About Us

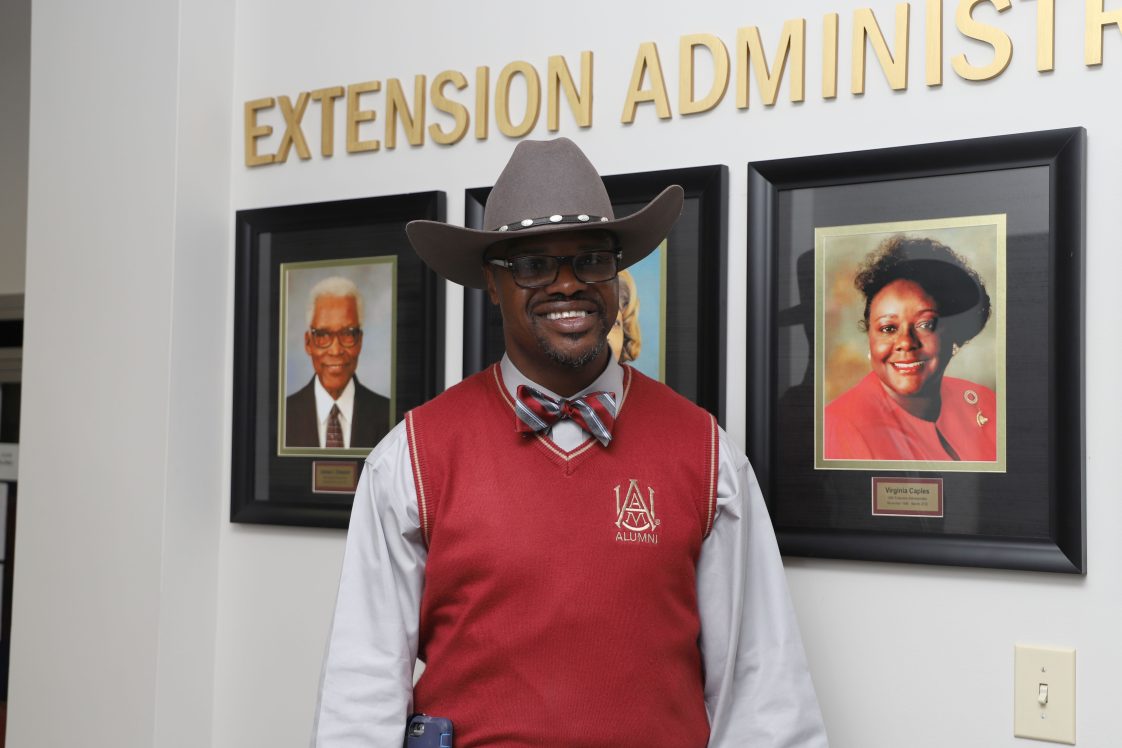

ALABAMA A&M UNIVERSITY, Ala. — Tyrone Smith has a unique perspective on Cooperative Extension. He has worked for all three land-grant institutions in Alabama: Alabama A&M University (AAMU), Auburn University and Tuskegee University. Today, he is the assistant director for agriculture and natural resources at Tuskegee University Extension.

He also worked as a regional 4-H liaison specialist at the United States Department of Agriculture in Washington, D.C. He served nine states and 19 military installations, including West Point in New York. However, the Alabama Cooperative Extension System at AAMU laid the foundation for his career in Extension.

An Early Start

“There was a class called Extension Methods and Dr. Dony Gapasin (former Extension specialist), taught that class in Carver Complex South,” Smith said. “Later it went over to the Dawson Building (current Cooperative Extension building). That class taught us the importance of Cooperative Extension and why it was relevant. He talked about the 1890s, the Smith-Lever and Morrill Acts and the Hatch Act — all those things that went into forming Cooperative Extension — the whole method of taking the university to the people.”

Smith had a revelation after taking the Extension Methods class.

“I think I might like doing that,” he said. “I like working with people, I like what the university is doing with the research and I like breaking things down into layman’s terms so the people can understand.”

Smith eventually became an agent assistant with the 1890 Cooperative Extension program at AAMU. At that time, he implemented agriculture, natural resources and 4-H youth development programs for residents in Madison and Jackson counties.

Life at the County Level

As an agent assistant much of his daily work involved answering phones.

Smith said the county office connects agents to the people.

“That’s why we were in the county offices and not at the universities,” Smith said. “When people needed help — when their plant was dying or their goat was sick — I would field those calls. If I didn’t know the answer, I would call the university. We had animal scientists, plant scientists, soil scientists and horticulturists on staff there. Then we would give our recommendations (to the consumer).”

Smith said the beauty of Extension was that everything they gave out was research-based.

“So, it couldn’t be my opinion, what I thought or some of Grandma’s remedies,” he said. “We were that door of taking the university to the people.”

Smith also worked with young people.

“We worked with youth ages nine to 19 in our inner city schools in Huntsville and Jackson County in our rural schools,” Smith said. “Each program looked different because in Cooperative Extension you work or plan with people — not for people. There are different needs.”

The Court Decree

Smith was working for Alabama Extension when Knight v. Alabama first took effect. The historical case is more commonly known as the Alabama Higher Education Desegregation Lawsuit. This lawsuit was responsible for unifying Cooperative Extension programs at AAMU and Auburn University into the Alabama Cooperative Extension System, with Tuskegee cooperating.

He described how the court case changed Alabama Extension on the county level.

“After the lawsuit, the walls came down,” Smith said. “We (county staff) were in separate offices. So, after the lawsuit, we had to integrate the offices and now it’s one system. We were able to reach a broader spectrum (audience).”

Under the leadership of former 1890 Administrator Virginia Caples, Alabama Extension at AAMU established nine Urban Centers across Alabama. This was a change after serving only 12 north Alabama counties, whereas Auburn served the whole state and Tuskegee served the Blackbelt counties.

“Once the System came together, we fused all programs to serve all Alabamians,” Smith said. “From a programmatic standpoint, it allowed us to spread throughout the state, impact other people and open up different partnerships.”

Extension Impacts

Smith said Extension impacted his life through the opportunity to be a servant learner and help people find quality research information.

“In a time now with so much social media, so much information on the Internet and readily available — how do you, for lack of a better term — fact check that?,” Smith said. “Alabama Extension teaches you to make sure you have the facts before you make a recommendation. It has affected my whole decision-making process.”

Alabama Extension routinely documents how our programs and services affect the people we serve.

“We do impact statements,” Smith said. “We would write those monthly or annually to determine, ‘Where were you before you met us and where are you now because of us?’”

He used the example of working with a farmer with a low-producing bull. In this case, he would examine the producer’s livestock practices and systematically and strategically work with him or her to get them to a place where they were more productive.

“The producer would come back to me and say, ‘Thank you. Because of Alabama Extension, I am making more money now. Now I know what I am doing. I was self-taught or taught by my grandfather. But because of your workshop, now I can do better,’” Smith said.

Smith said the people employed by Extension want to meet people where they are and get them to where they want to be.

Discover Alabama Extension

Meeting people where they are is how Alabama Extension engages with its audiences to offer solutions to daily challenges. Extension educators are strong community partners, bringing practical ways to support homes, farms, people and communities.