Fire

When using prescribed fire in longleaf pine stands, land managers should consider using more frequent growing season fires. Following is a summary of the benefits of this management strategy.

Prescribed fire is an effective and important tool for anyone managing forest land, but it is especially important in longleaf pine stands. Historically, longleaf pine was maintained by periodic, low intensity fires. These fires started either by lightning strikes during the growing season or by Native Americans ignition.

Longleaf pine has characteristics during each stage of its life cycle that make it specially adapted to periodic fires. For example, fire clears away understory brush and debris so longleaf seed can make contact with bare mineral soil needed for better germination. Longleaf pine seedlings then have a unique “grass stage” characterized by limited height growth and the development of long needles that protect the thick bud from potential fire damage. After leaving the grass stage, longleaf undergo rapid height growth that helps get the terminal bud above any future fires. Finally, mature trees have thick bark that protects the cambium from fire damage.

In the early 1900s, cultural shifts caused policymakers to call for the suppression of all fires, both natural and man-made. At that time, starting any kind of fire was thought of as a malicious, harmful act. However, this lack of fire contributed, in part, to the loss of longleaf pine forests that were eventually replaced with other less fire-tolerant forest communities, such as slash pine, loblolly pine, and various hardwoods such as sweetgum, beech, and red maple.

Modern research has shown that prescribed fires are a vital part of longleaf management. Prescribed fires can reduce competition and increase desirable understory grasses and forbs that benefit numerous wildlife species. As forest owners seek to manage their forests for timber, aesthetics, recreation, and wildlife, prescribed fire can be a cost-effective way of reaching those goals.

However, just burning the forest is not good enough. Landowners and land managers should think about seasonal timing of prescribed fire and burning frequency, both of which can influence forest understory composition and tree growth

Comparison of Seasonal Timing

Dormant-Season Fires (December to March)

Burning longleaf stands during the winter is common across the southeastern United States. Prescribed fires during the dormant season can produce what is considered a cooler fire, which may appeal to landowners who are uncomfortable with fire. As with any land management tool, there are benefits and drawbacks to the approach.

Benefits of Dormant-Season Fires

Typically, more days are available to burn in the dormant season because of cooler and usually wetter conditions. During this time of year, the passage of cold fronts is often followed by winds that are more predictable and steady, making for more predictable day-of-burn conditions.

Dormant-season fires are an excellent approach for landowners reclaiming longleaf stands that have not been burned in several years. There is often a deep layer of needles and leaves that can serve as fuel and burn very hot. Cooler air temperatures in the dormant season help limit damage to trees.

Dormant-season fires can be useful in longleaf pine stands that have been recently regenerated either by natural or artificial means. Fire is necessary for longleaf pines, even during the seedling stage. Cooler air temperatures often result in less damage to the buds of seedlings.

Drawbacks to Dormant-Season Fires

Dormant-season fires produce fewer forbs and grasses than do growing-season fires. These fires also have less of an effect on hardwood competition. Winter fires will top-kill undesirable hardwoods, such as sweetgum and water oak, but they will quickly resprout during the following growing season.

So called slow-moving fires can also be detrimental to older trees when it has been several years without fire. In some cases, the fire may move so slowly that heat and flames can remain at the base of a tree too long, damaging the cambium or killing tree roots that have moved into the more favorable conditions around the tree base. This can weaken the older trees, leading to tree death months or even years after the prescribed fire was conducted.

Growing-Season Fires (April to July)

Growing-season fires are what longleaf stands are naturally adapted to and what forest owners should attempt to replicate when possible. The southeastern United States is prone to spring and summer thunderstorms that produce lightning, which can ignite fires that naturally maintain longleaf forests. In today’s landscapes, however, these fires are suppressed by human intervention—roads, cities, and fields that fragment the land. As with dormant-season fires, benefits and drawbacks must be considered.

Benefits of Growing-Season Fires

Growing-season fires do a better job of suppressing woody competition including low shrubs and undesirable tree species, such as water oak, red maple, and sweetgum. Because plants are actively growing during this time, they have limited energy reserves in their roots, making it difficult for them to resprout.

Growing-season fires encourage growth and diversity of native grasses. Without these fires, many native grasses will not put on a seed head, thereby limiting their regeneration and spread. Bunchgrasses, such as bluestem and wiregrass, are an important component of the longleaf ecosystem, as they provide habitat for many species of wildlife. Native forbs will grow among bunchgrasses and provide food and habitat for many wildlife species, such as white-tailed deer, bobwhite quail, gopher tortoises, and wild turkey.

Growing-season fires are vital to prepare for natural regeneration of longleaf pine. Longleaf seeds generally drop in October and November, and they need bare mineral soil for better survival. A proper seedbed can be prepared using a timely growing-season fire to remove understory vegetation and thick layers of litter.

Drawbacks to Growing-Season Fire

Check with your state forestry commission or forest service to find out whether prescribed burning is permitted in the growing season. Due to air quality concerns in some states and around urban areas, burn permits can be difficult to obtain in the growing season

Weather also can limit application of a growing-season fire. Factors such as wind, humidity levels, drought, and temperature all affect fire behavior. During the growing season, these can be somewhat less predictable or conducive to optimal burning conditions.

Comparison of Fire Frequency

Fire frequency plays an important role in creating a landowner’s desired forest structure and wildlife habitat. If the goal, for example, is maintaining a savanna-type ecosystem for certain wildlife species, stands may need to be burned every 1 or 2 years. The same is true when preparing a site for natural regeneration.

To illustrate the impact of fire frequency, we will compare photos of longleaf pine forests managed long-term using dormant-season fires and growing-season fires on 2-, 3-, and 5-year intervals. The stands featured are located on the Escambia Experimental Forest near Brewton, Alabama. They were part of the 1969 seed crop and were naturally regenerated.

Two-Year Fire Interval (Figures 1 and 2)

When you initially compare the images of the 2-year fire, you see that both forests have a fairly open understory. Closer examination, however, reveals important differences.

Notice that the understory of the dormant-season fire has a lot of pine straw on the ground (fig. 1). That litter layer can prevent successful natural regeneration. On the left side of the image is a sweetgum sapling, which is an indication that hardwoods are not being successfully controlled by these fires. This can become a problem long-term for landowners who are trying to manage longleaf pine. Eventually, these saplings will grow and develop thick bark, making them more tolerant of fire. They will continue to grow and take up space in the stand.

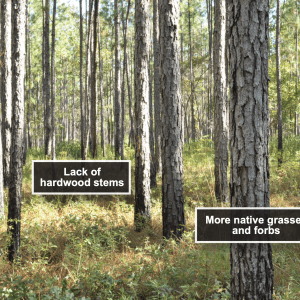

By comparison, the understory of the growing-season fire has few hardwood saplings (fig. 2). Also of note are the understory grasses, which are visible in the lower portion of the image. These grasses are promoted by growing-season fire and are not present in the dormant-season fire.

- Figure 1. Longleaf pine stand burned every 2 years in the dormant season.

- Figure 2. Longleaf pine stand burned every 2 years in the growing season.

Three-Year Fire Interval (Figures 3 and 4)

Longleaf pine stands burned every 3 years have a relatively open understory. In general, the woody material is 2 to 3 feet taller than in the stands burned every 2 years.

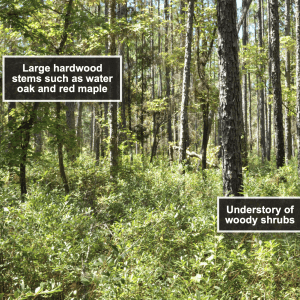

In the image of the dormant-season fire (fig. 3), notice that hardwood trees, such as water oak and red maple, have become fire resistant and are present in the midstory. Understory plants, such as gallberry and beautyberry, are approaching 4 feet in height in some areas. As the number of hardwoods and woody-stemmed understory plants increases, so does the difficulty in burning. Hardwood leaves and woody stems take much more heat to ignite and burn than do pine straw and small vegetation.

In the stand burned in the growing season (fig. 4), notice the few hardwoods present in the midstory and the bunchgrasses in the foreground. Patches of open ground also are visible.

- Figure 3. Longleaf pine stand burned every 3 years in the dormant season.

- Figure 4. Longleaf pine stand burned every 3 years in the growing season.

Five-Year Fire Interval (Figures 5 and 6)

Introducing fire into a longleaf stand after a long interval can cause problems due to fuel buildup. This buildup can cause unpredictable fires, possibly posing danger to fire crews and nearby property.

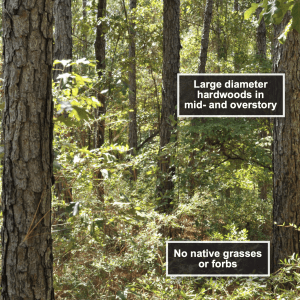

The stand burned every 5 years in the dormant season shows hardwood trees, such as water oak, red oak, dogwood, and blackgum, present in the mid-and overstories (fig. 5). In some cases, the hardwood trees have reached diameters of 6 inches and larger at 4. feet above ground level and are almost completely resistant to fire. The understory litter layer is thick with leaves and pine straw, making natural regeneration unlikely. No native grasses are present.

In contrast, the stand burned in the growing season has a much more open understory. Bare ground is still visible in spots, but the litter layer is thick with pine straw. Notice the larger clump of vegetation on the right side of the image (fig. 6). This is probably an area where fire did not effectively control the vegetation in the prescribed fire, possibly due to a downed log or other debris that prevented the fire from getting into the small area. This is particularly concerning because it will be another 5 years before the next fire. Over time, this area will continue to increase in size as the vegetation becomes larger and more fire resistant. Areas like this become islands of vegetation, and fire will no longer be an effective tool for management and control.

- Figure 5. Longleaf pine stand burned every 5 years in the dormant season.

- Figure 6. Longleaf pine stand burned every 5 years in the growing season.

Summary

Land managers often opt to burn stands every 2 or 3 years during the dormant season. However, dormant-season fires can lead to a decrease in native plants and an increase in unwanted hardwoods. Fire frequency and seasonality should be based on current forest conditions and landowner goals.

In cases when landowners are unable to obtain a permit for a growing-season fire, it is better to conduct a dormant-season fire than not to burn at all. Allow no more than 3 years between prescribed fires in longleaf stands.

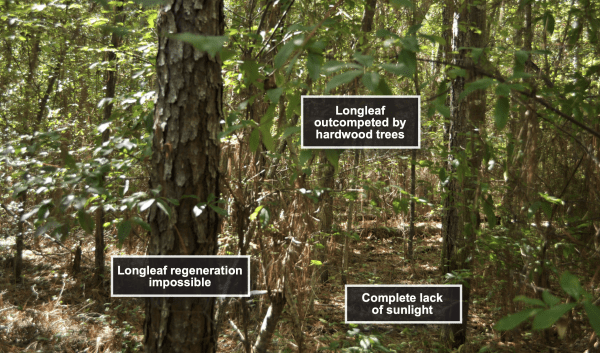

A stand that has not been burned for a very long time will need mechanical or chemical preparatory work before a fire is beneficial. Eventually, a longleaf pine forest that is not burned will no longer be a longleaf pine forest due to encroachment of undesirable hardwoods and the loss of native understory vegetation (fig. 7).

Figure 7. Longleaf pine forest that has not been burned in more than 30 years.

Prescribed fire is easily one of the most effective and affordable tools for managing longleaf forests. Before burning, be sure to have specific goals in mind, create a burn plan, get a permit from your local forestry commission office, and work with a certified burn manager.