Crop Production

For optimum performance and longevity, fruit trees must be initially trained to a desirable tree form. Annual pruning is necessary for deciduous fruit trees although the level and type of pruning varies among species.

Training Fruit Trees

If fruit growers expect to maintain consistent yields and high-quality fruit, they should train trees during the first 2 to 6 years of a planting, depending on the type of trees grown. Some growers plant fruit trees and wait for them to start producing. In the long run, this has shown to be an unsustainable practice. If the trees are properly trained initially, they will develop the desirable tree architecture and scaffold system to produce high yields of quality fruit. They will also require less corrective pruning in later years.

The best time to start training newly set trees is in the spring after growth begins. The main goal in training young fruit trees is to develop the proper number of wide-angled scaffold branches in a desirable arrangement along the trunk. These branches must be strong to support heavy crop loads and prevent splitting and breaking.

Training Systems for Fruit Trees

Numerous systems are being used worldwide for training and pruning fruit trees. Some tree fruits, such as citrus, require almost no training except for developing suitable young trees in the nursery. By contrast, temperate, deciduous tree fruits, such as apples and peaches, need proper training and subsequent pruning for maximum longevity and profitability.

Training systems include the following:

- The older, conventional, low-density systems that have been used on freestanding, large trees planted at wide spacings. Examples are the central leader and modified leader used for apples and pears and the vase or open-center system used for peaches and nectarines.

- The more recently established high-density systems that have involved the dwarf and semi-dwarf apple trees using size-controlling dwarfing rootstocks established along a 3- to 4-wire trellis.

- The recent trend toward smaller, more closely spaced, high-density plantings has resulted in several variations of the older training systems described above and several new ones, which may be referred to as high-density systems.

Among the more popular new training systems are the vertical or French axe and slender spindle, or its modification known as the tall spindle. These systems are being used to train apples grown at very high densities (400 to 1,000 or more trees per acre) and require dwarf to semi-dwarf trees with some type of tree support. All these systems are modifications of the central leader form of training.

To stimulate growth and build a large, strong framework to support future crops, portions of trees are cut back severely for several years in the medium-density central leader system, while in high-density systems, excessive growth is discouraged. Instead of a large, strong framework, a weak-framed tree is desirable. Very little pruning is done in the early years to achieve this structure in a system such as a tall spindle or French axe. The goal is to promote early fruiting, which will inhibit future growth. All high-density systems require a greater knowledge and understanding of plant growth and how the tree will respond to cuts. In early years, more attention is paid to training and positioning limbs than pruning them.

Some of the more popular training systems for tree fruits are described below.

Training Apple Trees: Central Leader Form

For freestanding or staked medium-density plantings of apples, the central leader tree (pyramidal or Christmas tree) form is preferred. This form helps maximize light penetration into the tree’s center and light distribution along and between trees (figure 1). To develop the central leader tree, prune newly set trees immediately after planting, before growth begins, to a height of 28 inches. This will force the first scaffold branches to develop at the desired height.

Figure 1. Central leader training system for apples and pears. Dotted lines represent branches that are removed. Source: Stebbins, R.L. 1980. Training and Pruning Apple and Pear Trees.

As young shoots begin growth in the spring, usually one or two shoots in the uppermost position near the pruning cut will grow straight upward. When these shoots are 8 to 12 inches long, select the strongest and straightest to continue upward growth as the leader. Remove the other competing shoots within 1 to 2 inches of the leader.

When the lower branches are 3 to 6 inches long, remove all branches lower than 20 inches from the soil line. Select three to five branches that are 4 to 8 inches apart, spiraling up and around the tree. These will form the first tier or whorl of branches. The first branch (or lowest branch) you select should be about 20 to 24 inches from the soil line.

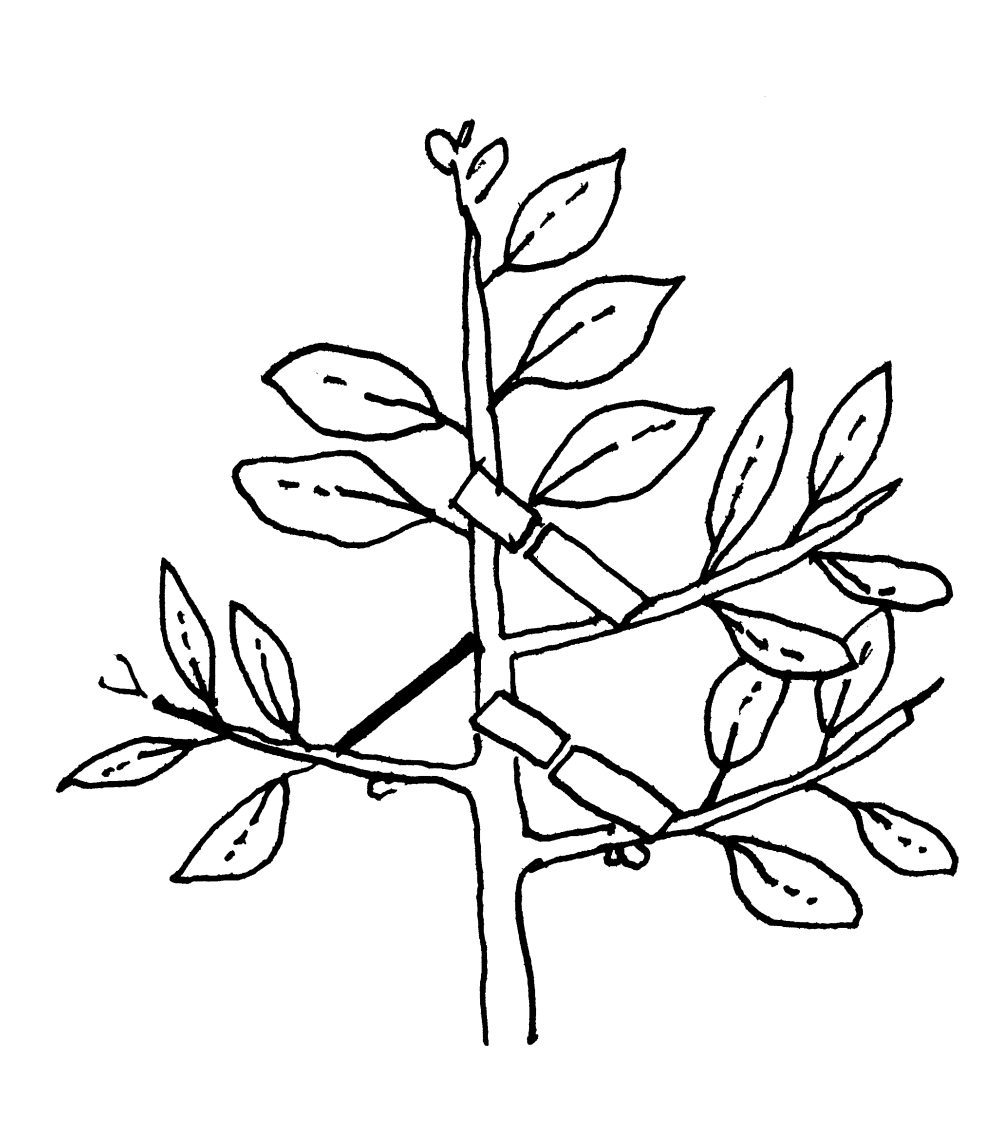

Train the selected branches to form a wide crotch angle by using spring-type wooden clothespins. Place these braces when the branches are 3 to 6 inches long and still succulent. Set the braces so that the branches form a 90-degree angle with the main axis of the tree (figure 2).

Figure 2. The small branches used to develop scaffolds must be trained while very small and rapidly growing—when they are 3 to 4 inches long and about 1⁄8 inch in diameter. After 6 to 8 weeks, at the end of the initial training period, the shoots may have reached ¼ to ½ inch in diameter.

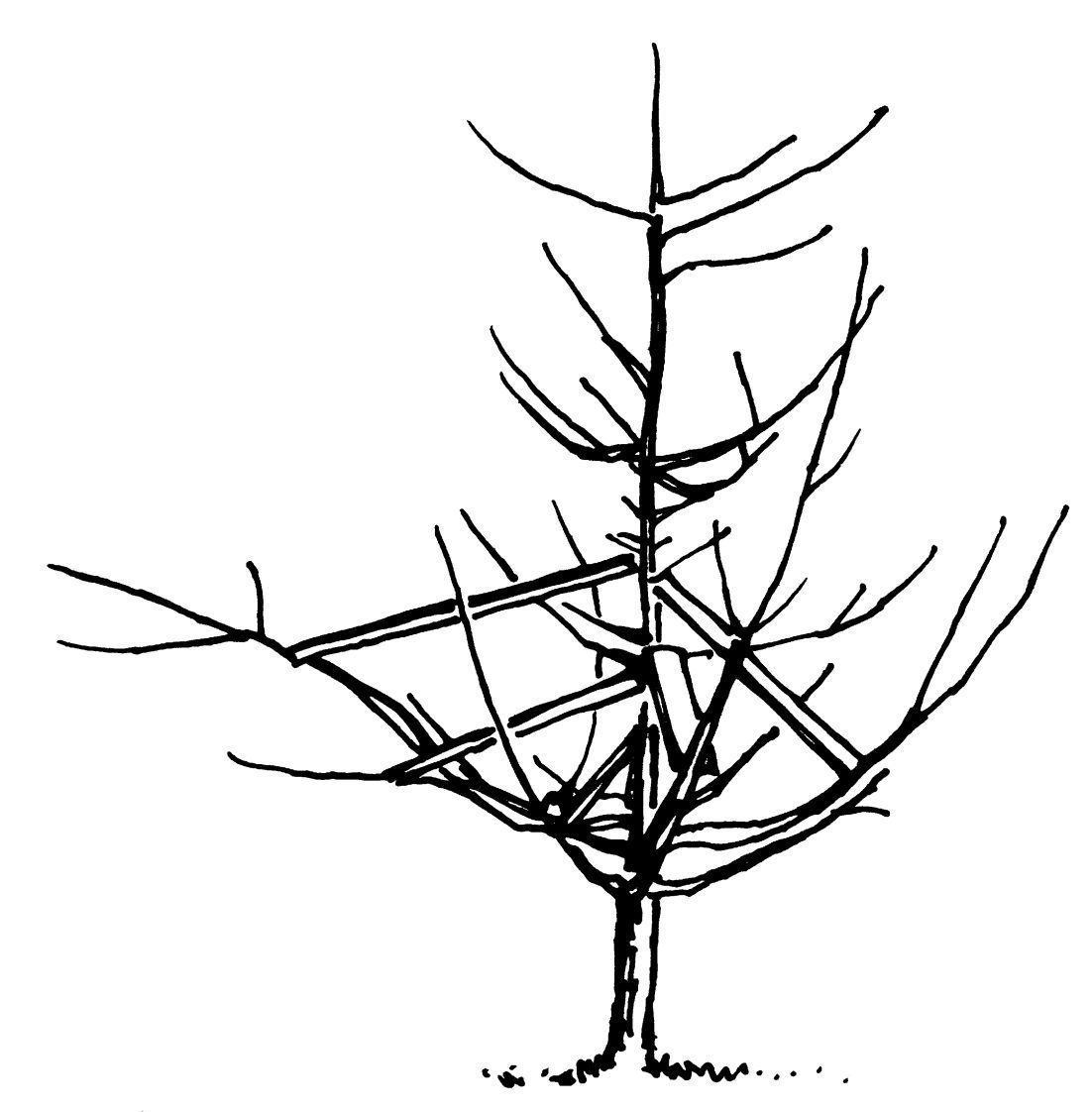

Remove the clothespins to prevent girdling when shoot tissue lignifies or hardens, usually within 2 months. Clothespins or other small devices are initial training aids and not substitutes for longer limb spreaders to be used later. Remove all other branches that begin to grow in this area so that they do not compete with the selected scaffold branches. Removing these competing branches will help develop the first tier or whorl of branches. Three or four tiers will usually be needed to form the ideal tree. The three to four scaffold limbs comprising the first tier should be arranged equally distant around the trunk and separated vertically along the trunk by 4 to 8 inches. Additional tiers of scaffolds should be developed so that they are positioned in the openings not occupied by scaffolds in the tier below. No scaffold should be closer than 36 inches above one another. Developing the third- or fourth-tier branches will take 3 to 4 years (figure 3). Use the same procedure to develop the first tier of branches to develop the second, third, and additional tiers of branches.

Figure 3. A bearing apple tree showing distribution of structural and fruiting branches in three developing tiers.

The branches that were forced to form a wide angle at their base will turn and grow upward as they elongate. Thus, after removing clothespins from newly formed scaffolds in midsummer of the first year, continue spreading branches using longer spreaders. If trees have grown sufficiently, place new spreaders on branches in late summer of the first growing season. Otherwise, position new spreaders on branches during the first winter or at the end of the second and possibly third growing seasons.

Tree development will dictate when you should add more spreaders. Initially, brace branches to form a 45-degree angle with the main axis of the tree. Spreading the limbs to a more horizontal position at this time encourages the development of undesirable, strong, vertical shoots on the tops of scaffold limbs. As branches become large enough to fill their allotted space, spread them to about a 60-degree angle from the central leader. Use the spreaders for one and possibly two or more seasons (figure 3). Remove suckers arising from the trunk and scaffold branches two or three times during the growing season by rubbing off the tender shoots.

In some instances, a side branch will not develop at the desired location on the trunk of a tree. If a scaffold branch is needed in a particular spot on the tree, you can use MaxCell or Promalin to induce new branch development.

Trellising Apples

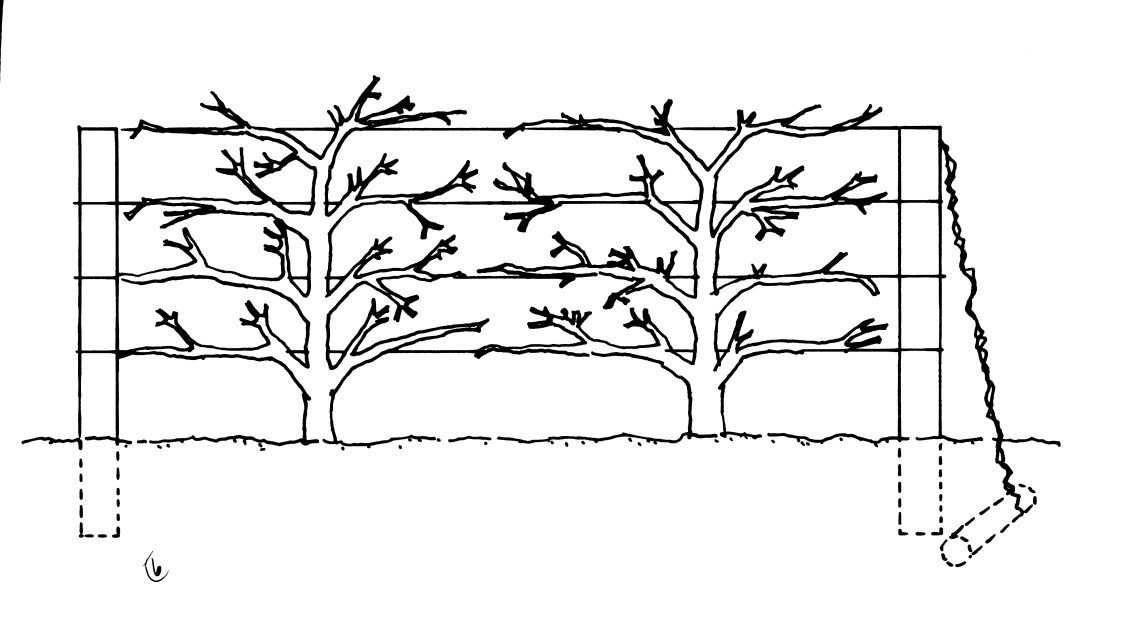

Whether you are a home orchardist or a commercial grower, you can use one of the newer technologies for training and trellising apples to improve yield and quality. When apples are grown on dwarfing rootstocks, the trees must be supported. Training them to a wire trellis permits high-density planting and early production of high-quality fruit.

One of the more popular trellis systems used is the conventional three- to four-wire trellis system 6 to 6½ feet high (figure 4). Use 8- to 9-foot treated posts spaced 12 to 16 feet apart, depending upon tree spacing. Use No. 9 smooth wire or plastic continuous filament and fasten the bottom wire to each post 20 inches above ground. Some growers prefer to drill holes in the posts at the proper height and run the wire through these holes. This method works well also. Locate the top wire 74 inches above the ground. Fasten one of the other two wires 18 inches above the bottom wire and the other one 18 inches below the top wire. For a three-wire trellis, fasten the middle wire between the top and bottom wires, about 26 to 27 inches from each other. Securely anchor end posts by bracing or tying them with a strong wire fastened to a deadman brace buried in the ground. A deadman brace can be a post, concrete, or other heavy material.

Figure 4. Four-wire apple trellis. End posts are usually 4 to 8 inches in diameter for short rows but may need to be 8 to 12 inches in diameter for very long rows. Line posts are usually 2 to 3 inches in diameter.

Use recommended varieties of apples grafted onto fire blight tolerant rootstocks (see Extension publication ANR-0053-G, “Recommended Rootstocks”). Plant trees 8 feet apart (two between each post) with trellises 12 to 16 feet apart. This gives 340 to 454 trees per acre. Other suggested spacings are trees 6 feet apart with trellises 12 to 16 feet apart. This provides 518 to 605 trees per acre. A wider spacing between rows of 16 feet allows for greater ease of machinery movement and general management of the orchard. This is especially true where the somewhat more vigorous rootstocks, such as G.30, G.202, and G.969, are used. This wider between-row spacing is suggested for large commercial operations.

Develop a tree with eight major branches—four each way on the wires. Develop six branches in the same fashion for a three-wire trellis. Tie each branch to a wire. Train the branches on the wires at a 90-degree angle or a 65-degree angle from the trunk. Training at a 65-degree angle from the trunk is the best approach. To do this, cut the center leader about 4 inches below each wire as it grows upward. Select the two branches needed and tie them to each wire. Remove other competing shoots along the trunk, leaving only the leader and the two branches needed for the wires.

Use summer pruning to develop the spur-fruiting system on the trellis framework during the first 3 to 4 years. Remove current growth not needed for branch development along scaffolds (if upright) or cut back current growth to two or three buds between July 15 and August 1 to promote the formation of fruiting spurs and to permit full light exposure for optimum fruit color. Keep small branches every 12 to 15 inches on each side of the scaffolds. As trees age, thin out some of the fruiting branches where they are crowded. Depending upon the scion variety and rootstock combination, you can expect 50 to 200 pounds of apples per plant during the sixth growing season.

Training Apple Trees: Tall Spindle Trellis

The tall spindle system is the best trellis system for apple production, which can provide early returns to the grower and has been successfully utilized in new plantings. The tall spindle depends on utilizing well-feathered trees that can produce a crop the year after planting and continue to increase fruiting in the immediate subsequent years. The tall spindle was developed as an offshoot of the slender spindle training system to take advantage of increased canopy volume by increasing tree height.

There are several important components in the development of the tall spindle training system: (1) plantings must utilize high densities (800 to 1,500 trees per acre); (2) fully dwarfing rootstocks such as B.10, G.41, G.16 must be used; (3) nursery trees must have 10 to 15 feathers; (4) minimal pruning occurs at planting; (5) feathers (branches) are bent (tied) below horizontal immediately after planting; (6) permanent scaffold branches are not allowed to develop; (7) branches are renewed as they get too large.

Successful training of apple trees to a tall spindle trellis consists of the following steps: Plant highly feathered trees (10 to 15 feathers) at a spacing of 3 to 4 feet by 11 to 12 feet. Adjust graft union to 4 to 6 inches above soil level. Remove all feathers below 24 inches using a flush cut. Do not head the leader or the feathers. Remove any feathers that are larger than two-thirds the diameter of the leader at the point of insertion.

When the branches are 3 to 4 inches long, rub off the second and third shoots below the new leader shoot to eliminate competitors to the leader shoot.

Install a 3-wire trellis support system that will allow the tree to be supported to 10 feet (3 meters) in height. Attach the trees to the support system with a permanent tree tie above the first tier of feathers, leaving a 2-inch-diameter loop to allow for trunk growth. Tie down each feather longer than 10 inches to a pendant position below the horizontal.

During the first dormant season (second growing season), do not head the leader or prune branches unless there are scaffolds more than half the diameter of the central axis. When branches reach 4 to 6 inches of growth, pinch the lateral shoots in the top fourth of last year’s leader growth, removing about 2 inches of growth, including the terminal bud and 4 to 5 young leaves. Tie the developing leader to the support system with a permanent tie (figure 5).

Figure 5. Tall spindle trained apple at the Chilton Research and Extension Center, Clanton, Alabama, during the second growing season.

Vigorous branches that grew more than two-thirds the diameter of the leader should be removed (using a beveled cut) during the second dormant season. Use the permanent tie to secure the developing leader to the support trellis. In late summer, apply summer pruning to promote light interception and improve fruit color development.

Continue to remove overly vigorous limbs that are more than two-thirds the diameter of the leader using a bevel cut during the fourth growing season. Do not head the leader. Tie the developing leader to the support system with a permanent tie at the top of the wire and lightly summer prune to encourage good light penetration and fruit color in late summer.

For an established mature apple tree (fifth growing season and beyond), cut the leader back to a fruitful side branch to limit the tree’s height. Annually start removing at least two limbs, including the lower-tier scaffolds that are more than two-thirds the diameter of the leader, using a bevel cut. Columnarize the branches by removing any side branches that develop. Remove any limbs larger than 1 inch in diameter in the upper 2 feet of the tree.

Training Pear Trees: Modified Leader Form

Pear trees can be trained using the central leader system described above for apples (figure 6). The central leader system is especially useful for trees purchased on rootstocks, such as Quince A, Quince A plus Old Home pear interstem, or certain Old Home × Farmingdale hybrids, which tend to produce a semidwarf tree. However, when grown in the Southeast, Quince A and Old Home stocks are susceptible to fire blight or other problems and have not been used extensively. The most popular and blight-resistant stock used for pears in the southeastern area is Calleryana pear, Pyrus calleryana. This is a vigorous stock that results in the development of a large, normal-sized pear tree capable of producing 10 to 20 bushels or more.

Figure 6. Central leader–trained pear trees

Because of the large size of the tree generally grown in the Southeast, the central leader form of training may require some modification to compensate for the vigor and the greater problems with fire blight. Fire blight may more easily destroy a central leader tree by attacking the trunk than it will a multibranched modified leader tree form.

The other alternative to the system described for apples involves using a modified central leader form. Develop this form by pruning the young tree to a height of 28 inches at planting time. Select four to six wide-angled branches during or at the end of the first year for use as the primary scaffolds and remove all other growth. These branches should be 4 to 12 inches apart, beginning with the lowest branch 20 inches from the ground and spiraling upward around the trunk. You may have to wait until the second year to select all the branches.

Using clothespins and spreaders is not strictly necessary when training hard pear varieties such as Orient and Baldwin. However, early spreading and later branch spreading will result in better-structured trees. To properly train trees, head back primary scaffold branches and vigorous shoots each year for the first several years. Use the same methods as described for apples. Head back the primary scaffolds to a point where the next whorl of branches is desired. Thin out other shoots along these scaffolds and leave them unheaded. You may have to head back very vigorous side shoots.

Asian pears are reportedly smaller-growing trees than standard pears but may have equal or worse fire blight problems, depending on the variety and management. Therefore, a modified leader form is best for this more recently introduced type of pear. Some growers also advocate open-center training, which is used for peach trees. Because branches of most Asian pears tend to grow straight upward, early spreading with clothespins and later branch spreading should prove beneficial.

Training Peach and Nectarine Trees: Open-Center and Quad Forms

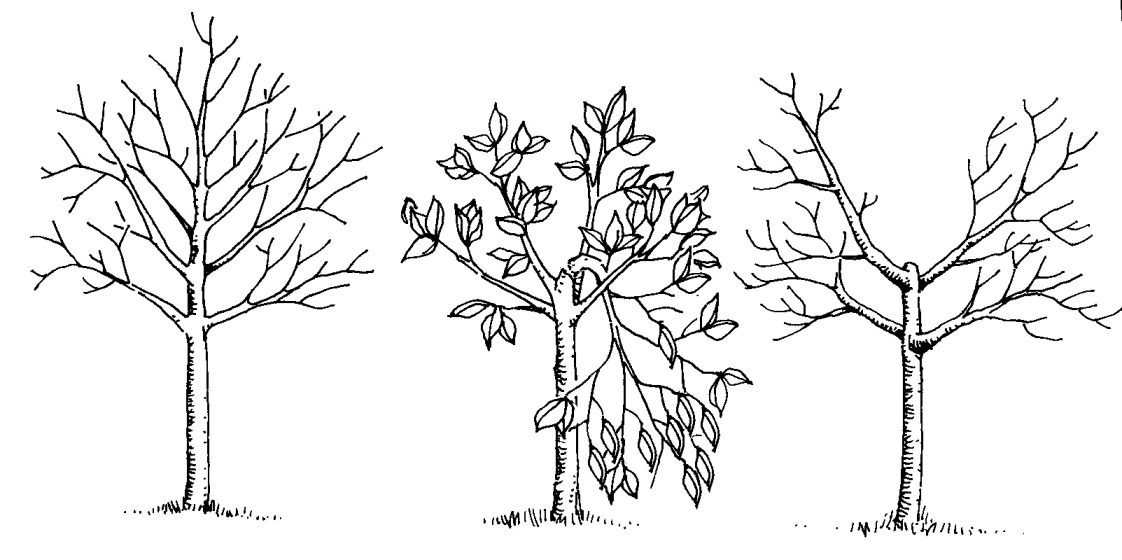

Peach and nectarine trees should be trained to a three-or four-limb open-center (figure 7) or quad form system. The quad is a modified form of the open-center system in which four scaffolds are selected for the framework and only fruiting wood is retained on these scaffolds. Select three to four shoots that are equally spaced around the trunk to be used as the major scaffold branches. Ideally, these shoots should be positioned at or near the same height on the trunk, with no more than 3 to 4 inches separating the uppermost and lowermost shoots. Most commonly, these shoots are selected anytime during the first growing season after the shoots are 12 to 18 inches long and you have removed excess shoots. This approach does not always result in the desirable wide-angled scaffolds.

Figure 7. Open center peaches

One of the best methods for early training involves allowing newly planted trees to grow unpruned for some 2 to 3 months or until shoots reach 24 to 36 inches in length (figure 8). Usually, one or two leaders grow straight up, and several lower branches develop with wide angles. At this time, remove the upper one-half to two-thirds of the leader(s). Select three to four of the most desirable lower wide-angled branches for the permanent scaffolds and remove all excess shoots. Recut the leader and some of its branches every 4 to 8 weeks to allow the lower selected branches to develop properly. During late winter to early spring of the next year, remove the pruned leader about ½ to 1 inch above the uppermost scaffold branch.

Figure 8 (A,B,C). Peach training sequence for scaffold development first growing season for open-center or quad tree form. A: Young tree in early summer of first season just before breaking or cutting developing central leader; B: Same tree shown in A after breaking over central leader; C: Same tree in A at end of first season with four well-developed scaffold branches.

Training Plum Trees

Plum trees can be trained using a modified leader or open-center system. The open-center system, as described for peaches, is preferred in the Southeast.

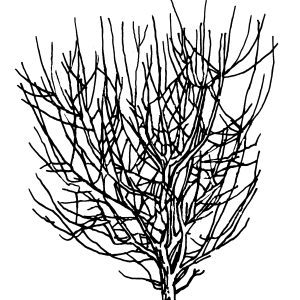

Training Figs

Because fig plants are periodically frozen severely, often to the soil line, a tree form of training using a single trunk is not recommended. Maintaining a bush form is generally best.

Develop a plant with 6 to 8 dominant branches arising close to the ground. Control height at 7 to 8 feet for harvest without a ladder, or allow trees to grow to 10 to 15 feet for harvest with a ladder. Keep the center of the plant open.

Pruning Bearing Fruit Plants

Annual pruning of fruit trees and vines stimulates the growth of desirable fruit-bearing wood throughout the plant. A balance between fertilizer applications and pruning to maintain moderate growth will result in more fruit bud formation. When heavy pruning is necessary to control growth, reduce applications of nitrogen fertilizer somewhat below the recommended rates for certain fruits, especially apples and pears. The primary purpose of pruning bearing fruit plants is as follows:

- To thin overcrowded growth to permit more efficient spraying and to allow better light penetration/interception and air circulation through the plant

- To remove dead, diseased, weak-growing, or unproductive wood

- To limit the height and spread of the plant

- To stimulate the growth of new fruit-bearing wood for next year’s crop

- To properly direct the growth of new shoots throughout the plant and to maintain good balance in the tree structure

- To perform some fruit thinning by thinning out of fruiting wood, as is usually practiced with peaches

Bearing Habits of Fruit Crops

Understanding the bearing habits of fruit trees is important for proper pruning. Without this knowledge, a grower may destroy a major portion of the fruit buds and potential crop when pruning. Fruit plants grown in Alabama produce their flowers from a simple bud (flowers only) or a mixed bud (containing flower parts and vegetative growth). The position of fruit buds on the plant also varies and influences pruning.

Peaches produce their fruits from simple buds positioned laterally along 1-year-old shoots. Peach buds for the current crop were produced on wood that grew during the previous year’s summer. The same is true for plums and cherries, but an even larger part of the crop is produced from mixed buds formed on spurs 2 years old and older. Therefore, when you prune, thin out a portion of the 1-year-old fruiting wood but leave as much of this wood as desired for this year’s crop. Some renewal pruning of spurs on plums and cherries is necessary as trees age.

Apples and pears produce fruit from mixed buds. Usually, these buds are located terminally on 1-year-old shoots and fruiting spurs, but occasionally, fruit buds develop in lateral positions on 1-year-old shoots. ‘Gala’ and some of the more recently introduced varieties seem to have a strong affinity for developing fruit buds in lateral positions on 1-year-old wood.

Fruit buds of persimmons and figs are mixed buds and are located laterally on 1-year-old growth. Most of these plants produce their fruits on current spring growth, developing only from 1-year-old wood. Thus, it is important that the cultural program used results in an abundance of healthy 1-year-old shoot growth.

Citrus plants, such as satsuma mandarin, produce simple (flower) and mixed buds on the previous season’s growth. Mixed buds produce new shoots that have fruit buds in the axils of new leaves. This is commonly referred to as leafy bloom. (Bouquet bloom is formed from simple flower buds.) Annual pruning is not needed until plants begin crowding, except for removing dead or diseased wood. Removal of water sprout growth on the insides of trees will become necessary in older trees.

Time of Pruning

The pruning time varies with the plant type and its fruiting habits. Although apples, pears, and figs can be pruned during winter, waiting until February and March is preferable. Peaches, nectarines, and plums should not be pruned from October through January. Prune these during February and March, preferably before early bloom. However, pruning may extend through the flowering season with no detrimental effects. Water sprouts (upright, sucker-type growth) can be removed during spring and summer. Removing additional excess growth inside peach and nectarine trees from 3 to 6 weeks ahead of harvest of mid- and late-season varieties can be helpful. This reduces rot problems and enhances the development of desirable fruitwood.

Apples should be pruned in late winter before bloom development. However, dwarf trees on a trellis and larger semidwarf trees may also be summer pruned during July and August.

In trellised and other high-density apple plantings, summer pruning of current season shoots 2½ to 5 weeks ahead of harvest is beneficial. Current-season growth, especially in the upper portions of trees, is headed back to 2 to 8 inches, depending upon the need for branches or new spur wood. If growth is very excessive, some shoots are completely removed. Removing current-season growth opens trees for easier pest management, greatly enhances fruit color, and makes harvest easier. This practice is especially valuable in older, mature plantings. Fruiting spurs will be found growing from wood that is 2 years old and older. When you prune, leave the short and medium-length shoots that grew last year and keep the healthy, vigorous fruiting spurs. This is particularly important with spur-type apples.

Pruning Apples and Pears

- Remove dead, diseased, weak, and unproductive wood.

- Keep the center of the tree along the trunk open to permit spray materials and light to penetrate the tree better.

- When necessary, cut large limbs back to a side branch to control the height and diameter of limb spread.

- Thin out thick growth to encourage good, vigorous leaf development early in the season, with only moderate growth during June and July for fruit bud development.

- Between July 15 and August 1, cut back new growth not needed for branches to two or three buds if apple trees are on dwarf rootstock and trellised. Cutting back new growth will promote the formation of fruiting spurs and allow full light exposure for better fruit color.

- Remove stubs when pruning unless cuts are being made for spur development. However, never cut into the collar of a branch near its point of attachment to the trunk. This will involve leaving a very short stub when a branch is removed. Cut back to a lateral branch going in the direction you want the plant to grow.

- Prune European pears just enough to control growth and remove interfering wood. This will help prevent fire blight.

- Asian pears require annual pruning, similar to apples and pears, depending on which training system (leader, modified leader, or open center) is used. To reduce fire blight, avoid excessive pruning. Do not allow fruiting spurs to develop on the trunk, and keep height down by cutting the main leader and/or scaffold leaders to a secondary branch annually.

Pruning Peaches, Nectarines, and Plums

- Remove dead, diseased, and weak wood, interfering branches, and trunk suckers.

- Keep the center of the tree open by cutting back to a branch growing outward. Remove upright growth unless needed to fill in a blank space (figure 9). During the spring, remove or rub off sprouts arising on the top sides of major scaffolds on the interior part of a tree near the trunk.

- Keep trees within bounds by cutting the main scaffold branches back to a lateral growing in the same general direction as the scaffold branches. Maintain tree height at 7 to 8 feet by topping upper branches to an outward-growing branch where possible. If you want taller trees that must be worked with ladders, top branches at a height of about 10 feet.

- Balance pruning and fertility to maintain a good supply of annual growth, 18 to 24 inches long, for the next year’s crop.

- Remove at least half the fruiting wood throughout the tree so that each fruiting branch occupies its own space without being crowded. This should involve removing some 2-year-old and 1-year-old wood. Examine fruit buds for damage before pruning. If freezing weather reduces crop potential, do not remove as much fruiting wood so that a maximum crop is possible. Immediately after harvest, complete a thorough pruning.

- Figure 9. Bearing peach tree before pruning.

- Figure 9. Same tree pruned. Note open center, heading back of branches, and plenty of fruiting wood.

Pruning Figs

- Thin out weak, dead, and diseased growth by cutting back to laterals.

- Keep the center of the plant open and reduce the height of laterals to 7 to 8 feet by pruning to secondary branches. A larger plant can be developed if you want to use ladders.

- Maintain a good supply of current growth, which produces the main crop of figs.

Chip East, Extension Agent; Elina Coneva, Extension Specialist, Professor; David Lawrence, Extension Agent; and Edgar Vinson, Assistant Extension Professor, all in Commercial Horticulture, Auburn University. Originally prepared by Paul Mask, former Assistant Director, Agriculture, Forestry, Wildlife, and Natural Resources; Arlie Powell, former Extension State Program Leader; William Dozier, Extension Specialist, Professor, Poultry Science; David Williams, former Extension Horticulturist; and David Himelrick, former Extension Horticulturist, all with Auburn University.

Chip East, Extension Agent; Elina Coneva, Extension Specialist, Professor; David Lawrence, Extension Agent; and Edgar Vinson, Assistant Extension Professor, all in Commercial Horticulture, Auburn University. Originally prepared by Paul Mask, former Assistant Director, Agriculture, Forestry, Wildlife, and Natural Resources; Arlie Powell, former Extension State Program Leader; William Dozier, Extension Specialist, Professor, Poultry Science; David Williams, former Extension Horticulturist; and David Himelrick, former Extension Horticulturist, all with Auburn University.

Revised September 2025, Fruit Culture in Alabama: Training & Pruning Fruit Trees, ANR-0053-K