*This is an excerpt from Beef Conformation Basics, ANR-1452.

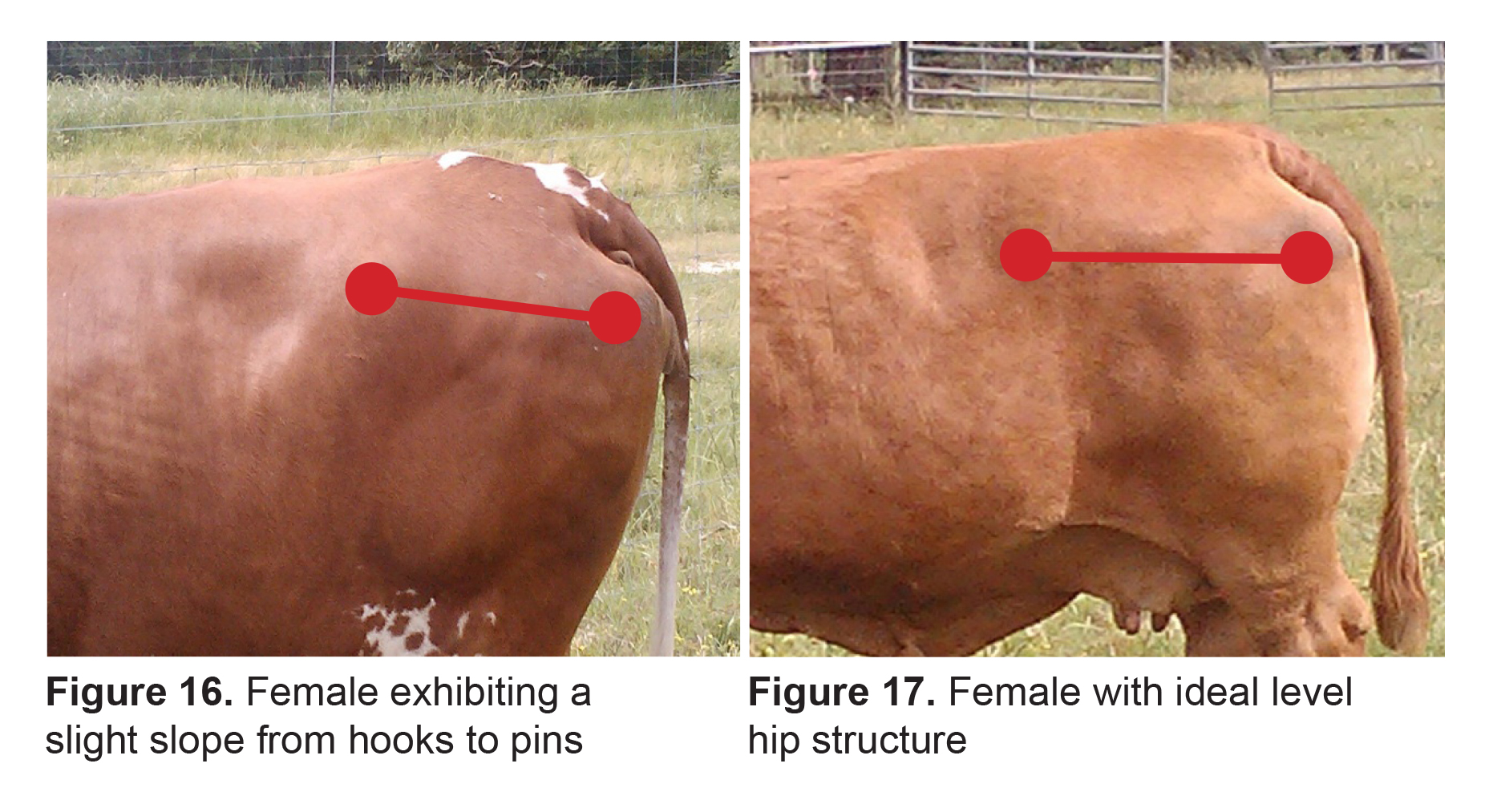

The two points of reference to be aware of in evaluating the hip are the hooks and pins. Both points are identified in Figures 16 and 17, with the pins being the point beneath the tail head. Although some breeds, such as those influenced by Brahman genetics, are less likely to be level, the ideal beef animal would be nearly level from hooks to pins. Although it is not always the case, a level hip normally equals a longer, more muscular hip if for no other reason than length itself. Also, a level hip is normally considered more eye-appealing. As the hip becomes less level, it can become shorter and be associated with other issues such as cattle having their hind legs placed too far beneath them.

Some producers have defended cattle with a minor slope from hooks to pins by saying these cattle have an advantage when it comes to calving and expelling afterbirth. As long as the slope is not extreme, not much compromise is made in regard to structural correctness.

One of the more problematic arrangements of the hip can be found when cattle are higher at their pins than at their hooks. In females, this can lead to problems with calving and expelling afterbirth. Although the calving problem is only expressed in females, breeding bulls exhibiting this characteristic should be selected against as well in order to not perpetuate the characteristic.

Related Topics

*This is an excerpt from Beef Conformation Basics, ANR-1452.

From the front, cattle whose hooves are faced forward are ideal. The steer shown in figure 14 is a good example of both hooves pointing directly forward. Much as it is with the hind legs, some angle in the outward direction is acceptable, and any angle of 10 degrees or less is accepted as normal. Functionality of the front end is normally not compromised until the outward turn approaches 30 degrees or more. Cattle with this condition are commonly referred to as being splay footed. Cattle that are splay footed can usually also be classified as being knock kneed. Figure 15 is a good example of a heifer having both of these conditions.

Another condition in beef cattle concerning the front limbs occurs when the front hooves point inward toward each other. Cattle exhibiting this condition are said to be pigeon toed. This condition is rarely seen and is detrimental to the functionality of the forelimbs.

*This is an excerpt from Beef Conformation Basics, ANR-1452.

When evaluating beef cattle from the rear, hooves of the animal should point forward. However, that is not the case in a large number of beef cattle. In many instances, the hooves of the hind legs turn outward instead of pointing forward. Cattle with this condition are commonly referred to as being cow hocked. The hocks are also usually turned inward and can be closer together than the hooves in some extreme cases. In milder cases, cattle are unhindered in terms of normal productivity. The steer shown in Figure 12 is slightly cow hocked but would be considered normal, as anything less than a 10-degree angle is considered as normal. In some extreme cases, this condition can result in uneven toe growth and wear. Cattle more extreme in this condition are usually very light muscled as is the heifer shown in Figure 13.

Less commonly seen in beef cattle is the condition known as bowleggedness. This term is used to describe cattle whose hooves are pointed inward on their hind limbs. Though this term may also be used to describe a similar condition in the front limbs, it usually describes cattle that are farther apart at the hocks than at their hooves. This condition is considered more serious in terms of inhibiting proper mobility and is far less common in comparison to the cow-hocked condition.

*This is an excerpt from Beef Conformation Basics, ANR-1452.

The alignment of joints in the front leg also plays a considerable role in the structural correctness and mobility of a beef animal. More than 50 percent of the animal’s weight must be supported and carried by its front two legs. In order for that to be done effectively, the joints must be able to provide some shock absorption and allow considerable range of motion. The ideal angle for the scapula, or shoulder, in relation to the ground

is approximately 45 degrees. This angle allows for the appropriate range of motion and is usually associated with the front legs being placed squarely beneath the scapula. As the angle becomes larger, range of motion is restricted, and the result is the animal taking shorter, less efficient steps. Larger angles can also affect the knee and result in the animal being buck kneed. This condition occurs when the animal’s knee is pitched forward in relation to the rest of the foreleg. This condition can also be associated with cattle being too straight in their front pasterns.

When the angle of the scapula is too small, the usual result is the animal being calf kneed. This condition occurs when the knee is positioned behind the outline created by the front leg. This condition is less damaging to the front leg function than is the buck-kneed condition. In some situations, such as when cattle are being confined on concrete, this condition may be considered more ideal as it provides more cushion for the front limb. Figure 9 shows the joint alignments seen with these conditions.

Evaluating the slope of the shoulder can be one of the more challenging tasks when it comes to gauging soundness of beef cattle. The point of shoulder and

the spine of the scapula are two of the most important points to consider when making this evaluation. By distinguishing these two points and evaluating their relation to the ground, a reasonable assessment can be made as to what the slope actually is. Another helpful way to visualize the slope is to imagine a line from the point of shoulder straight down to the ground. As cattle become more vertical in terms of their scapula, the line from the point of shoulder straight down to the ground will be closer to the front leg itself. Other indicators as to whether an animal is too straight shouldered include the top of the scapula being visible above the animal’s top line and shorter, more restricted steps when the animal moves.

The two animals in Figures 10 and 11 are examples of some structural differences when it comes to slope of shoulder and forelimb alignment. The calf in Figure 10 is considerably more vertical in terms of slope of shoulder as demonstrated by the line connecting the spine of the scapula, point of shoulder, and the ground. The line going from point of shoulder directly to the ground also indicates a steep shoulder as it is very close to the outline of the front leg. The female in Figure 11 is closer to ideal in regard to slope of shoulder and has considerably more space between point of shoulder and her front leg.