Landscaping

The camellia has long been a pampered and cherished plant, considered more delicate and difficult to grow than it really is. Gardeners today are rediscovering the camellia as an evergreen shrub of ruggedness and great beauty. Learn about the ideal growing environment, planting and care tips, and problem solving for common pests. Also included are illustrated instructions for propagation along with some varieties appropriate for the beginning grower.

Origin and History

From the ancient temple gardens of China and Japan, through the ornate conservatories of eighteenth-century Europe, to the stately plantations of America’s nineteenth-century South, the camellia has been a pampered and cherished plant, a living symbol of elegance and aristocracy. Legends of mythology and romance, fancy and fiction have made the camellia seem more rare and expensive, more delicate and difficult to grow than it really is.

From the ancient temple gardens of China and Japan, through the ornate conservatories of eighteenth-century Europe, to the stately plantations of America’s nineteenth-century South, the camellia has been a pampered and cherished plant, a living symbol of elegance and aristocracy. Legends of mythology and romance, fancy and fiction have made the camellia seem more rare and expensive, more delicate and difficult to grow than it really is.

Gardeners today are rediscovering the camellia as an easy to grow evergreen flowering shrub with many uses, incredible ruggedness, and great beauty. A wider variety of flower forms, new hybrids, seedlings, and hardy species, as well as improved cultural techniques and devices, have pushed the outdoor growing areas of the American camellia belt farther north each year. Even in the coldest regions, the camellia has become a fixture in the home greenhouse.

The name camellia was given to the genus by the Swedish botanist Linnaeus, who developed the binomial system of nomenclature used to classify plants. The pronunciation of camellia as either ca-mee-lia or ca-mell-ia is acceptable. The natural home of the camellia is an area encompassing Southeast Asia, China, Japan, and various islands and countries from Viet Nam to Burma. More than 200 species of camellias have been identified with most of these being distributed throughout southern China. The most economically important species of the genus is Camellia sinensis, the common tea plant. Camellia japonica is the most widely grown ornamental species of the genus. More than 20,000 varieties or cultivars of various species and hybrids generally grown by amateur camellia hobbyists in the English-speaking world have been described. Flower colors, shapes, and bloom sizes show remarkable diversity. Seedlings of crosses with Camellia reticulata and other species have produced extensive variations in flower and leaf sizes and growth habits. Camellia sasanqua is another widely grown species.

Classification of Cultivars or Varieties

Camellias vary in color, size, and form depending on the season, location, soil, nutrition of the plant, and the aerial environment. The division and classification of the flower forms, colors, and sizes of camellias have been established by the American Camellia Society in the official nomenclature book as follows:

- Class I, SINGLE, One row of not over eight regular, irregular, or loose petals and conspicuous stamens (Yuletide)

- Class II, SEMI-DOUBLE, Two or more rows of regular, irregular, or loose petals and conspicuous stamens (Frank Houser)

- Class III, ANEMONE, One or more rows of large outer petals lying flat or undulating; the center a convex mass of intermingled petaloids and stamens (Elegans)

- Class IV, PEONY, A deep rounded flower of either a Loose Peony Form consisting of loose petals, which may be irregular, and intermingled stamens, and sometimes intermingled petals, petaloids, and stamens in the center (Vedrine) or a Full Peony Form consisting of a convex mass of mixed irregular petals, petaloids, and stamens or irregular petals and petaloids never showing stamens (Debutante)

- Class V, ROSE FORM DOUBLE, Imbricated (layered like scales) petals, showing stamens in a concave center when fully opened (Mathotiana)

- Class VI, FORMAL DOUBLE, Fully imbricated, many rows of petals, never showing stamens (Grace Albritton)

Blooming periods for the southeastern United States are identified as follows:

- E. (Early), September to early November

- E.-M. (Early to Midseason), Early November to Mid December

- M. (Midseason), Mid December to Mid February

- L. (Late), Mid February to Mid March, varying with the year

Some camellia varieties sport (mutate) freely, producing new color forms. This provides even more variability to the species and genus.

Varieties (Cultivars)

With more cold hardy varieties becoming available, camellias are now being grown all over Alabama. In addition to the southern United States, camellias are popular in Australia, China, England, France, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Southeast Asia, and southern Europe, as well as Washington, D.C., California, and Oregon.

The camellia selections in Table 1 are especially suitable for beginning camellia enthusiasts in Alabama. Nursery workers may not have them all. Be sure you consult a local camellia grower or county Extension agent before paying for a variety unknown to you or a variety that is not listed in one of the three tables in this publication. Start with some of these 12 varieties, join a local camellia club and the American Camellia Society, and attend a camellia show to decide your next plants for purchase or grafting.

Table 1. Varieties for the Beginning Camellia Grower

| Variety | Description |

|---|---|

| Sparkling Burgundy | A C. sasanqua that blooms profusely early, peony, ruby rose + lavender |

| Donation | Hybrid of C. saluensis x C. japonica, semi-double, pink, heavy bloomer. These two camellias are great for hedges or for a great splash of color, but not for the vase. |

| Adolphe Audusson (& Sports) | Blooms midseason, semi-double, red, average growth rate |

| Betty Sheffield (& Sports) | Midseason, semi-double, white and pink combinations, average growth rate |

| Debutante | Blooms before Christmas, peony form, midseason, light pink |

| Dixie Knight (& Sports) | Mid- to late-season, loose peony, irregular petals, red |

| Elizabeth Boardman | Midseason, semi-double with fluted petals, white with medium growth rate |

| Fran Mathis | Early to midseason, semi-double, champagne pink |

| Grand Slam | Midseason, semi-double to anemone form, brilliant dark red |

| R.L. Wheeler | Early to midseason, semi-double to anemone, very large, pink |

| Royal Velvet | Midseason, semi-double, dark velvet red |

| Ville de Nantes | Mid- to late-season, semi-double, red and white, slow growth rate |

Table 2. Established Varieties That Do Well in Central Alabama

| Color | Variety |

|---|---|

| Early to Midseason Bloomers | |

| White | Alba Plena, Charlie Bettes, Conrad Hilton, Dear Jenny, Emmett Barnes, King Cotton, Nuccio’s Gem, Silver Anniversary, White Empress |

| Pink | Berenice Boddy, Dr. Tinsley, Elizabeth Le Bey, High Hat, Kick Off, Lady Clare, Marie Bracey, Pink Perfection, Simeon |

| Red | Daikagura Red, Laura Walker, Reg Ragland, Terry Gilley, Tomorrow, Vulcan |

| Variegated | Carter’s Sunburst & Sports, La Peppermint, Magic City, Margaret Davis, Mona Jury, Ward’s Daikagura |

| Mid- to Late-Season Bloomers | |

| White | Leucantha, Man Size, Onetia Holland, Sea Foam, Snowman, White-By-The-Gate |

| Pink | C.M. Wilson, Diddy Mealing & Sports, Emily Wilson, Fashionata, Jessie Katz, Magnoliaeflora, Marguerite Sears, Miss America, Moonlight Sonata, Omega, Pink Champagne, Rev. John Drayton, Show Time, Spring Sonnet, Tiffany, Tomorrow & Sports |

| Red | Aunt Jetty (Governor Mouton), Firebrand, Flame, Kramer’s Supreme, Mrs. Charles Cobb, Professor Charles E. Sargent |

| Variegated | Charlotte Bradford, Donckelarii, Gigantea, Herme, Iwane, Lady Kay, Lady Van Sittart, Lindsay Neill, McVey’ Guilio Nuccio, Miss Charleston, Ville de Nantes |

Table 3. Varieties from C. Reticulata x C. Japonica Crosses

| Dr. Clifford Parks: Midseason, red with orange cast, semi-double to anemone to loose to full peony form |

| Frank Houser: Early to midseason, red, semi-double to peony form |

| Terrell Weaver: Midseason, flame to dark red, semi-double to loose peony form, unusual variegation |

| Valentine Day: Midseason, salmon pink, formal double with rosebud center |

The Environment for Growing Camellias

Location

Some camellias can be grown in full sun, although most grow and produce better flowers in partial shade where the blooms and foliage are protected from sunburn. However, camellias in dense shade often become spindly and produce fewer blooms. A site under pine trees is ideal because pines provide filtered light year-round for growth, winter protection, and natural mulch from the pine needles. Do not plant camellias where hardwood shade trees with shallow root systems will compete with the camellias for nutrients and water. Avoid windy, exposed sites since wind can be detrimental for camellias in winter and summer.

Cold Hardiness

Varieties and the different flower forms vary in their resistance to cold. Generally, cold spells with temperatures below 20 degrees F reduce the size of the blooms. It usually takes less cold to affect the blooms and bloom buds than it takes to affect the plant itself. Open blooms can be damaged by temperatures of 26 degrees F, but may be untouched at 28 degrees F, if partially shaded or recently wet by rain. Some varieties, double flowers in particular, often fail to produce typical or perfect blooms after the temperature has dropped below 20 degrees F. However, damage can occur between 20 degrees F and 30 degrees F if the drop occurs quickly after a period of warm weather.

Camellias in a northern or western exposure, unless otherwise protected from intense winter morning sun, will usually stand more cold weather than those in an eastern or southern exposure. Therefore, only early and late flowering, single, semi-double, and peony form camellia varieties should be planted outside in the northern half of Alabama. In the southern half of the state, camellias can be grown without too much concern; however, many camellia enthusiasts grow their prize camellias under protection in plastic or glass greenhouses.

Soil

Camellias will grow in sandy, loamy, or clay soils that vary greatly in their water-holding capacity and in the presence of the essential elements of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK). All soils contain these elements and may also contain the trace elements of iron, magnesium, copper, calcium, and others. Good garden loam containing organic matter (leaf mold, compost, or humus) would be expected to contain these essential elements as well as the trace elements to some degree. Camellias do well in soils with an acid reaction (pH 5.0 to 6.5) and do poorly in alkaline conditions (pH above 7.0). Contact your county Extension agent for information about the soil analyses offered by the Auburn University Soil Testing Lab.

The texture of the soil determines its capacity for water retention and its ability to hold nutrients. Clay soils hold moisture longer than sandy and loamy soils, but they are less permeable. They tend to shed water unless a mulch of coarser materials (pine needles or pine bark) allows the water to filter through gently. The natural soil for camellias contains humus or well-decomposed organic matter, is acid in reaction, and is highly retentive of moisture but drains well. In camellia culture, the value of organic matter cannot be overemphasized, since it improves aeration and drainage and adds moderately to soil acidity.

Water

Adequate water is necessary for quality and quantity of blooms as well as for proper development of new stems and foliage after the blooming period. The supplemental watering routine of the individual grower depends on the species of camellia, the size and age of the plant, soil type, air temperature, humidity, and rainfall throughout the year in his or her locality.

Soil Aeration

The top growth of all plants is directly related to the extent and vigor of the root system. Physical characteristics of the soil, such as air and water-holding capacity, determine, to a large extent, the growth and useful activity of plant roots. An ideal soil is actually composed of 50 percent soil particles and 50 percent pore space half filled with water.

A healthy root system results in vigorous foliage growth in camellias. Excessive soil water fills the air spaces and reduces the oxygen for respiration by the roots. Too much soil water causes the accumulation of carbon dioxide and other gases, which can be toxic to the roots and can provide a favorable environment for root-rotting fungi. Thus, excessive soil water kills plant roots, leaving the plant unable to absorb adequate water. This results in drought symptoms in the leaves, including wilting and browning of the margins or tips of the leaves. Nutrient uptake is reduced. Iron deficiency symptoms (yellowing between the veins of younger leaves) are often the first indications of root injury.

Although poor aeration and drainage are common causes of root problems, drought, excessive fertilization, plants set too deep, and other undesirable cultural practices can reduce root efficiency and result in poor plant growth. High populations of root-infecting nematodes also can reduce plant vigor by feeding on the roots and reducing the area of the root that actively supplies the plant with water and nutrients.

Drainage

Camellias are native to high rainfall areas and to sites providing good natural drainage. Camellias require both soil aeration and water. After establishment, camellias will survive drought longer than they will tolerate poorly drained soils. Camellias with long-established root systems require infrequent watering except under extreme drought stress.

Planting and Caring for Camellias

Planting

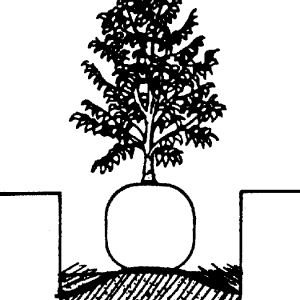

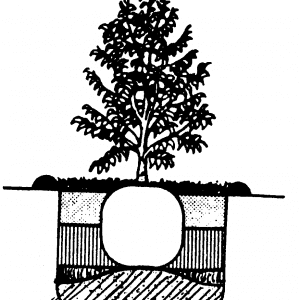

The best time to plant camellias is early fall or winter, when temperatures are above freezing. Container-grown plants can be transplanted or repotted at any time of the year. Planting and transplanting both require meticulous care, depending on the size and age of the plant. If possible, prepare the site and soil several weeks before planting. Most camellia enthusiasts recommend digging a hole in sandy and loamy soils twice the diameter and as deep as 1 1⁄2 times the height of the plant’s root ball. In tight (clay) soil, the planting hole should be even larger. Build a mound of one part soil and one part fine pine bark mixed in the bottom center of the hole (Figure 1). Place the plant on the mound and fill with your planting mix halfway to the top of the root ball (Figure 2).

- Figure 1. Place plant on mound built in the bottom of the planting hole. The top of the root ball should be 1 inch above the surrounding ground.

- Figure 2. Backfill the hole with soil to a level about halfway to the top of the root ball. Water thoroughly, fill the remainder of the hole, water again, and add mulch.

Soak thoroughly and finish filling the hole with soil mix, water again, and mulch the watered surface of the soil with 2 to 4 inches of pine straw, pine bark, or leaves. Mulch holds moisture, reduces surface evaporation, keeps the soil cooler, suppresses weeds, and eliminates the need for cultivation. The root ball of the plant should be at least 1 inch above the surrounding ground level since the camellia will settle with subsequent watering and rainfall. Container-grown plants are sometimes root-bound. The root ball should be broken by cutting it open with a knife in three or four places so the new roots will grow into the planting mix. Do not overwater in any soil type. Spacing of plants depends on the natural habit and form of the camellia variety—6 to 8 feet apart should be adequate for most varieties.

Mulching

Immediately after planting and watering, camellias should be mulched 2 to 4 inches deep with pine needles, pine bark, or leaves. Peat moss and sawdust (unless old and well rotted) are generally not good for use as mulch since they can form a crust when they dry, making it difficult to get water and air to the roots.

Fertilizing

Camellias are not generally fertilized the first year after planting, especially if the soil is high in organic matter. After the first year, apply fertilizer in the spring after blooming but before new growth starts. With many fertilizers, small amounts at frequent intervals are better than heavy applications. Special camellia fertilizers as well as 8-8-8, 10-6-4, cottonseed meal, or cow manure are available at your local seed store. Some fertilizers have up to 70 percent of the nitrogen in a slow-release form, which is less likely to burn the roots. One application in early spring after blooming should be followed by a second application in mid-June to early July. A soil test is the best way to determine the nutrient status of the soil. Scatter the fertilizer evenly on top of the mulch and away from the main stem of the plant. Water the fertilizer into the soil. Do not fertilize after July so the plants will have a longer time to harden off and avoid freeze damage.

Pruning

Camellias require only light pruning, if any, to remove dead wood, to shape into compact plants, and to thin inside limbs to increase air movement. The best time to prune is after blooming and before new flower and vegetative buds form.

Disbudding

Disbudding is usually done to increase the size and quality of the blooms. This is attained by removing excess flower buds to one per terminal. Disbudding varies depending on the age, size, and variety of camellia. It is usually done in late August and September.

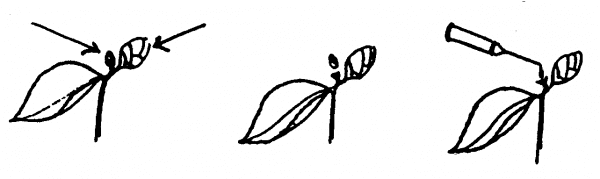

Gibbing

Gibbing is the application of the plant hormone gibberellic acid (GA) to a spot near the bloom bud to induce earlier than normal blooming for the variety. It also increases the size, texture, and keeping the quality of the bloom, but it often changes the color. GA is available from many sources, including the American Camellia Society. The recommended mixture is 1 gram of GA to 2 ounces of distilled water, which should be refrigerated when not in use.

Gibbing is done in late summer (after Labor Day) by breaking or twisting out the vegetative bud at the base of a flower bud. Use a small eye dropper to place 1 drop of GA in the small receptacle of the growth bud (Figure 3). Most, but not all, varieties respond favorably to gibbing. Do not gib young plants. Even on mature plants, gib only a few buds each week—never all the buds. Results can be noted in 4 to 8 weeks, depending on the variety, location, and environment.

Figure 3. Remove the vegetative bud and apply 1 drop gibberellic acid (GA) solution.

Propagation

Camellias can be propagated from seed (sexually), by rooted cuttings, by cleft grafting, and by air layering (asexually).

Sexual Propagation

Propagation By Seed

This is the easiest method for producing a large number of camellia plants. If naturally occurring seed are personally collected, acquire them from vigorous-growing varieties that are known seed producers. Then, if they grow into vigorous plants but have poor blooms, they can still be used for grafting understock. Plants from seed will vary in flower color and form and are usually unlike either parent. Chance seedlings, however, are the way most new varieties have originated in the past. Today, deliberate varietal and hybridizing crosses are originating many new varieties. If you make varietal crosses, be sure to keep accurate records and make reciprocal crosses of varieties with characteristics that you desire. If your crosses result in seed, great! Plant the seed—a new variety may have been developed.

Water, heat, and light are the three most important factors for rapid seed germination. Excess water is the most likely factor to cause seed rotting. If the drainage of the medium is good and relatively sterile, chances of rot are slim. Seed can be germinated in a greenhouse or home or stored until spring. Seeds of camellias ripen in the fall, usually in September and October. They germinate quicker if planted immediately after harvest. A germinating medium composed of peat moss or 2⁄3 sphagnum moss and 1⁄3 Perlite is recommended. If not planted at once, the seed coat of camellias hardens in storage.

Some growers crack hardened seeds with pliers or nick them with a file to allow moisture to enter more readily to swell and germinate the seed. The peat moss or sphagnum moss should be moistened and then squeezed dry before mixing with the Perlite. Perlite is sterile, and the pH of peat moss is low enough to prevent bacterial growth. Perlite permits water to filter through freely, still holding adequate moisture. Plant seeds with eye down, which is where the root will break out, and cover with a ¼-inch layer of peat moss or Perlite.

Planting can be in a flat of individual containers (peat pots), while seed of known origin can be planted in flats in rows. Individually numbered stakes are used to identify each seed source. After planting seed, thoroughly water with a fine spray or mist. The time between waterings will depend on heat, light, and location of the flat or container. Many hobbyists put camellia seed in large-mouthed jars or plastic bags in thoroughly moistened peat moss and then keep them on top of a water heater or other warm place. Germinated seeds are removed when the taproot reaches 2 inches in length. The tip is pinched off before planting in 4-inch or larger pots. The normal growing span before camellia seedlings bloom is 3 to 5 years. During this time, the plants will require pruning and good cultural treatment to develop good quality plants.

Asexual Propagation

Asexual propagation provides a way to reproduce camellias that is certain to yield the variety desired. Asexual propagation methods include rooting cuttings, cleft and surrogate grafting, and air layering.

Propagation By Cuttings

Camellia cuttings can be rooted in almost any season, although the optimal time is July, after the new spring growth has hardened. A greenhouse, cold frame, or a deep-rooting box is needed. Cuttings are taken from 3 to 5 inches of terminal hardened growth. The bottom leaves are removed from the cutting, leaving two to three leaves and the vegetative buds on the tip of the cutting. Flower buds are removed, if present. Slice off the lower end with a sharp knife or razor at an acute angle. Dip the cut stem end into Rootone, Hormodin, or a similar root-stimulating compound to stimulate rooting before sticking into a nail hole in the lightly moistened medium to half the cutting’s length. Firm the medium, and water the cutting.

The preferred rooting medium is 1 part Perlite or peat moss mixed with 1 part sand. When rooting only a few cuttings, a 1-gallon plastic container of the medium is adequate. After sticking up to 6 cuttings, place a 2- or 3-liter soft drink bottle with the bottom cut out over the cuttings. Then place the container and bottle in the shade. When rooting a large number of cuttings, use a large deep box or bin with openings for drainage in the bottom. Place 1 or 2 inches of a good soil in the bottom to cover a layer of gravel before adding 4 to 6 inches of the rooting medium. Cover with clear plastic, such as dry-cleaning bags. The box must be deep enough to allow for 6 to 8 inches of cutting growth. Be sure the box is shaded. Both procedures require checking for moisture levels and high humidity, which are important for root development of the cuttings.

After 2 to 3 months, camellia cuttings should have developed a fibrous root system varying with the variety and the growing environment. Rooted cuttings can be potted to large peat pots or directly into 1-gallon containers in a soil high in organic matter. Do not plant too deeply, whatever the size of container used. It is the health and vigor of the rooted cutting and not the size of the container that is important. The soil medium in the container should have a pH of 5.5 to 6.5. It is important that the medium drains well, holds nutrients, holds moisture, is kept in the shade, and is topdressed with low levels of fertilizer, such as 18-6-8 or liquid 20-20-20.

Propagation By Cleft Grafting

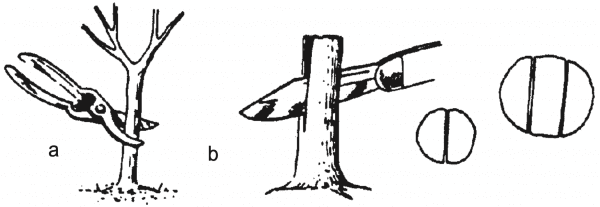

The cleft graft is a widely used method of propagating camellias. Any vigorous camellia can be used for rootstock, although C. sasanqua is widely used because of its vigor, disease resistance, and ability to withstand varying soil conditions. On the other hand, vigorous growing C. japonica and seedlings with poor blooms may be superior, being more cold resistant and more compatible. Grafting outdoors is usually done in mid to late February and early March. It can be done in a greenhouse in December.

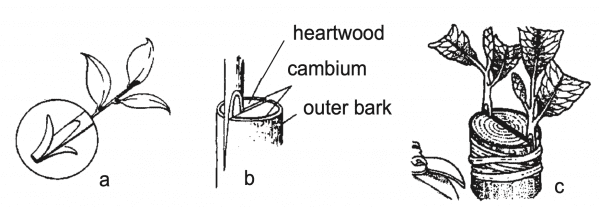

Figure 4. Prepare the understock for grafting: (a) choose healthy understock; cut straight across about 3 inches above ground; (b) cut down through the center about 11⁄2 inches. (Large understock may be split twice.)

The understock may vary in diameter from ¾ to 1½ inches and should be cut or sawed off smoothly about 2 to 3 inches above the ground or first lateral root (Figure 4a). Use a knife to split the stem of the understock (Figure 4b). Select the scion from healthy plants and from the mature growth of the past season. Scions should be terminal tips 3 to 5 inches long (Figure 5a). Use a sharp knife or razor to fashion a long, bilateral wedge at the base of the scion. The slit in the understock can be opened and managed with an ice pick or screwdriver, while placing the scion wedges in place. It is critical that the cambium layer of the stock and the scion line up (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. Procedure for cleft grafting: (a) select strong tip cutting, leaving enough stem to trim to a 11⁄2-inch wedge; (b) pry open split in understock and insert scion wedge (be sure to align green inner bark); (c) insert two scions, one on each side of the understock.

The cambium layer is the thin green line within the bark area. It is exposed on both sides of the scion wedge. On a ¾-inch or larger understock, insert two scions, one on each side of the understock (Figure 5c). After the scion or scions are placed in the split understock, it is important to keep the scion humid to permit callusing. The split stock usually holds the scion firm, but it may be wrapped with string, rubber ties, or 3⁄8-inch electrician’s tape. The graft may be covered with moist, sterile sand. To maintain the humidity around the scion cover the graft with a 1-gallon or larger bleach bottle or other opaque container with the bottom cut out or with a large-mouthed brown jar. Burlap or a brown paper bag will be needed to cover a 1-gallon milk jug (bottom cut out) or a large-mouthed jar to protect the graft from sun and excessive heat buildup. Be sure to label the graft, or you will have to wait until the camellia blooms to identify it.

The time for callus formation and bud break varies with the variety and season. It is important to have good callus formation uniting the cambiums of the scion and stock before uncovering the graft. It is best to lower the humidity under the bottle or a jar in stages. Removing the lid of the bottle or milk jug or raising the jar an inch lowers the humidity and allows some light to enter at the same time. When the bottle lid is removed, the light may cause the shoot to grow out through the lid area.

Do not permit the young plant to wilt before it becomes acclimated to light and lowered humidity. When to remove the cover over the graft is a matter of experience. Protect the young graft from mechanical damage the first year. Mulch with pine straw and remove sucker sprouts of the understock as they develop. Surrogate, bark, nurse-seed, and wedge grafts have also been used with camellias. Consult camellia literature or experts for one of these. Cleft grafting is easy once you have observed it being done properly by an experienced propagator.

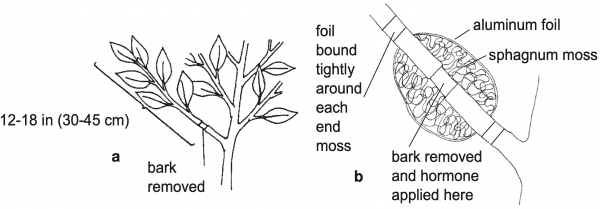

Propagation By Air Layering

Camellias can be air layered in the spring after the new growth begins to harden. Select a healthy branch 1 to 2 feet in length from tip to base. The stem is usually between 3⁄8 to 5⁄8 inch in diameter near the base. Various methods of wounding are practiced. One method is to circle cut the bark with a sharp knife near the base of the branch in two places about 2 to 2½ inches apart. Girdle the stem and remove the bark between the circular cuts (Figure 6a). The girdled section of the branch is dusted with rooting compound and wrapped with moist sphagnum moss in the shape of a small football and tied in place. The sphagnum is wrapped with a layer of clear plastic wrap followed by a wrap of aluminum foil. Tightly secure the foil with string above and below the sphagnum to keep air out of the ball (Figure 6b).

Figure 6. Air layering a camellia

The air-layered plant can be severed below the ball in about 4 to 6 months and then potted in 2-gallon containers and given protection for the first winter. Only vigorous growing camellias should be air layered, since most slow-growing camellias are usually cleft grafted to vigorous understock to improve their relative rate of growth.

Container-Grown Plants

Camellias are adaptable to growing in 1- to 5-gallon plastic containers with drainage holes. The potting medium should also provide good drainage. A mixture of 1⁄3 soil, 1⁄3 sand, and 1⁄3 organic matter (Perlite or fine pine bark) is excellent for growing camellias. Other media compositions that have been used are (1) 80 percent fine pine bark and 20 percent river sand plus dolomitic limestone, cow manure, and trace elements; (2) 3 parts fine pine bark and 1 part Perlite and sandy top soil; (3) 2 parts forest humus and 1 part sandy loam; (4) 3 parts fine pine bark, 1 part sand, ½ part soil, and ½ part loose peat moss; and (5) 50 percent peat moss and 50 percent sandy loam. Do not plant rooted cuttings or germinated seedlings too deep. Firm the medium to reduce air pockets.

Watering is essential during the active growing season and is required frequently during drought conditions. However, watering increases the loss of nutrients from the medium. Containers with sand and pine bark mulch can be fertilized with a weak solution of fish emulsion (5-2-2) or (5-1-1) applied weekly without fear of burning the young plants. Slow-release fertilizers are widely used for container plants as are cottonseed meal and other organic fertilizers. Slow-release fertilizers can be mixed with any medium before planting. Liquid fertilizers are also recommended. Light fertilizer applications biweekly during the growing season are preferred to heavy, less frequent applications. Reduce fertilization in late summer and fall as camellias go into the dormant season of winter. Soil pH is important in container-grown plants and is kept in the 5.5 to 6.5 pH range for camellias.

After a few years, container plants become root-bound and require repotting with the same type fresh medium. If the roots are concentrated on the outside of the ball, repotting to larger containers is advisable. The soil is washed from the roots and the pruning of the root ball is carried out. Using the same soil mixture, firm and thoroughly water. Repotting is best in early spring before new growth starts. Container plants require winter protection to avoid damage from freezing temperatures. In mild climates, container-grown camellias can be protected by large quantities of mulch in an area sheltered from the wind. In colder regions, plants require the protection of a sun porch or a cool greenhouse.

Problems

Diseases

Flower Blights

Camellia flower blight, or petal blight, is one of the biggest threats to camellia growth. Caused by the fungus Ciborinia camelliae, formerly Sclerotinia camelliae, it infects only the flower tissue of camellias, does not spread from flower to flower, and is characterized by brown spots on the petals that spread rapidly to engulf the whole bloom. Infected blooms fall to the ground and in time produce a sclerotium in the base of the bloom. These sclerotia are the source of survival of the fungus until the following year. Sclerotia may lie dormant in the soil up to 4 years. When warm and humid conditions occur, small, dime-sized, brownish-gray mushrooms, known as apothecia, are produced from the sclerotia to liberate the spores that are the infective stage. This produces another cycle of petal blight. A community effort is needed to control the disease since the spores can be carried by wind for half a mile or more. It is prevalent and most active in humid areas when the temperatures range between 45 degrees F and 70 degrees F during the mid- to late-season flowering period. Camellia petal blight does not infect the leaves, stems, or roots of camellias.

Some control can be obtained by sanitation measures when all blooms are picked up, including petals and blooms lodged in branches, and destroyed by burning or by sending them to a garbage landfill. Drenches of pentachloronitrobenzene (PCNB—75 percent wettable powder) applied around the plant and to the mulch of camellias inhibit the development of the infective spores and the apothecia of the fungus. Start the treatment in early December and continue every 4 to 6 weeks through March. Spray or drench to wet the soil and mulch thoroughly with 2 gallons per 20 square feet.

Botrytis flower blight (gray mold) usually infects inside blooms that have been damaged by frost, water dripping from above, water sprays, high humidity, or high temperatures. Lack of good air circulation is also a contributor. Botrytis symptoms are very similar to petal blight in the bloom, except that Botrytis does not engulf the bloom rapidly. Botrytis-infected blooms do not have the slimy texture associated with petal blight. Frequently, a gray, powdery fungal growth appears on the flowers, particularly on the stamens or at the base of the blooms.

The abundance of spores spreads the fungus from bloom to bloom, damaging each one it touches. It is not a serious problem unless ignored or neglected. Sanitation is the best prevention. Be sure your plants have good air circulation. Your county Extension agent can recommend fungicides, such as thiophanate-methyl or triadimefon that will control Botrytis.

Root Rot

Root rot can be caused by one of two fungi. Phytophthora cinnamomi attacks C. japonica and C. reticulata under certain conditions. The fungus does not attack C. sasanqua and C. oleifera. It can be prevented with a drench of metalaxyl applied once every 6 months. Root rot caused by Cylindrocladium crotalariae often results from adding sand or silt contaminated with the fungus. A clean soil mix will solve the problem. The fungus rarely attacks mature and established plants.

Camellia Dieback

The fungus Glomerella cingulata causes camellia dieback. Symptoms are the sudden wilting of a twig of new growth or the development of cankers on a limb or trunk. Control by cutting off infected, wilted areas down to clean, uninvaded wood. Infected wood is brown with an orange cast. Sterilize the pruners with isopropyl alcohol between cuts. Dieback is spread when contaminated water splashes on new growth or a plant wound, such as a fresh leaf scar. C. sasanqua is more susceptible to dieback than is C. japonica. It is more prevalent in humid areas. Spray thiophanate-methyl at labeled rates every 2 or 3 weeks beginning in early spring and continue fungicide applications into June.

Viruses

Some viruslike variegation in camellia flowers and leaves is genetic, while yellow leaf viruses transmitted by grafting cause mottle and other flower and leaf variegation. The degree of variegation in both flowers and leaves varies from year to year on the same plant. This is caused by the uneven distribution of the virus in the plant and the varying environmental conditions of each season. Leaves with yellow leaf mottle infection are less cold hardy and tend to sunburn more easily than healthy plant foliage. Avoid viruses by grafting to nonvariegated understock of C. sasanqua and C. japonica. Also, do not collect scion wood for grafting from camellias with mottled or variegated leaves. The flower striping as seen in camellias Herme, Elizabeth, and Lady Van Sittart is genetic and is desirably transmitted by grafting.

Leaf Gall

This disease is caused by the fungus Exobasidium camelliae and is most common on C. sasanqua. Infected leaves thicken and enlarge with the first flush of growth in the spring. Usually, only a few leaves and twigs are infected on each plant. Control by removing the thickened leaves when they first appear and destroying them before the fungus sporulates and infects the plants for next year’s growth.

Environmental (Physiological) Problems

Camellia Scab

Not a fungus disease, scab refers to several types of damage to plant leaves—black spot, white spot, angular spot, concentric spot, corky excrescence, scurf, and sasanqua spot. Scab is the result of improper water relations in the plant and too much hot sun. The unsightly condition of the foliage is of more concern to the grower than the damage is to the camellia. To prevent scab, plant camellias in well-drained soil, in semi-shade locations. Water during dry periods in spring, summer, fall, and winter.

Sunburn

This condition, which is the yellowing or bronzing of leaves exposed to the hot sun, is a common problem. Causes include moving plants from shaded to more exposed sites, removing overhanging branches, underwatering of new transplants, or setting out plants with inadequate root systems relative to the aboveground plant.

Fertilizer Burn

This problem results from overfertilization or inadequate mulching before fertilizing and from underwatering.

Lichens

Lichens are gray-green to green mossy growths on the stems of old, neglected camellias. The lichen is a combination of a fungus and an alga that grows symbiotically. They are not parasitic to the camellia. Affected plants usually need fertilizing, watering, and mulching for better growing conditions. Spraying with a copper fungicide will kill unsightly lichens.

Bud Drop of Camellias

Bud drop is a fairly common problem that causes concern among camellia growers at all levels of expertise. Because camellias bloom during the winter months, they are susceptible to wide swings of temperature that are part of the “normal” winter weather in the Southeast. Freezing temperatures can cause buds to drop before opening, especially with young plants and some varieties that are cold sensitive, such as hybrids of C. reticulata. Long periods of hot weather in the early fall can cause buds to drop off in late fall. In the spring, late-blooming varieties may drop their buds before opening as the temperatures begin to rise and initiate shoot growth. Avoid planting varieties that open too late or gibbing the flower buds to enjoy them earlier in the season. New growers may not realize that all camellia varieties do not perform equally well in all locations.

Wide fluctuations in moisture can also cause dropping of flower buds. Camellias do best when moisture is sufficient and uniform. Bud drop can be caused by soil that is either too wet or too dry. Neglect of any cultural factor—soil, nutrition, water, drainage, shade—can cause bud drop. Any type of stress on the plant can result in bud drop. If this condition occurs year after year, it may be a varietal problem, which can be resolved by grafting to another rootstock or transplanting the plant to another location. A camellia bud mite may be the problem. Early blooming varieties or gibbing for earlier blooms can prevent mite damage. Spraying plants with a miticide, applied as soon as flower buds have set, will usually control flower bud mites.

Insects

Scale Insects

Scale insects are the most important pests of camellias. They have sucking mouthparts and feed by piercing the leaves and twigs and utilizing the plant juices for food. This stunts and weakens the camellia and hurts the appearance of the foliage. Tea scale (Fioriniae theae) is the most damaging scale insect. Yellow splotches appear on the upper side of the leaves, while the underside is covered with a cottony mass.

The adult males have a white, waxy covering and are more conspicuous than the dark brown, oval-shaped females, which are about 1⁄20 of an inch long. The female lays her eggs under the scale covering. The eggs hatch in 1 to 2 weeks. The newly hatched scale, known as a crawler, moves about the plant and after a week inserts its mouthparts into succulent new-plant tissue. The adult stage is usually attained in 5 to 11 weeks after egg hatch, so there are several generations produced each year.

Camellia scale (Pulvinaria floccifera) is the other common scale pest of camellias. Proper culture and the use of insecticidal sprays can control scale insects.

Horticultural oil sprays are environmentally friendly and nontoxic to humans and pets. Systemic insecticides, such as dimethoate or acephate, can be applied to control or eliminate scale insects. Sprays of label-directed concentrations can be sprayed on the plants. Since they are systemic, they kill the sucking-type insects without direct contact. Due to the insect cycle, a second spray may be required a few weeks later. The first application kills the crawlers, females, and males, while the second spray kills the crawlers that have hatched since the first spray. Always use insecticides strictly according to the labeled instructions.

Other Insect Pests

Leaf-eating bugs, spider mites, aphids, mealy bugs, and white flies are all readily controlled with insecticides, once the pest has been identified. None of the insect pests are life threatening to the plant (except scale insects) unless they are ignored and left untreated. They can then become severe, but this seldom happens. Your county Extension agent can identify the insect and recommend the appropriate control measures.

References

The Camellia Journal, volumes 35-36 and 50-54. American Camellia Society, Fort Valley, GA.

Chidamian, C. 1959. Camellias for Everyone. Doubleday & Co., N.Y. 191 pg.

Chuang-xing, Ye. 1997. Classification in the genus Camellia L. The American Camellia Yearbook. Pg. 9-23.

Edgar, L.A. 1991. Camellias, the Complete Guide. Crowood Press, London. 224 pg.

Ellison, D. 1997. Camellias, a Photo Dictionary.(1,000 color photos of camellias). Flora Publi. Intnat’l. Ltd., Brisbane, Australia. 160 pg.

Feathers, D.L., and M.H. Brown. 1978. The Camellia, Its History, Culture, Genetics, and a Look Into Its Future Development. American Camellia Society. R.L. Bryan, Columbia, SC. (Under revision by A.C.S.) 476 pg.

Galle, F.C. 1979. Azaleas and Camellias. A.B. Morse, Burlington, IL. 48 pg.

Gonos, A.A., and S. Bracci. 1999. Camellia Nomenclature. Southern California Camellia Society. 184 pg.

Griffin, F., Sr. 1964. Camellian, A Compilation of Authoritative Information on Camellia Culture. Vogue Press, Columbia, SC. 245 pg.

Macoboy, S. 1998. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Camellias. (More than 1,000 color photos of camellias.) Timber Press, Portland, OR. 304 pg.

Napier, J.M. 1953. Growing camellias as a hobby. Clemson Agric. Ext. Serv. Circular 377. 32 pg.

Trehane, J. 1998. Camellias, The Complete Guide to Their Cultivation and Use. (More than 100 illustrations for uses of camellias). Timber Press, Portland, OR. 176 pg.

- Ville de Nantes

- Snowman

- Winfred Womack

- Maureen Connolly

- Lady Kay Red Variegated

- Kate Mallory

- Fashionata

- Marie Bracey

- Lady Kay

Download a PDF of The Culture of Camellias: The State Flower of Alabama, ANR-0202.