Crop Production

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are emerging organic contaminants known as “forever chemicals” due to their widespread applications in domestic and industrial sectors. The ubiquitous presence of PFAS in soil and water environments is a threat to human and animal health. Proper monitoring of PFAS status in soil and water environments is essential for protecting human and animal health. Adopting appropriate strategies is important for mitigating the adverse impact of PFAS in cases of reported soil and water contamination.

What Is PFAS?

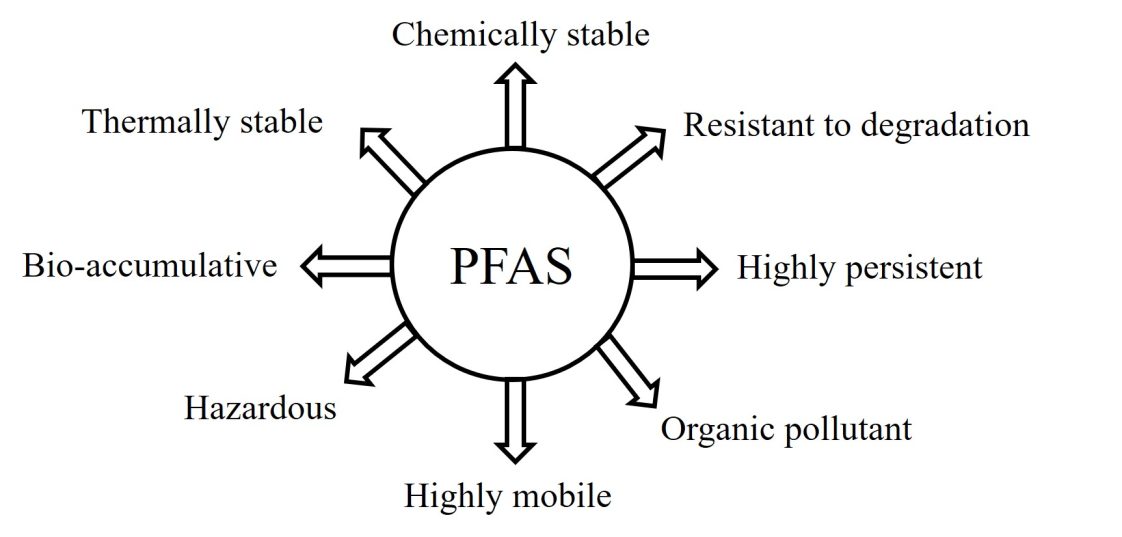

Figure 1. Important properties of PFAS in the environment

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are human-made organic compounds well known for their widespread uses in industrial sectors and everyday consumer products. Thousands of PFAS compounds have been produced since the 1940s on a commercial scale. They are used in the textile, food packaging, pharmaceutical, energy, automobile, electroplating, and chemical industries across the globe. PFAS molecules remain nonreactive and very stable over a wide range of temperatures (figure 1) because of their chemical structure. These properties make them beneficial substances for a broad range of industrial applications. Because of widespread applications, PFAS are considered forever chemicals and can be found in soil, water, and edible plant produce. High thermal and chemical stability make PFAS persistent and chemically stable in the environment, particularly in soil and water.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances have been reported in the blood samples of wildlife and people in the United States. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are bioaccumulative and mobile in the environment; these compounds seriously threaten human and animal health. Because of their ubiquitousness and adverse impact on animal and human health, PFAS have been recognized as an emerging contaminant by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). In recent years, there has been considerable attention given to researching PFAS in the water-soil-plant-human continuum to protect human and animal health.

Principal Sources of PFAS in the Environment

PFAS are not naturally occurring compounds in the environment but are introduced by human activities. Principal sources of PFAS in soil and water environments are as follows:

- Commercial products. Flame retardants, lubricants, stain repellents, food packaging materials, paints, cookware, and beauty products.

- Biosolids. Sewage-sludge and composts are sources of PFAS. Usually, biosolids contain a higher concentration of PFAS than composts. The magnitude of PFAS concentration in the compost depends on the raw materials used for composting. Contamination of groundwater and soils with PFAS following the application of biosolids and composts is quite common across the globe.

- Wastewater. Irrigation with wastewater is a chief human activity responsible for contaminating soil and water bodies with PFAS.

Exposure to PFAS and Their Potential Effects on Human Health

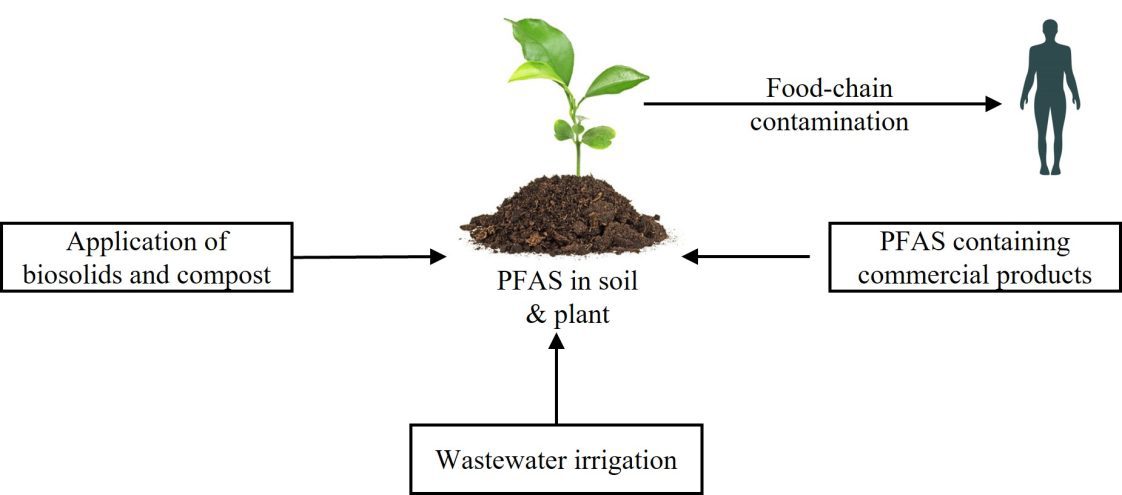

Figure 2. Possible mechanism of food-chain contamination with PFAS

Due to its persistent nature, PFAS is likely to contaminate the food chain and affect human health once it enters the environment, especially soil (figure 2). Drinking contaminated water, eating crops grown on soils contaminated with PFAS, and swallowing contaminated soil are among the major human exposure pathways. Beauty products and inhalation of house dust are other possible exposure pathways. Common human health issues due to ingestion of PFAS include cancer, liver diseases, high cholesterol, reproductive system damage, and thyroid disorders.

Allowable PFAS Concentration in Water and Legislation

The USEPA issued nonregulatory health advisories for two PFAS substances, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), on the possible human health effects due to lifetime exposure from drinking water. The health advisories suggest that combined concentrations of PFOA and PFOS at 70 parts per trillion (0.07 μg/L) are permissible over lifetime exposure from drinking water. The PFOA and PFOS are the most observed PFAS contaminants in drinking water in the United States. The USEPA has not yet established regulatory standards for any PFAS in drinking water. However, various state departments, particularly those of Michigan, Vermont, and New Jersey, have established guidelines for the maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for various PFAS compounds in drinking water (table 1).

Table 1. Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for PFAS in Drinking Water in Different Regions of the United States

| Region | Specific PFAS | Established MCLs (ng/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Michigan | Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) | 6 |

| Michigan | Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) | 8 |

| Michigan | Perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) | 400,000 |

| Michigan | Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) | 16 |

| Michigan | Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS) | 51 |

| Michigan | Perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS) | 420 |

| Michigan | Hexafluoropropylene oxide-dimer acid (HFPO-DA) | 370 |

| Vermont | Sum of PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, and perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA) | 20 |

| New Jersey | Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) | 14 |

| New Jersey | Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) | 13 |

| New Jersey | Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) | 13 |

Reported PFAS Levels in US Soil, Water, Plants, Biosolids, and Composts

Given the widespread occurrence of PFAS and associated potential human health effects, understanding PFAS status in various potential sources, particularly, soil, water, plants, biosolids, and composts, is crucial for possible mitigation strategies. Research efforts have been made to determine the status of PFAS in the soil and water resources in the United States (table 2).

Table 2. Reported PFAS Levels in Soil, Water, Plants, Biosolids, and Composts in the United States

| Source | PFAS Content | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Soils | The mean concentration of perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids in surface soils near fluoropolymer industry was 150 ng g-1. | Ohio |

| Municipal biosolid amended soils | PFOS: 1.6(±1.7) μg/kg (for ≤44,813 kg biosolids/ha); 4.1 (±1.9) μg/kg (for >110,688 kg biosolids/ha) PFOA: 0.32 (±0.33) μg/kg (for ≤44,813 kg biosolids/ha); 0.84 (±0.48) μg/kg (for >110,688 kg biosolids/ha) | Arizona |

| Riverine water | Mean concentration of PFAS in the water samples of Alabama, Coosa, and Chattahoochee Rivers were 100, 191, and 28.8 ng L-1, respectively. | Alabama |

| Estuarine water | Sum of PFAS ranged from 4.48 to 25.08 ng L-1. | Coastal Alabama |

| Groundwater | PFOA: 149.2–6410 ng L-1 PFOS: 12–150.6 ng L-1 PFHxS: 12.7–87.5 ng L-1 PFBA: 10.4–1260 ng L-1 PFHxA: 9.7–3970 ng L-1 | Decatur, Alabama |

| Biosolids | PFOS: 403 ± 127 ng g-1 PFOA: 34 ± 22 ng g-1 Perfluorodecanoate (PFDA): 26 ± 20 ng g-1 | Biosolids were collected from 32 states in the United States. |

| Sewage-sludge | PFOA: ≤320 ng g-1 PFOS: ≤410 ng g-1 PFDA: ≤990 ng g-1 Perfluorododecanoic acid (PFDDA): ≤530 ng g-1 | Decatur, Alabama |

| Solid-waste compost | PFOA + PFOS: 7.94-11.5 μg kg-1 | Composts were collected from Washington, Oregon, California, Massachusetts, and North Carolina. |

| Crop plants | In lettuce: PFBA: up to 266 ng g-1; Perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA): up to 236 ng g-1 In tomato: PFBA: up to 56 ng g-1; PFPeA: up to 211 ng g-1 | Midwestern United States |

| Grass | PFOA: 10–200 ng g-1 PFOS: 1–20 ng g-1 PFDA: 3–170 ng g-1 | Decatur, Alabama |

Remediation Options to Treat PFAS

- Remediation of PFAS-contaminated soil may be achieved by mobilizing PFAS in soil and subsequently removing them through phytoremediation (using plants) or by immobilizing PFAS in soil through sorbent materials.

- Immobilization techniques that reduce PFAS mobility and bioavailability in soil, thereby decreasing their uptake by plants and leaching to groundwater, are more practical.

- Various sorbent materials, namely activated carbon and biochar, are effective in immobilizing PFAS in contaminated soils.

- The use of activated carbon, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis are useful technologies for the removal of PFAS from water.

Conclusions

- The complexity of the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and their persistent nature make the remediation of PFAS challenging in both the solid and aqueous mediums. Therefore, the following should be considered to avoid food chain contamination and associated health risks due to PFAS.

- The disposal of biosolids, composts, and biowaste products through land application is of great concern. Assessment of PFAS status in biosolids is important before application into agricultural fields.

- It is essential to regularly monitor the PFAS levels in the soil-plant system of agricultural fields that have been receiving biosolids for an extended period to prevent PFAS contamination in the food chain.

- In case of PFAS buildup in agricultural soils and groundwater, appropriate mitigation strategies must be adopted to protect the water-soil-plant-human continuum from PFAS.

Literature Followed

EPA (2016). Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). EPA 822-R-16-003.

MPART (2020). Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for PFAS compounds, Michigan PFAS Action Response Team.

ANR (2019). PFAS in drinking water, Drinking Water & Groundwater Protection Division, Agency of Natural Resources, Department of Environmental Conservation, Government of Vermont.

NJDEP (2020). NJDEP Drinking Water Standards, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, New Jersey.

Zhu, H. and Kannan, K. (2019). Distribution and partitioning of perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids in surface soil, plants, and earthworms at a contaminated site. Science of the Total Environment, 647: 954-961.

Pepper, I. L., Brusseau, M. L., Prevatt, F. J. and Escobar, B. A. (2021). Incidence of Pfas in soil following long-term application of class B biosolids. Science of The Total Environment, 793: 148449.

Viticoski, R. L., Wang, D., Feltman, M. A., Mulabagal, V., Rogers, S. R., Blersch, D. M. and Hayworth, J. S. (2022). Spatial distribution and mass transport of Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in surface water: A statewide evaluation of PFAS occurrence and fate in Alabama. Science of The Total Environment, 836: 155524.

Mulabagal, V., Liu, L., Qi, J., Wilson, C. and Hayworth, J. S. (2018). A rapid UHPLC-MS/MS method for simultaneous quantitation of 23 perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in estuarine water. Talanta, 190: 95-102.

Lindstrom, A.B., Strynar, M.J., Delinsky, A.D., Nakayama, S.F., McMillan, L., Libelo, E.L., Neill, M. and Thomas, L. (2011). Application of WWTP biosolids and resulting perfluorinated compound contamination of surface and well water in Decatur, Alabama, USA. Environmental science & technology, 45(19): 8015-8021.

Venkatesan, A. K. and Halden, R. U. (2013). National inventory of perfluoroalkyl substances in archived US biosolids from the 2001 EPA National Sewage Sludge Survey. Journal of hazardous materials, 252: 413-418.

Washington, J. W., Yoo, H., Ellington, J. J., Jenkins, T. M. and Libelo, E. L. (2010). Concentrations, distribution, and persistence of perfluoroalkylates in sludge-applied soils near Decatur, Alabama, USA. Environmental science & technology, 44(22): 8390-8396.

Choi, Y. J., Kim Lazcano, R., Yousefi, P., Trim, H. and Lee, L. S. (2019). Perfluoroalkyl acid characterization in US municipal organic solid waste composts. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 6(6): 372-377.

Blaine, A. C., Rich, C. D., Hundal, L. S., Lau, C., Mills, M. A., Harris, K. M. and Higgins, C. P. (2013). Uptake of perfluoroalkyl acids into edible crops via land applied biosolids: field and greenhouse studies. Environmental science & technology, 47(24): 14062-14069.

Yoo, H., Washington, J. W., Jenkins, T. M., and Ellington, J. J. (2011). Quantitative determination of perfluorochemicals and fluorotelomer alcohols in plants from biosolid-amended fields using LC/MS/MS and GC/MS. Environmental science & technology, 45(19): 7985-7990.

Prasenjit Ray, Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences; Debolina Chakraborty, Research Assistant Professor, Department of Biosystems Engineering; and Rishi Prasad, Associate Professor and Extension Specialist, Department of Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences, all with Auburn University

Prasenjit Ray, Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences; Debolina Chakraborty, Research Assistant Professor, Department of Biosystems Engineering; and Rishi Prasad, Associate Professor and Extension Specialist, Department of Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences, all with Auburn University

New July 2024, Per- & Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Environment: Sources, Health Effects & Remediation Options, ANR-3090