shrimp industry consists of wild-caught and farm-raised species, with wild caught having a far bigger harvest. The waters of Alabama contain fifteen to twenty-two species of shrimp, but only three are eaten and found in commercial quantities in the Gulf of Mexico (figure 1): brown (Farfantepenaeus aztecus), white (Litopenaeus setiferus), and pink (Farfantepenaeus duorarum).

In 2021, commercial shrimp landings in Alabama totaled 10.4 million pounds ($34.3 million) of white shrimp, 10.8 million pounds ($27.7 million) of brown shrimp, and 2.9 million ($7.6 million) of pink shrimp, making this a valuable industry to the coastal economy (www.fisheries.noaa.gov).

For those in Alabama’s shrimp industry, many factors go into a successful harvest. Chief among them is cultivating and preserving the habitats needed by shrimp to thrive.

Alabama Wild Shrimp

Identification

The three wild shrimp species are very similar in appearance but can be distinguished by certain features. Brown and pink shrimp have grooves on either side of the spine on the back of the head. They also have similar grooves on the last body segment before the tail segment. Pink shrimp have a dark (sometimes pinkish red) blotch on each side of the body about halfway between the back edge of the head and tail. White shrimp have no grooves and are easily distinguished from brown and pink shrimp.

Biology

Figure 2. Shrimp postlarvae

Brown, white, and pink shrimp spawn in the offshore waters of the Gulf of Mexico. The eggs hatch and the microscopic shrimp pass through several larval developmental stages before turning into what we recognize as shrimp. During this time, the tiny postlarvae shrimp (figure 2) are carried by tides and currents into the shallow, marshy areas of Mobile Bay and Mississippi Sound.

In protected, productive marshes, postlarvae feed on a rich variety of food items and grow rapidly into juvenile shrimp. As postlarval shrimp develop into juveniles (about 1 to 2 inches in length), they begin to leave the protected areas of the marsh for the bays and sounds. Here, the juveniles grow to adult and harvestable size. Adult shrimp then continue to move to the deeper waters of the Gulf to spawn and complete their life cycle. The period from egg to spawning adult is about 1 year. Most shrimp do not survive to spawn again.

While all three species have this basic life cycle, each differs in the time of spawning and time of migration. Brown shrimp spawn offshore from November to April. Young adults move out of protected marsh areas from May to July and are harvested in large numbers during this period.

White shrimp spawn offshore from March to October. Juvenile whites tolerate freshwater better than brown shrimp do and may be found in very low-salinity water. Young adults migrate to offshore waters from July to November and are caught primarily during these months.

Pink shrimp spawn offshore from May through November and migrate out of marshes from April to September. Pink shrimp are caught most often in the early spring.

The different life cycles explain why each species is most abundant during certain times of the year. Understanding these life cycles is a basis for shrimp management plans undertaken by the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) Marine Resources Division.

Management

The Alabama DCNR manages shrimp primarily by protecting young shrimp in two ways:

- The most-productive nursery grounds, such as Weeks Bay, are permanently closed to all shrimping activities. This allows juveniles to grow to harvestable size and reduces damage to the fragile marsh from fishing activities.

- Various areas of state waters may be closed for short periods when DCNR personnel observe that migratory shrimp are below harvestable size. When sampling in these areas indicates that shrimp have grown large enough, the areas are reopened for shrimping.

These measures are taken to ensure that shrimp are of legal size and that enough adults escape to spawn offshore and provide the following year’s harvest.

Shrimp Abundance and Environmental Factors

A single female shrimp produces 500,000 to 1 million eggs. Only a tiny percentage of these hatch and survive the inshore migration to the marshes. Even fewer survive the numerous predators in the marsh, which prey on young shrimp for food.

Despite the incredible yearly losses, enough shrimp survive to spawn and continue the cycle. In fact, shrimp can produce so many young that the shrimp harvest does not appear to depend upon the number of shrimp present the previous year. Instead, environmental factors, especially large amounts of freshwater from spring flooding and cooler-than-normal water temperatures, seem to control the number of adult brown shrimp available each year. Long periods of high river flow reduce the salinity of the nursery areas. Combined with a late-arriving spring, this may result in poor conditions for the survival and growth of juvenile brown shrimp.

Shrimp abundance fluctuates from year to year depending on the weather. However, long-term health of the shrimp population relies on the preservation of coastal Alabama marshes, which provide food and protection for the postlarval shrimp.

Alabama Farmed Shrimp

Pacific white shrimp can be farmed in Alabama in areas with access to low-salinity aquifers that are too salty for human consumption or traditional agricultural practices (figure 3). Shrimp farmers in Alabama purchase postlarval shrimp from commercial hatcheries (usually in Florida or Texas), transport them in live hauling tanks, or have them shipped to their farms in full-strength seawater (approximately 30 parts per thousand). Because they are acclimated to this high-salinity water, they must be acclimated slowly to low-salinity water upon arrival on the farm.

Counties with inland shrimp farms have included Lowndes, Greene, Sumter, and Tuscaloosa. These inland low-salinity water sources can have chloride levels above 700 mg/L.

Salinities of wells used for shrimp production have ranged from 2 to 11 parts per thousand (ppt). Ocean water typically has a salinity of 34.5 ppt. Inland shrimp farmers use these wells to fill earthen ponds to grow the shrimp (figure 4).

- Figure 3. Market-size farm-raised Pacific white shrimp harvested in Greene County, Alabama

- Figure 4. Aerial view of shrimp ponds in west Alabama (Photo credit: Troy Bader, USDA)

- Figure 5. Shrimp harvest in Alabama

Pacific white shrimp (L. vannamei), which are not native to the Gulf of Mexico, are the farmed shrimp species of choice by most shrimp producers. This species is desirable due to its tolerance for low-salinity water, desirable feed conversion ratio, and ability to be cultured at high densities with low aggression.

While the salinity and chloride levels in these inland areas are acceptable for shrimp farming, farmers must add large amounts of fertilizers each year to increase the potassium and magnesium concentration in pond water to optimize conditions for shrimp production. Potassium and magnesium fertilizers are added to ponds several weeks before stocking. Over time, potassium and magnesium can be tied up by pond bottom soils. More than one annual application of these fertilizers is often required for each production pond used to raise shrimp.

Alabama shrimp farmers produce approximately 200,000 to 300,000 pounds of shrimp annually (figure 5). This ranks behind Texas and Florida, and the production and value is small compared to the number of shrimp caught in the Gulf. In 2020, commercial fishing operations landed approximately 25.3 million pounds of wild shrimp in Alabama.

Farmed Shrimp Growing Season

Figure 6. Farmed Pacific white shrimp raised at Claude Peteet Mariculture Center in Gulf Shores, Alabama

The growing season for commercially raised shrimp in Alabama is May to October. Shrimp must be stocked in late spring to allow water temperatures to be high enough to support growth. They must then be harvested in the fall before water temperatures drop to levels that will not support optimal shrimp growth and survival.

Throughout the production cycle, shrimp are offered a plant-based, high-protein feed (32 to 35 percent protein) daily. Shrimp are sampled weekly to track growth and actively manage production ponds for optimal water quality. At harvest, ponds are drained. Shrimp are removed and stored on ice to sell to the public or transported to a seafood processing plant on the coast.

In 2018, Alabama had four active shrimp producers, growing around 300,000 pounds of Pacific white shrimp annually. One problem Alabama shrimp farmers consistently face is low survival rates. Though the shrimp that survive tend to grow very well, shrimp loss can compromise a farm’s economic feasibility.

Marketing Shrimp

There are a few ways that Alabama shrimp farmers market their shrimp after harvest. Some producers sell directly to the public at harvest with no processing. Others send harvested shrimp to processors and later sell the processed and packaged shrimp to restaurants, grocery stores, or the public.

Consumers value locally grown food, but it can be hard for Alabama producers to compete with the prices of imported Asian shrimp. For example, the average cost for Alabama farmers to produce a pound of shrimp in 2015 was $2.30; Asian shrimp could be purchased at that time for $2.25 to $2.45 per pound. The cost of production in 2022 for inland shrimp farmers using earthen ponds in the Southeast, including Alabama, has been reported by commercial producers to be around $2.50 a pound, although it has approached $3.00 a pound.

Alexis Weldon, Administrator, Outreach Programs; D. Allen Davis, Professor; and Luke A. Roy, Associate Extension Professor, all with Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences, Auburn University

Alexis Weldon, Administrator, Outreach Programs; D. Allen Davis, Professor; and Luke A. Roy, Associate Extension Professor, all with Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences, Auburn University

Revised November 2022, Shrimp in Alabama, ANR-1028